The triple-cylinder Trident was badly timed in 1968, but what’s it like nowadays? We take a good look.

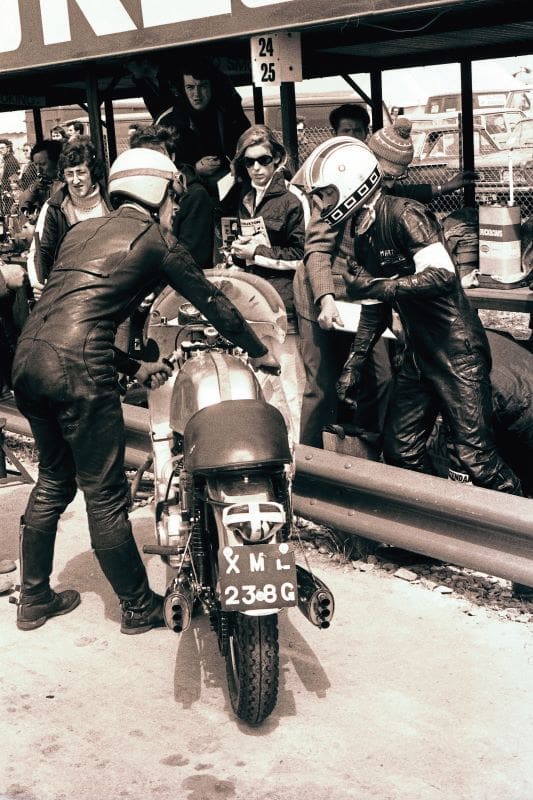

Words by Oli Hulme Photos by Matt (with great thanks to Hutch for riding his T150V past me for photos and letting me ride it! HTE motorcycles, Norfolk: 01328 700711)

Doug Hele had been nagging at me for years to give consideration to a three-cylinder engine design for larger capacity units. One evening late in 1963, after everyone had gone home, we sat in his office and, to amuse ourselves, we laid out the basic outline of what later became the 750cc three-cylinder Trident. This drawing was filed away as a memento.

– Bert Hopwood, in Whatever happened to the British Motorcycle Industry

For anyone with historical interest in the collapse of the British motorcycle industry, Bert Hopwood’s book is essential reading, if occasionally light on accurate dates. It seems the engine was originally designed on paper in early 1963. The TR3OC has produced an example of a prototype triple, one of a few P1 models built in the Triumph Experimental shop in 1964, which is now on display at the Triumph Visitor Experience at Hinckley.

This had a three-cylinder engine bolted into a modified 650 Bonneville Frame, with Bonneville running gear. Hopwood says that this first triple could have gone into production in 1965, as a stop-gap model to capture the big bike market while the designers got on with building something more modern, but the project was quietly pushed into a corner as it upset corporate politics.

Hopwood then refers to an undated meeting in 1966, in which the bombshell that Honda was working on a 750 four was dropped by a sales executive, and the triple concept was swiftly pulled out of the shadows. Suddenly, the triple was back on the table.

Things looked promising until the managers at BSA decided they wanted a triple to sell too, which had to be the same, but different. The BSA version needed to have an engine that sloped forwards and had a look similar to the ‘Power Egg’ twins, and it needed a different frame too, following BSA design principles. And then the original idea of a bike that looked like a Bonneville with three cylinders was dropped in favour of a new, sharp-sided look from Ogle Design, which took 18 months to complete and meant the bikes that should have shaken the world in 1965 were fatally late to the market. Hopwood describes it as being “minced about” and “designed by a committee”.

Once the first pre-production bikes were finished, eight were sent to the US for extensive testing and, one suspects, to reassure dealers that BSA-Triumph was going to come up with something new for them.

