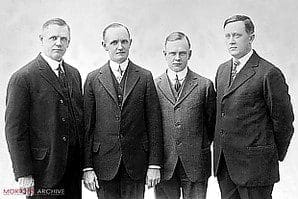

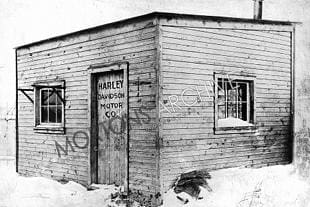

Friends since childhood, William S Harley the designer and Arthur Davidson the fabricator had been nurturing an idea to build an outboard motor, to reach their favourite fishing spots. But two wheels soon prevailed over two reels… In 1903, Arthur’s father erected a 15ft x 10ft backyard shed that bore the painted legend HARLEY DAVIDSON MOTOR CO and the foundations for a legend were in place.

1903-5: the first single

The first production Harley-Davidson motorcycle, its castings marked with serial number ‘1’, came into being during 1903. A minimal device, weighing less than 180lb, it was nevertheless substantially more than just a motorized bicycle. A one-gallon petrol tank hung below the single top frame rail, with a one-quart pannier oil tank above and a three-cell dry six volt battery (for the coil and points ignition) beneath, all bound together with two steel straps. The bike’s 24.74cu in (405cc) motor, with atmospheric inlet valve over a pushrod-actuated exhaust valve, was inclined forward to clear the low-slung fuel tank. The engine was clamp-mounted at four points, including a head steady, in what we now recognize as the conventional position within a purpose-built, single-loop, steel frame. Starting was by bicycle pedals, back-pedalling of which operated a brake within the rear wheel hub. A linkage of rods, chains and levers from the handlebars controlled the specially-developed 0.88in carburettor, and a sturdy leather belt fed direct drive to the 28in rear wheel. The belt was kept in tension by an outrigger wheel that could also slacken and thereby disengage the drive for short periods like a primitive clutch. Top speed would have been around 35mph, although the poor condition of most roads would have imposed a considerably lower limit.

A hectic decade later, the company would boast that one of its first bikes had recorded 100,000 miles without major mishap. A grey paint option for the uprated 1906 single led to the ‘Silent Gray Fellow’ nickname and advertising slogan. The Gray Fellows were actually a few decibels less silent on the open road, thanks to an ingenious mechanical bypass valve in the silencer. New, dual-spring leading link front suspension in 1907 paved the way for subsequent increases in power and weight.

A hectic decade later, the company would boast that one of its first bikes had recorded 100,000 miles without major mishap. A grey paint option for the uprated 1906 single led to the ‘Silent Gray Fellow’ nickname and advertising slogan. The Gray Fellows were actually a few decibels less silent on the open road, thanks to an ingenious mechanical bypass valve in the silencer. New, dual-spring leading link front suspension in 1907 paved the way for subsequent increases in power and weight.

1909: the first V-twin – Model 5D

With total sales more than doubling each year, Harley-Davidson felt secure enough by 1909 to introduce a 49.48cu in (811cc) V-twin as the easy route to extra power without loss of reliability. The Model 5D had a longer chassis to accommodate twin cylinders set at 45 degrees and a forward-mounted magneto. Unfortunately, its cylinder heads utilised the atmospheric inlet valves of the singles, which proved unsatisfactory in V-twin operation due to variations in crankcase pressure. Furthermore, the bike lacked a drive belt tensioner and was difficult to start. Only 27 Model 5Ds were built and the V-twin was not offered at all during 1910.

1911: getting it right – Model 7D

The Model 7D was the first example of V-twin evolution by the company, which by now employed 149 workers in a factory of some 10,000sq ft in Chestnut Street (later to become Juneau Avenue). Engine capacity was unaltered, but new cylinder heads with vertical cooling fins carried mechanical inlet valves that were actuated by exposed pushrods and rocker arms. Six and a half horsepower gave a top speed around 60mph, while a lower, reinforced, straight-downtube frame improved handling.

The new V-twin was a success. In 1912, a 60.32cu in (989cc) version offered direct drive to a rear wheel hub-mounted clutch, which allowed the option of chain drive for the Model X8E. This attention to the power train was largely inspired by the competition success of Harley-Davidson’s older-established rival Indian, most notably at the preceding year’s TT races in the Isle of Man, where chain-driven Indians had taken the top three places. 1913 saw the Model 9 single catch up with the mechanical development of the twins, and all the bikes began winning amateur racing events with some regularity. Although Walter Davidson had achieved national success as early as 1908 riding the company’s product, the first factory Model K racer did not appear until 1914, listed alongside 4 roadsters; the following year saw a full 8 racing models listed alongside an identical number of road bikes in the sales catalogue. Both on the road and on track, the popularity of the V-twins became overwhelming, pointing the way towards the company’s long-term future.

