No question about it, factory team bikes have a hard life but their prototype predecessors have an even harder one. CDB checks out a 1970 370RN Suzuki development model.

Words and pics Tim Britton

Looking at the machine it was obvious the Japanese company had come to play seriously in this off-road lark and clear too was Pettersson’s influence.

Now, as we discussed this bike the level of commitment to its build emerged, as it started from an engine and a few parts.

“I’ve no idea what happened to the rest of the bike,” says owner Clive Bussey, as he listed what few parts he started with. “I’d love to find out but typical of those days, once the team were finished with one season’s machines, they were often broken up.”

The engine arrived with Clive about 15 years ago, along with some rear dampers, a front wheel and the right-hand fork leg, plus the unusual bottom fork yoke and a few other bits and bobs.

“It went into the workshop and stayed there until I met up with Olle Pettersson and showed him what I had. He studied it, told me it was definitely one of the three engines built for him, Robert and Geboers – he also told me it was definitely not his engine.”

Unlike the two Belgians, Pettersson always used a right-hand gear change.

“He was asking a few seemingly odd questions,” says Clive, “after I answered them he explained if the engine had been used as a right-hand change then there would be marks here and here,” – Clive points to the casings – “but there were none so this engine is that of either Geboers or Robert.”

During his visit with Pettersson, two things happened which made the project leap forward from a ‘…nice idea if…’ to ‘…okay, it’s feasible now…’ Pettersson had a genuine sandcast carburettor from that period.

“It was the correct 36mm one which all three bikes had and while not vital to make the bike work as a modern carb would fit, it is absolutely vital for the period look I was after.”

Suddenly things were looking up but Pettersson disappeared for a few moments and came back with some studio photoshoot images of his bike in 1970. These were side-on, or landscape, detailed pictures and showed everything Clive needed.

“When I got home it was a relatively simple job to blow the pics up so they were full size and from there I could work out what I needed to make the missing bits.”

Armed with these images and now possessing a carburettor too, Clive set to and re-created what was missing.

The biggest part of the bike to create has to have been the frame.

With the image available and a scaled-up drawing of the frame now possible, the lad needed some steel tube and of all things this proved to be the biggest hurdle.

Despite the fact the 370RN is a works bike it is actually a prototype and as such doesn’t have a lot of fancy stuff on it, all of that came in later models and the frame is seamless mild steel tube rather than some form of exotica weighing as much as a drink of water.

While the scaled-up drawing could show what outside diameter the tubing should be, it couldn’t show or give a clue to the gauge it is.

Luckily, Clive has another, later frame and with Pettersson confirming the same mild steel was used for several years felt confident of assuming the gauge would be the same. However, finding the stuff was a different matter.

“In the end I’d almost given up hope then happened on a steel stockist who thought he might have the right gauge and diameters, went to check and came back saying he had and if I’d not called he was just about to scrap it as it’s obsolete.

“When I heard that I bought the lot just in case.” After that it was a relatively simple task to bend the tube to shape and weld it up.

“I forgot to say, the swinging arm came with the parts I had, it is a bit different as it’s aluminium. It wasn’t that successful and the team went back to steel swinging arms quite quickly.”

With the frame made and the swinging arm in and the suspension units fitted, other bits could be hung in place. Already with the pile of parts was the massive but hollow casting used for the bottom yoke.

This casting technique leaves a strong but light structure which adds lightness without sacrificing strength.

Once this was in place, the top yoke could be measured up and a pattern made so it could be sandcast then machined by Clive to the required size.

To digress slightly for a moment, the sand casting technique is ideal for low volume work, being a fairly quick process allowing changes to be made, but as the mould has to be remade each time it’s not ideal for production work, but for three bikes expected to be modified frequently it is probably the best way to produce parts.

Though most of the sandcast parts in this feature are in aluminium or magnesium alloys, other metals can be cast too.

In case you didn’t know, a pattern is made slightly bigger than the required size to cope with shrinkage on cooling, sand is packed round the pattern, the pattern removed and molten metal poured in.

The mould is then broken when sufficient time has passed for the metal to solidify.

Obviously that’s condensed the technique a fair bit but it is the basics. Right, top yoke cast and machined, bottom yoke in place, time for the fork legs.

Obviously the Suzuki has two fork legs, one came with the bike and was for the right-hand side but the left-hand side one was missing.

Still that’s not a major task to solve if you’ve just made a frame as forks are basically just one tube sliding inside another with some clever damping valving inside to control the oil flow.

So with one available as a pattern the missing one was soon created from steel tube for the stanchion and alloy billet for the slider. It just required careful machining…

For the first build the front wheel was left as it was while a production RM rear hub was modified slightly to match the original.

It is probable the production hub was patterned after the prototype so this is a bit of reverse engineering.

Whatever the reason, the RM hub is magnesium and the original brake plate fitted straight in so now Clive had a rolling chassis with ultra rare Dunlop sports tyres fitted to the Akront flanged rims.

The engine department

It is actually surprising how basic this ex-works motor is, it breathes through a normal type of carburettor, has four gears and is on points ignition while the production bikes got electronic sparks.