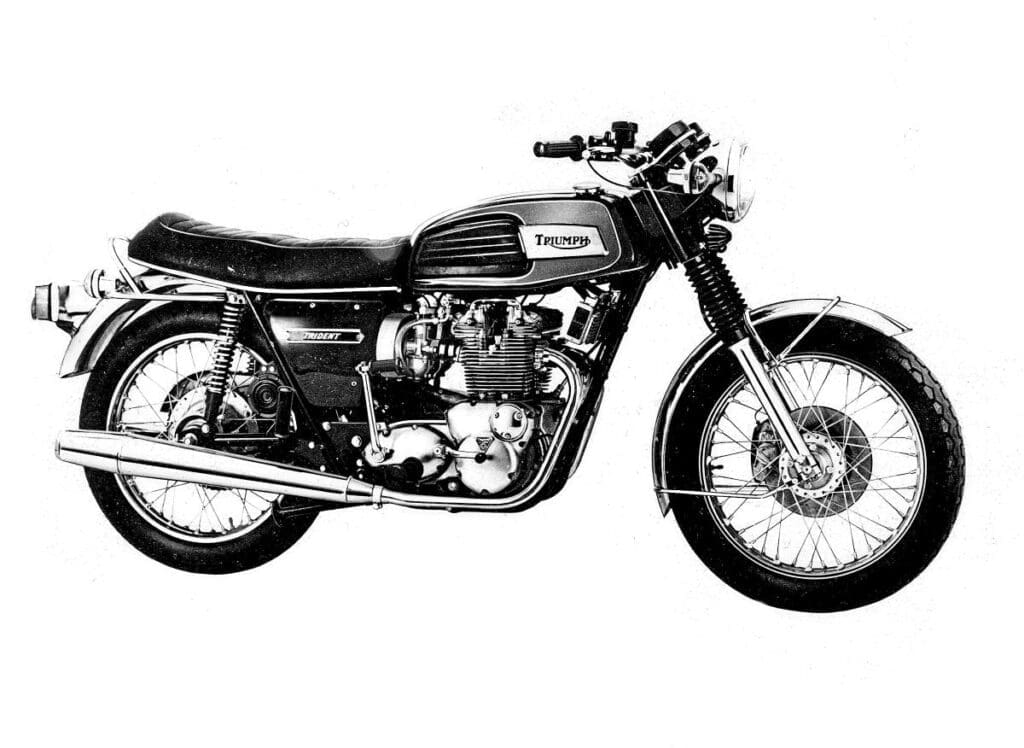

The production Trident finally arrived in 1968. It is interesting that today, bringing a bike from concept to production in two years seems quite rapid. Most manufacturers seem to spend that long designing an auxiliary USB port. But the rapid pace of development in the late 1960s meant the bikes were almost out of date as soon as they arrived. The first Trident came with a squared-off tank, kneepads, chrome panels and an exotic exhaust system, with three mini ray-gun pipes on either side, but at the same time they had to add extra bracing for the silencers. The bike used a Bonneville seat, the old Triumph twin leading shoe drum front brake, and a front mudguard that didn’t fit properly.