The Model 11J V-twin of 1915 (see page 18) introduced a 3-speed gearbox with foot-operated clutch that represented a giant leap forward in terms of modernity. The new model also offered, for the first time, the option of an electric headlight. WWI brought a steady export demand for the new J models, mostly with sidecars, but competition at home now loomed from cheap, production line-built Ford cars. Enclosed valve springs and a gear-driven oil pump helped Harley-Davidson to forge a reputation for reliability during wartime use, although even here it ceded to Indian as the dominant military supplier. Nevertheless, Bill Harley remained convinced that racing success was the way to fire the public’s imagination for motorcycles and so Harley-Davidson took on the mighty Indians where it counted most – on the track.

The Model 11J V-twin of 1915 (see page 18) introduced a 3-speed gearbox with foot-operated clutch that represented a giant leap forward in terms of modernity. The new model also offered, for the first time, the option of an electric headlight. WWI brought a steady export demand for the new J models, mostly with sidecars, but competition at home now loomed from cheap, production line-built Ford cars. Enclosed valve springs and a gear-driven oil pump helped Harley-Davidson to forge a reputation for reliability during wartime use, although even here it ceded to Indian as the dominant military supplier. Nevertheless, Bill Harley remained convinced that racing success was the way to fire the public’s imagination for motorcycles and so Harley-Davidson took on the mighty Indians where it counted most – on the track.

1916: racing power – eight valves

Indian had introduced an eight-valve V-twin racer in 1912, offering it for sale at little more than the cost of the roadster upon which it was based. Harley-Davidson’s approach was different. Constrained by national racing regulations to offer its production-based racer for sale to the public, it priced the machines at five times what the roadsters cost, thereby keeping the bikes and any associated racing glory out of private hands. The eight-valve ohv engines had capacities not exceeding 61cu in (1000cc), the earliest models running a single cam with four lobes between the barrels. Twin cams arrived in 1919, by which time the cylinder heads had adopted 90 degree valve angles and hemispherical heads following aviation engine practice. The motor was a stressed member of the frame, held in place by flat metal plates. Silencing was minimal to the point of sometimes having no exhaust at all! Everything about these racing machines was designed to maximise available horsepower for top speed. Handling didn’t really come into it, the short-wheelbase frames harking back to the very first bicycle affairs that could barely cope with 3hp; the racers put out more like 15.

The bikes, built in very small numbers, duly achieved their aim and Harley’s ‘Wrecking Crew’ race team rose to national prominence on banked oval board tracks and in endurance road races across the USA. Engines were sometimes sent abroad; Freddie Dixon subsequently set the first 100mph race average at Brooklands on a factory 8-valver. The four-lobe cam, an early racing development, found its way to the v-twin Model 17J roadster in 1917.

1919: lightweight sports – Model W

1919: lightweight sports – Model W

Inspired by the Douglas design, the fore-and-aft Model WJ Sport Twin was a bold stab at the post-war sporting and recreation role for the motorcycle (the Model WA, painted in identical olive green, was its military counterpart). Somewhat like a Moto Guzzi single in appearance with a truncated frame and large external flywheel, its 35.64cu in (584cc) flat twin motor was over-engineered for a meagre 6hp, although the whole bike was lightweight at just 265lb. Inlet and exhaust gases ducted through metal tubes on the right-hand side of the engine, heating the intake charge in a manner felt likely to aid combustion. Both the engine’s layout and its design were aimed at ease of servicing, while optional drive chain enclosure reduced maintenance intervals. The bike’s front fork was an unusual affair, resembling a girder unit but with trailing lower links that connected to a central spring by rods and upper links; the arrangement allowed the front wheel to move in a vertical plane independently of its mudguard. A rear luggage rack was standard.

Everything about the Model W seemed different and new, in line with its emerging market. Nonetheless, the American public showed little interest in the radically-configured and frankly, ungainly machine, despite reliability trials that showed its sporting potential. Traditionalists preferred the 36.4cu in (596cc) V-twin Indian Scout, although Harley’s flat twin was better received in Europe, where V-twins were less iconic. The cessation of US government wartime contracts hit sales targets hard. Works racing efforts were shelved in favour of a new emphasis on streamlined styling and reliability alongside increments in performance. The flat twin experiment was discontinued after just four years and the Model J in various forms became the factory’s flagship. However, the Model W’s undoubted export success did prompt some factory executives to examine overseas markets first-hand. They returned with evidence of a resurgence of interest in single-cylinder machines.

