FOREWORD: From across the Atlantic, last October, came the dismal news that the demolition men had flattened the old Indian factory in Springfield, Massachusetts — though in fact it was just a shell; having been gutted by fire some years before. Peak year of Indian production had been 1913, when the company claimed that theirs was the world’s largest motor cycle factory; as, indeed, it probably was. There is, therefore, a particular poignancy in this account of one of the most illustrious models to be produced at Springfield, the rear-sprung 996cc Powerplus side-valve of 1918.

During the first thirty years of motor cycle production, America could well be said to have led the world in design, durability, sales and speed. Often called the Golden Days of American Sport, the era ended in the mid-1920s when our economic growth and affluence expanded so much that the citizenry could afford the luxury of a mass-produced automobile.

Indian was the undisputed leader in those early days, with an annual line-up of exciting models that bristled with innovative ideas. The marque had been born in 1901, when Carl Oscar Hedstrom, a Swedish immigrant, teamed up with bicycle manufacturer George Hendee in Springfield, Mass. Indian was to grow until it was the best-known motor cycle in the world, with exports to Australia, New Zealand, Japan, England, and many European countries.

Co-founder of Indian, Hedstrom was a brilliant designer, and it was his inlet-over-exhaust vee-twin which first took the make to prominence; he resigned in 1912, but in 1914 Charles B. Franklin, from Ireland, was recruited to the engineering department. Franklin carried on the tradition of superb engineering that kept Indian in the news until motor cycle sport and usage declined here in the middle 1920s.

Co-founder of Indian, Hedstrom was a brilliant designer, and it was his inlet-over-exhaust vee-twin which first took the make to prominence; he resigned in 1912, but in 1914 Charles B. Franklin, from Ireland, was recruited to the engineering department. Franklin carried on the tradition of superb engineering that kept Indian in the news until motor cycle sport and usage declined here in the middle 1920s.

Charles Franklin, of course, was also a racer of considerable ability, and together with winner Oliver Godfrey and third man Alan Moorhouse he had helped to give Indian a stunning 1-2-3 in the 1911 Senior TT, being held for the first time over the Isle of Man’s mountain course. The Americans used two-speed gearboxes and chain drives that did not slip, and their victory over the hub-geared belt-drivers helped Indian to establish a world-wide market — something nobody else had achieved at that time. By 1913, for instance, Indian had established more than 2,000 dealers all over the world, and that year they would sell 32,000 of the bright red products of Springfield.

Hedstrom’s last stroke of genius before leaving was the leaf-sprung swinging-arm frame introduced into the 1913 range though in truth this was motivated by the success of Flying Merkel’s 1909 spring frame model. But by 1915, the Indian management felt that the Hedstrom inlet-over-exhaust engine was reaching the limit of economic development, and Charles Gustafson (formerly with Reading-Standard) began under Franklin’s guidance to experiment with a new side-valve design — a concept that took many years to soak into the thick skulls of British designers!

The Powerplus featured a reliable magneto, an internal-expanding rear brake (but no front brake!), a primary kick starter to replace the earlier bicycle pedals, a three-speed countershaft gearbox, and the Hedstrom-designed swinging-arm rear suspension. By contrast, the typical British bike of 1916 still used hand-pump lubrication, vee-belt rim brake, a rigid frame, and exposed valve gear with all the leaking oil. Single-speeders were still common then in England, which all proved just how advanced the Powerplus really was.

Genuine classic

With such a design, the Powerplus can rightfully be called a genuine classic — one of the few American models to be accorded this honour. But by the middle 1920s the rising standard of living in the USA took people off their bikes and put them into the luxury of an automobile. The Europeans, and the British in particular, assumed the leadership, since a booming market fostered an intensive effort to build better motor cycles.

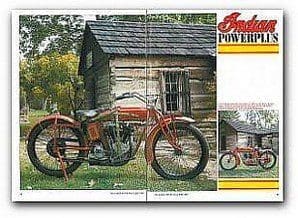

Being of a simple and rugged design, many of the early American motor cycles have survived. Restored to perfection they have become prestigious in anyone’s collection of vintage bikes — and one of the finest examples of early American superiority is the Indian Powerplus pictured here, which has been exhibited many times in Idaho, on the slopes of the Rocky Mountains. It was restored by the late Fred Edgin, of Boise; a man who in semi-retirement earned his keep restoring antique automobiles for customers who appreciated the work of a craftsman.

Being of a simple and rugged design, many of the early American motor cycles have survived. Restored to perfection they have become prestigious in anyone’s collection of vintage bikes — and one of the finest examples of early American superiority is the Indian Powerplus pictured here, which has been exhibited many times in Idaho, on the slopes of the Rocky Mountains. It was restored by the late Fred Edgin, of Boise; a man who in semi-retirement earned his keep restoring antique automobiles for customers who appreciated the work of a craftsman.

Fred, who passed away in 1983, rode this machine in his youth, bought it back half a century later, then restored it to a show-winning condition.

Several years ago I had the opportunity to visit Fred, photograph his bright-red Power-plus and ponder the bike’s visionary specification. Spending the day with the old twin had a profound impact on me, mostly because I had always been so wedded to British motor cycles (I have five Velocettes in my collection) and the Indian appeared so far ahead of its time. It really got to me.

After photographing Fred’s pride and joy we sat down and looked over the almost new-looking brochure for the bike, which he still treasured. According to the history books, the spring-frame idea created quite a furore when it was introduced in 1913. For 1915, Indian changed from a two-speed to a three-speed gearbox, then for 1916 the 996cc Powerplus engine replaced the older inlet-over-exhaust design.