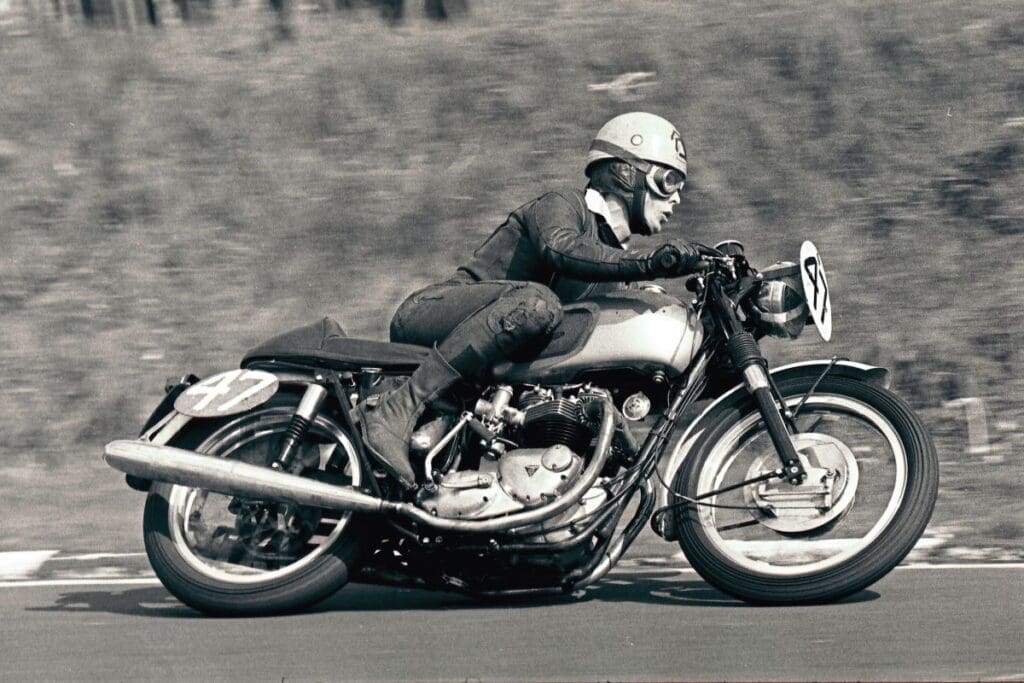

Arriving just before the Honda 750, the first Trident got rave reviews in the press. Cycle World called it a “stirring sight” and “unique”, raving about the near-120mph top speed. The three-cylinder layout was a massive hit, with Cycle World describing the Trident as the “most exciting motorcycle in the world today.” It loved the fact that the extra cylinder made it different, that the engine was more efficient, and the frame design meant it could handle more quickly than rivals.

The magazine was pleased that by adding just one extra cylinder, the Trident had a smaller frontal area than a four, and was cheaper to buy, too. The smoothness compared with a twin and the way the engine performed were other bonuses. It loved the way the engine hung together, the single plate clutch, and the smoothness of the power transmission.

It commented on a need to slip the clutch two-up and admitted that not everything was perfect, disliking the quality of the trim. The three pipe silencers were considered a bit tacky and Cycle World suggested that those used to the nimble nature of the Triumph twins might find it a bit cumbersome. But it was still dubbed a “connoisseur’s” motorcycle.

And then just a few weeks later, Honda brought out the CB750.

The first T150 Production models

The Engine

The Triple had a dry sump engine with a 120-degree crankshaft, made by forging it as a 180-degree crank, heating it again, and then twisting it. Balance was achieved by internal webs, and there were two sets of plain main crankshaft bearings in the middle section using very high quality Vandervell material normally used in racing car engines with a ball and roller bearing in the end castings.

There were three individual crankcase sections, with two camshafts running pushrods front and rear in the Triumph style.

The crankshaft was dropped into the centre crankcase and clamped in place with plain bearing caps, and the two other cases bolted on either side, while the section of crankcase, which was to hold the gearbox, extended backwards from the centre. There were two pushrod tubes on either side of the cylinder block, with two pushrods in the right-hand tubes and a single pushrod in the left.

The cylinder head was a single casting, with two separate rocker boxes. The gear box had four speeds originally, and a single plate Borg and Beck clutch, driven by a triple row chain. Initial tests showed the Trident was much smoother than the 650 twin, but not much wider or heavier, and would turn out 58bhp and was considerably faster.

Frame and running gear

The Triumph frame was derived from the Bonneville, with a single downtube, a duplex cradle, and a bolted-on rear subframe. Because of the single down tube, the middle exhaust split into two as it came out of the head, one to each of the outer downpipes.

The forks were similar to those used on the twins, as was the front brake, and the shock absorbers were shrouded. There was an oil tank on the right, hidden under the side panel, and a bank of three Amal Concentric Mk1 carbs, controlled from a single cable. Switchgear and electrical equipment was Lucas, with all that entails. The Trident in its square-cut spec wasn’t a terrible seller in the UK, but the Americans didn’t like it. In fact, they didn’t like it so much that by 1970 it had been relaunched as a traditional Triumph, with a 1960s tank, new side panels and more conventional silencers in what was known as the Beauty Kit. That big old brake was replaced by the conical hub, there were new forks, there was a proper front mudguard, and the silencers were replaced by a rather funky set of megaphones. In mid-1972, it got a disc brake at the front, reverted to the square edge tank, got a fifth gear, and the big cigar-shaped silencers from the T140.

Originally conceived as a BSA model, the X-75 Hurricane was launched in 1973 as a Triumph following the collapse of BSA in 1972. The Hurricane, with its stylish, sloping cylinders, extended front forks, high handlebars, triple-stacked silencers on the right-hand side, and beautiful tank and seat unit, was an instant classic, widely regarded as the first factory custom bike. Only about 1170 Hurricanes were built during its short production run and most were exported to the USA.

Death of BSA and the T160

By this point, production, however, was in a state. The Trident engines were made by BSA at Small Heath, but the frame and final assembly was done at Meriden. When the factory blockade began at Meriden in autumn 1973, the production of the BSA-Triumph flagship bike came to a halt. With no frames being made at Meriden, the new NVT company had to expensively retool at Small Heath, where BSA production had come to an end, and no Tridents could be made until 1974, by which time the kickstart-only Trident was looking rather old hat in comparison to rival machines.