The Twenties: single minded

Two new types of engine met the demand for singles. The Model A (magneto) and B (battery) side-valvers were economy transport rated at 8hp. The Model AA and BA overhead-valve machines were more sporty at 12 horsepower. Both were competitively priced and sold well. The new 21.1cu in (346cc) singles were particularly noteworthy for featuring detachable cylinder heads, incorporating ‘squish’ technology developed by Harry Ricardo. The ohv Model S ‘Peashooter’ race bikes fared well in competition, particularly in the hands of Joe Petrali, but it was the side-valvers that pointed towards the future. Not only were Indian and Excelsior already committed to side-valve V-twins for the road, but highly tuned flatheads had been proven, in the hands of Indian’s tuning genius Charley Franklin, to be more than a match for eight-valve overheads on track – at least for the present.

The 1930s: Flatheads rule

The 1930s: Flatheads rule

The Model D of 1929 introduced side-valve technology to the V-twin range, just as the stock market crashed. Although its chassis and cycle parts appeared superficially similar to previous models, the Model D’s engine was new. The side-valve V-twin displaced 45.32cu in (743cc). A duplex chain delivered primary drive efficiently to a three-speed gearbox. Twin headlights, fitted only during 1929 and 1930, gave a distinctive front profile. Quieter and less expensive to build than ohv variants, it made barely adequate power of around 18hp, even when boosted by high-compression cylinder heads on the Model DL. Its big brother, the 73.73cu. in (1208cc) Model V flathead made more power, but was plagued by reliability problems. Understated in black cast-iron, the new ‘flathead’ motor looked squat and unprepossessing, yet (once reliability issues were fixed) it would repeatedly prove to be the company’s mainstay during dark years as export markets (and the demand for singles) collapsed overnight. Little income during the years of the Depression meant little development, so from 1933 the factory followed the car market’s lead in adopting Art Deco styling motifs with bright and contrasting colours in a bid to attract buyers.

1936: first of the moderns – 61 E

In many ways, the Model EL of 1936 was the first of the recognizably modern Harley-Davidsons: the great-great-grandfather of the current range. Unlike the first side-valve V-twin, it was a new motorcycle throughout. Visually striking, its 60.33cu in (989cc) ohv, dry sump engine was characterized by twin chromed pushrod covers rising to polished alloy rocker boxes (their shape suggesting the ‘knucklehead’ nickname) atop each cylinder head. A racing layout in the cylinder heads helped flow gases from the 1.25in Linkert carburettor to a fishtail silencer. It made 40 horsepower in high compression EL form, enough to propel its four-speed 565lb mass close to 100mph. The bike’s twin downtube frame handled well enough, too, at least once it had been reinforced from 1937 onwards. Front fork tubes became oval in section, wheel sizes dropped to 18” and the seat height dropped to just 26in. Instruments were mounted in a console on the petrol tank.

Racer Joe Petrali quickly established the new model in competition, setting a new flying mile speed record on Daytona beach of 136.18mph that eclipsed the current record holders, Indian, by 10mph. Indian had no equivalent to this new engine. The Milwaukee factory’s launch of the 81.65cu in (1,338cc) VLH side-valver in the same year stole further territory from its Springfield rival. Further flathead development led to, among other applications, a competitive Model WR factory racer and a dependable Servi-Car utility trike. WWII saw Harley-Davidson finally overtake Indian in vital military contracts. Post-war, the demand for big twin motorcycles was high, and Harley-Davidson rose to the challenge. Its side-valve engines had proved themselves during arduous wartime conditions, but development of the knuckleheads (fewer than 2000 of which had been supplied to the military) had continued behind the scenes, possibly even accelerated by rapid technological advances in other fields.

Racer Joe Petrali quickly established the new model in competition, setting a new flying mile speed record on Daytona beach of 136.18mph that eclipsed the current record holders, Indian, by 10mph. Indian had no equivalent to this new engine. The Milwaukee factory’s launch of the 81.65cu in (1,338cc) VLH side-valver in the same year stole further territory from its Springfield rival. Further flathead development led to, among other applications, a competitive Model WR factory racer and a dependable Servi-Car utility trike. WWII saw Harley-Davidson finally overtake Indian in vital military contracts. Post-war, the demand for big twin motorcycles was high, and Harley-Davidson rose to the challenge. Its side-valve engines had proved themselves during arduous wartime conditions, but development of the knuckleheads (fewer than 2000 of which had been supplied to the military) had continued behind the scenes, possibly even accelerated by rapid technological advances in other fields.