Aluminium alloy is used for the main castings but magnesium alloy for the flywheel and clutch cases.

When the engine was stripped the reason for the motor to be sidelined was apparent, second gear was broken.

Investigation showed the kick-start cog tab had sheared off, dropped in to the pair of gears and done all sorts of nasty things to the cogs, to the point where they were unusable.

Some inspection and testing found the cause of the problem to be that the kick-start cog had been hardened all the way through rather than just case hardened.

Clive made a new one, a stronger one and had it hardened properly.

The gears were a different matter but Nova Racing Transmissions Ltd made a pair using what was left of the originals as a pattern.

When things drop in the gearbox the crank case castings can easily burst but Mr Bussey checked these very closely and they’re in excellent condition.

Inside the cases the mechanicals are apparently impressive with much bigger gears compared to say a contemporary Greeves or Maico and the rotary drum shifter is distinctly modern.

All that remained, once the engine’s ailments were cured, was to reassemble it and slip it into the frame.

Progressing faster

Once the engine is in the frame and the bike can roll on its own wheels, things start to happen faster as there is an end in sight.

Some alloy sheet was cut and became an airbox, more was used to make the fuel tank.

“I made a former out of resin to match the tank in the picture Olle Petersson gave me, then beat out the alloy myself. This is just as the race shop would have done in those days but later bikes had the tanks stamped out.”

Making the tank wasn’t that difficult, the time consuming bit was making press tools to form the filler neck and fuel tap depression.

More aluminium sheet was used for the seat base and it was upholstered to the correct shape by a craftsman Clive knows.

One of the many eye-catching features of the Suzuki is its exhaust system and that again is made in the Bussey workshop from steel sheet, rolled out to size and welded up.

It seems the original works Suzuki exhausts – be they MX or racing – were made by an elderly Japanese couple in their house.

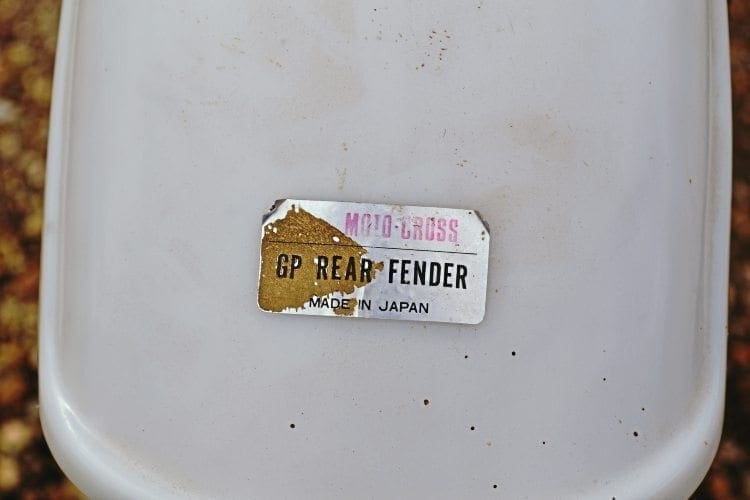

Okay, so now it’s looking like a bike, the mudguards came from some other parts Clive acquired but are correct for the period and match the studio shots of the bike from years ago.

Likewise the handlebars and levers were already available to Clive and fitted straight on.

With everything assembled and working, the next stage was to make it look nice but not too nice.

There are a few parts such as the ’bars which show the patina of age and they’re staying that way too.

But certain things have to be refinished, magnesium for instance as it oxidises very quickly and is generally dipped in a chromate tank to produce the nice satin black colour.

Chromating is a nasty process with some evil chemicals but it does the job and its users are regulated.

Steel too oxidises, or rusts if you prefer, without a coat of something or other. Clive found a stove enameller close to his place and the shiny black enamel was soon on.

“I got some yellow cellulose paint matched to the pictures of the bike and sprayed that myself,” he tells me.

As the pair of us chatted about MX, scrambling and the period this bike was from in general, Clive added he’d saved some fasteners, made a few more, rescued a cable or two and rebuilt the wheels himself which all adds to the ownership of such a machine.

As we wound up, Clive did say despite having made loads of the parts to original spec he’d love to know if things like the original frame were still out there as for such a machine as this, original is better.

That said I reckoned he’d done a brilliant job and it looked spot on.

Olle Pettersson

In the Sixties, Swede Olle Pettersson was one of the top 250 MXers around. Riding for Husqvarna, he was Sweden’s national champion and also among the top world-class riders. However, the scene was changing and support wasn’t easy to find, Husqvarna offered a bike and some back-up but Suzuki came along and offered a contract… Pettersson was about to make history.

Look out for a forthcoming people feature on Olle by our Swedish contributor Birger Tommoss.

What was there

…and what was not. It is difficult enough for most of us to sort out a bike with a few bits missing but Clive Bussey had a mammoth task ahead.

Available: Engine, rear dampers, one fork leg, bottom yoke, front wheel, brake plates and shoes, alloy swinging arm.

To be made: Frame, rear hub, tank, seat, left-hand fork leg, air box, exhaust, fasteners, spacers.