In 1975, a new version of the Trident appeared – the T160. This used the format of the Rocket 3, with the barrels leaning slightly forwards, but matched to the five-speed gearbox and with Trident style timing and gearbox covers. There was a new left-foot gearshift to comply with US regulations, and there were changes to the primary drive chain and the rev counter drive. But the biggest difference – and the most important – was the addition of an electric start at last, operated via solenoid and driven by gear to the back of the clutch. It was Triumph’s first big production bike with an electric start. The exhaust system was split into two at the middle cylinder, making it a three-into-four-into-two, there were discs at the front and back, and the tank got a whole new look. It was one of the most beautiful motorcycles made by anyone in the 1970s.

Sadly, recessions, oil prices, and more modern competition meant that this wonderful final effort was short-lived. Production at Small Heath came to an end as 1975 closed, though you could still buy a T160 into 1978 thanks to NVT selling a batch of Triples as the Triumph Cardinal, left over from a cancelled order from the Saudi Arabian police.

There was an attempt to build a four-cylinder Quadrant, and an overhead cam version, and an effort by staff at Meriden to shoehorn a T160 engine into a heavily modified T140 Bonneville frame.

The Trident refuses to die

In 1976, Les Williams, late of the Triumph race shop, started the Triumph spares company LP Williams, dealing in spare parts and performance upgrades. He created replicas of the Trident-based Slippery Sam race machine and produced a Marshalls TT Replica, based on a T160 Trident and in the style of the Production TT Racing Tridents. After the closure of NVT, he followed the Slippery Sam Replicas in 1983 with the creation of an updated sports-touring version of the T160V, known as the Legend. Production of the Legend continued until 1992 and 60 were built. Although badged as Triumph models, the Legend machines were officially made as Williams.

Large-capacity Tridents

Jerry Robinson, from the TR3OC, has a special insight into the experimental big bore Tridents: “There were two different routes followed to larger capacity. First there was the large bore with the same stroke and the other was long stroke with the standard bore for 871cc, or a +40 thou over-bore to make it nominally 900cc. Neither of these iterations was to be called the Thunderbird 3. That name was to be used on the development of the T150 that became the T160 with the sloping cylinders from the R3, electric start and left-foot gear change. The airbox and silencers were designed to help meet tightening US emissions regulations, and the forward slope of the cylinders helped accommodate the additional space needed for the starter and airbox. One of the first designs for the T160, which was to be called the Thunderbird 3 until the name was dropped, included a single-sided silencer and high rear light cluster. They were dropped for the production model. There is an ‘archaeological remnant’ of the possible use of the Thunderbird name for the T160. All the rider manuals contain an image of the side panel with the Thunderbird logo on it! No production machine ever had that. The name may have been dropped after legal challenges by the creator of Thunderbirds, or by Ford, which claimed it owned the Thunderbird name. Neither story has been satisfactorily verified!

“The large-capacity machines were never thought of as the Thunderbird 3. The large bore motor was declared one of the best bikes Dave Croxford had ridden and was seen as a road machine, while the long strokes were seen as race motors. Three long stroke motors were built. Two were numbered T180 001 and 002. T180 002 was built into a complete machine by Les Williams and Steve Brown and tested by Bike magazine in 1979. T180 001 was configured for a hybrid chassis of Norton Isolastic front loop and R3 rear frame loop. This frame may still exist, but its whereabouts are now unknown. That motor (T180 001) is owned by the TR3OC. This was built into a complete machine styled like a T160 with the single-sided stacked silencer to represent how it might have looked, had it reached production. One long stroke motor, known only as the ‘race motor’ by the factory, was raced at the British GP meeting at Silverstone in August 1975. Dave Croxford rode it to sixth place against Grand Prix two-stroke machines. That motor still exists, too. A notable feature of the T180 long stroke motors was the use of line contact rockers, as used in racing practice on works machines.”

A brief ride – by Matt

I was lucky enough to take the T150V you see in the photos around for a good ride. Starting is easier than I imagined thanks to its owner, Hutch, advising of the correct procedure, and it ticks away nicely once warm. This one is fitted with Mikuni CV carbs, which don’t look out of place and seem to give the throttle a modern feel once warm, though the clutch does still feel more old-fashioned.

