For years motorcyclists in the UK have been told that such-and-such a machine would be too expensive to produce, or too difficult. The old arguments that usually begin with “Who wants a high-revving multi, when the good old single will last for twice as long?” no longer hold water. It is almost as though Honda has torn up the rule book and said “To hell with it! Let’s have some exciting machines!

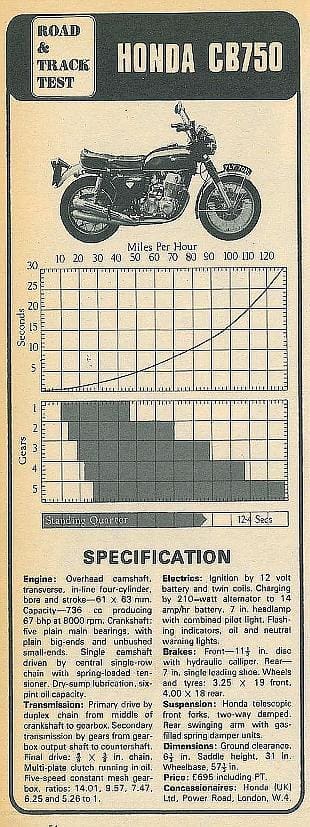

Take the specification of the CB750: 750 cc transverse in-line four-cylinder with single overhead camshaft and five-speed gearbox. It sounds more like a works racer to our “brain-washed” minds, but in fact this hunk of Honda is as docile in traffic as it is impressive on the open road.

Honda’s racing experience both in production cars and motorcycles has had a tremendous influence on the design of the CB750. Without such experience, the end product could have been an unwieldy horror—a power pack with a mind of its own!

Engine width is obviously a critical factor with a transverse four. This has been kept to a minimum by taking the power to the clutch by chain from the centre of the crankshaft. Chain drive, rather ‘than the use of gears, also simplifies crankshaft construction and saves weight.

Another factor which reduces engine width is the “under-square” set-up of the motor. The bore is 61 mm and the stroke 63 mm. But this unusual (for Honda) configuration has no detrimental effects and as the 750 peaks at a safe limit of 8500 rpm and is in a relatively low state of tune, it has punch combined with tractability.

With fuel consumption in mind, no doubt, valve overlap has been kept to a minimum. Fuel consumption was in fact quite reasonable at an average of 40 mpg. Petrol-conscious riders may squeeze a few more mpg, others a good deal less, but let’s face it, if you buy a CB750 you shouldn’t be exactly on the breadline!

With fierce acceleration and 67 bhp on tap one would expect the drive chains to take a real bashing. The rear one does in fact have to be constantly adjusted during the first 1000 miles or so of its life—you always know when it is slack because first gear goes in with a loud clonk.

With fierce acceleration and 67 bhp on tap one would expect the drive chains to take a real bashing. The rear one does in fact have to be constantly adjusted during the first 1000 miles or so of its life—you always know when it is slack because first gear goes in with a loud clonk.

The primary chain tension is taken care of by the inclusion of a spring-loaded rubber tensioner which bears against the chain’s twin runs.

Clutch action is very positive, but I found it a trifle noisy until the technique of changing gear was completely mastered. In a way, it was like riding a BMW with engine-speed clutch. The speed of crankshaft and clutch is not all that different, so this would probably account for the Bee-em feel.

As with other Hondas, the finish was first class. During the two months in which we had the machine, it snowed, rained, hailed and we even had some fog. But the only parts which showed any signs of corrosion were the exhaust flange nuts and the small bolts which hold the handlebars. The latter, as it happened, came up like new when cleaned and polished, but the rust on the exhaust nuts was more serious. The rear chain stayed oily, but as I’ve said, it did need constant adjustment.

The motor stayed oil-tight even after a merciless thrashing on the Snetterton track. A slight oil mist appeared on the front, but there were no leaks as such. And don’t forget that this machine was not cleaned for two months!

Starting was always easy. I used the kickstarter only once and that was to test its action. It worked well and was sensibly geared to spin the motor quite sufficiently for a second kick start from cold.

The electric starter, however, made you forget such mundane things as kickstarts and the merest touch of the button with choke lever right up would make the big four burst into life. Warming it up was a problem on very cold mornings and needed a lot of choke juggling before the bike would pull away. Once warm, choke could be ignored after a few hundred yards and it was not long before the power would come in smoothly.

Throttle response was instant in the lower gears, but I found it very controllable and only experienced wheel spin if I wanted it. The weight of the machine discouraged the back wheel from “stepping out” even on wet, greasy roads and the handling was surprisingly good at all speeds.

Top gear was very much like an overdrive for normal use, especially with the 70 mph limit. For rapid overtaking, it was always best to drop into fourth when cruising in the 60s, but when really tramping at ton plus speeds in fourth gear, the motor seemed to sigh with relief as it was snicked into fifth and 120 mph came up on the clock at just under 8500 rpm.

One of the most important points about a performance machine is the braking. Will it stop? Are the brakes the on-off variety with nothing in between? Happily, the Honda is particularly well endowed in the anchor department.

The front brake is an 11.5in. hydraulically operated single-calliper disc. This proved almost completely fade-free from ton-plus stops and could be used with complete confidence under all conditions.

Such was the feel of the disc, that there was no heart-in-mouth sensation even when traversing London’s wet and greasy roads.

The rear brake was also effective, but too fierce for my liking. In the wet I treated it with a great deal of respect. However, with both brakes hard on, a braking figure of just under 33 ft. was obtained on a dry concrete surface—can’t be bad for a bike weighing nearly 500 lb. can it?

Ground clearance was more than adequate. It takes a hairy rider to scrape the four although the roadholding was such that it could be done.

There were never any complaints from pillion passengers either. The seat is well padded and allows plenty of room for all but the grossest couple. Nor was there any unpleasant vibration transmitted through the footrests. In short, for rider and passenger the CB750 was a first-class high-speed touring bike. Riding position was pleasant, if a little high for “tanking” it. Controls were thoughtfully placed and instruments easy to read.

One addition I would like to see on the bike is a rear mudguard flap. When riding over a wet surface the pillion rider’s back was in a constant shower—a simple addition, but in my opinion a worthwhile one.

In an age which is becoming increasingly noise conscious, this machine should cause no offence. Thrashed about town, you could raise a few eyebrows, but the CB750 is far quieter than many of its lower-capacity brothers.

The electrics on the 750 are all 12 volt. To cope with the huge demand from flashers, electric starter, warning lights, etc., there is a 12v/14 amp/hr battery which is fed by a powerful 210-watt generator.

Night riding up to the legal limit was quite safe and the dipper gave a reasonable cut off when meeting oncoming traffic.

The light controls were operated by a thumb switch next to the twist grip. This enabled you to select off, pilot light, dipped beam and main beam without taking your hand from the throttle. A parking position was obtainable by turning the ignition switch and then removing the key, which meant that you could leave the lights on and nobody could turn them off.

So there you have it. If you want searing acceleration which will take you from 0-100 mph in 12 seconds, powerful braking and a well-finished machine which can stand up to all the thrashing, the CB750 could be the bike for you.