Away we go and to keep the revs down, I change up to second, then third, quickly fourth and – they all feel so close! Only after some time do I realise that this large machine thrives on revs, only coming really alive a good third or more through the rev range. Not that it doesn’t pull down below – it does, well – but there is a definite power increase at about 5000rpm.

When riding bikes for the first time, they come to you bit by bit. The brakes have that familiar feel of early disc systems like my BMW; they feel somewhat dead at first, unlike a modern bike that feels like the pads are chewing into the disc like a steak. But they do slow you down and they do stop you, with the reassuring rear drum there to balance things out.

Handling is nice, through slow corners and faster sweepers. It certainly doesn’t feel like the heavy bike I was expecting. And the handling feels – modern, predictable. The riding position is perfect (for me) as are the ‘bars, which dramatically help. Even potholes are not the torture they are on my plunger bike, nor even the modern Royal Enfield I’ve ridden there. I’m impressed.

You cannot ignore the sound… in fact, I wanted more noise! That triple firing order has a wonderful benefit of sounding great, which allied to me getting used to bringing the revs up before changing gear just gets better. It also means you’re going quite fast, compared to a 500cc or 650 Triumph. Several times did I look down to find at least 10-15mph more indicated than I expected on a 50-year-old bike. And, more importantly, the ease that the Trident took it under its belt.

I’d never experienced a Trident or Rocket 3, but I’m so glad I have now. What a treat! It’s a combination of old and new – old seating position, kickstart, controls, feel, sound – yet it thrives on revs, you can change gear without the clutch thanks to the good gearbox, the suspension works, and the speed is like a modern bike. Like a perfect ‘retro’ bike, because it is old!

Cliched, maybe, but the Trident is a real rider’s bike. And not just on the odd ride, but regularly, for long distances. B roads will be harder work, but nice A roads will have that triple singing away at you, rewarding a smooth riding style and getting you far further than you might on a 650 twin. Modern road speeds are no problem to a good Trident, the seat was comfortable, and with a little personalisation you could get your perfect riding position, extending your reach on it. There were many parallels between my beloved mile-munching boxer BMWs and the Trident, though I have to say the Triumph has a better soundtrack and similar amounts of personality. You know you’re enjoying yourself when you stop half way through a ride to look at prices of similar bikes online…

■ Thank-you to Jerry Robinson, Paul Barton and Norman Hyde for their help with this article.

OWNERS’ CLUB

Trident Rocket 3 owners club

BSA-Triumph triple owners are fortunate to have a dedicated owners club keeping the triple flame burning.

The TR3OC is dedicated to promoting the use of BSA and Triumph pushrod-engined three cylinder motorcycles. The Club is administered from the UK and has over 1250 members from around the world. TR3OC welcomes owners of standard and modified triples built using pushrod motors and publishes a bi-monthly magazine, Triple Echo. The club’s website is at www.tr3oc.com. Membership enquiries should be made through the club website or by email to [email protected] for Beezumph 30, the Club’s annual rally, are available at beezumph.com.

www.tr3oc.com

SPECIALISTS:

Norman Hyde

www.normanhyde.co.uk

LP Williams

www.triumph-spares.co.uk

Triples Rule (USA)

www.triplesrule.com

Specification: Triumph Trident T150V

ENGINE: 740cc air-cooled transverse dry sump ohv three-cylinder COMPRESSION RATIO: 9.0:1 CARBS: Three Amal MkI Concentric POWER: 58bhp @7250rpm TRANSMISSION: Four-speed right-foot shift gearbox, single plate diaphragm clutch FRAME: Single down tube double cradle with bolt-on rear sub-frame SUSPENSION: Telescopic forks with two-way hydraulic damping, swinging rear fork with three position Girling shock absorbers BRAKES: 10in front disc/7in rear drum wHEELS/TYRES: 3.25×19 (MkI) or 4.10x19in front and rear (MkII) ELECTRICS: Lucas 120w 12v alternator with Zener diode; three coils with contact breakers; 7in headlamp DIMENSIONS: Wheelbase 57in (1450mm), ground clearance 6.5in (77mm), seat height 31in (787mm) WEIGHT: 460lb (211kg)