Indian-Schebler

The narrow vee-twin had a longish bore-to-stroke ratio of 3 1/8in x 3 31/32in, providing an actual capacity of 60.88 cubic inches. The con-rods and crankshafts ran on roller bearings, while the three-ring cast iron pistons ran in east-iron cylinders and heads. Carburation was by a single Indian-Schebler unit, and originally a Dixie magneto fired huge Splitdorf spark plugs. The worm-gear-driven, plunger type oil pump was housed in the crankcase.

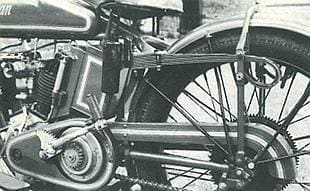

Primary drive was by chain to a stout multi-plate clutch which operated dry, and the left-mounted kickstarter quadrant engaged with an external pinion outboard of the clutch. The three-speed gearbox had tall ratios of 4.0, 6.0 and 10.0 to 1— an indication of the substantial torque produced by the big mill.

Perhaps the most remarkable point about the Indian Powerplus was its spring frame. The actual swinging-arm rear fork was similar to today’s standard practice, but the rest of the design was not at all like 1985 layout. The springing medium was a pair of laminated leaf springs, carried horizontally and firmly bolted at their front ends to the main frame below the saddle. The rearward ends of the springs were connected to a pair of vertical rods, the lower yokes of which pivoted at the fork ends.

Perhaps the most remarkable point about the Indian Powerplus was its spring frame. The actual swinging-arm rear fork was similar to today’s standard practice, but the rest of the design was not at all like 1985 layout. The springing medium was a pair of laminated leaf springs, carried horizontally and firmly bolted at their front ends to the main frame below the saddle. The rearward ends of the springs were connected to a pair of vertical rods, the lower yokes of which pivoted at the fork ends.

There was no provision for rebound damping, but the two (or maybe three) inches of wheel travel was two (or maybe three) inches more than a rigid-frame model provided! About the only problem experienced with the Indian design was a slight wobbling at high speeds over rough roads, caused by twisting of the rather spindly swinging-arm, and thus tilting the rear wheel.

The front fork was not quite so visionary. Again a laminated leaf spring was employed, in conjunction with trailing links, and vertical travel was very limited. This type of front suspension was a common American practice then, and it would be many years before any real progress was to be made (indeed, it was still fitted to the military Model 340B supplied to the Allied Armies in World War Two!).

Running gear of the Powerplus comprised 3 x 28in beaded-edge tyres on steel rims. There was no front brake, but the rear wheel had an unusual arrangement whereby a pedal on the right worked a conventional internal-expanding brake, while an external-contracting band brake on the outside of the same drum was actuated by pushing the hand-operated clutch lever to its forward position. Compared to the British caliper brake, this was a great deal of stopping power. (Yes, but you are still only stopping one wheel — and an external band brake is useless in the wet anyway. Editor).

All mounted on the right-hand side of the fuel tank, the controls consisted of the gearshift lever operating in a gate, a push-down compression-release rod, and a vast clutch lever pivoting at the base of the crankcase and guided by a quadrant bolted to the tank side. The right-hand twistgrip worked the spark advance-and-retard, and the left twistgrip was the throttle. It may all seem very clumsy today, but for 1918 it was considered to be a pretty good set-up. There was also a nice speedometer complete with odometer (mileage recorder), and a big plated Klaxon horn on the handlebar to give out its distinctive “arr-ooo-gah!” warning note.

The fuel tank, a two-piece affair secured by a central cover strip, held 3.75 US gallons, while the oil tank was of three-quart capacity. On the left side of the oil tank was an auxiliary hand pump, used for extra lubrication when running the motor really hard.

Spring frame

Wheelbase was a long 59 inches, which combined with the spring frame and sprung solo saddle to give the softest ride going in those days. We might also mention that the 1918 catalogue listed two versions of the Power-plus — one with generator, battery, and lights, and the other without. Lights weren’t required then, unless one rode after dark, and that isn’t so surprising for poor roads discouraged night-time travel.

Power output of the side-valve engine was listed as 15 to 18 horse power (though with no engine rpm quoted). Engines of that era were normally turning over at around 3,000rpm, so on the 4.0 to 1 top gear a performance of 60 to 75mph could be expected—which would have been really flying in those days, especially when you bear in mind the poor road surfaces in use.

According to the Indian brochure, the reason for switching to a side-valve engine was to obtain more power, reliability, and a clean-running engine — what they didn’t say was that it was easier, and therefore cheaper to build than its ioe predecessor. Concerning the long stroke, the brochure commented: “This long stroke gives the Powerplus its phenomenal power and a wonderful impetus to the pull, reducing gear shifting to a minimum and carrying on high gear excessive loads that a motor of short stroke could not negotiate without constant gear changing.” What a contrast to the contemporary Japanese approach of short strokes, lots of revs, and a multiplicity of gears to keep on the power curve!

According to the Indian brochure, the reason for switching to a side-valve engine was to obtain more power, reliability, and a clean-running engine — what they didn’t say was that it was easier, and therefore cheaper to build than its ioe predecessor. Concerning the long stroke, the brochure commented: “This long stroke gives the Powerplus its phenomenal power and a wonderful impetus to the pull, reducing gear shifting to a minimum and carrying on high gear excessive loads that a motor of short stroke could not negotiate without constant gear changing.” What a contrast to the contemporary Japanese approach of short strokes, lots of revs, and a multiplicity of gears to keep on the power curve!

An interesting performance option, and one that would have been highly illegal in England, was a pedal which opened three cut-out holes in the exhaust system. When extra power was needed on a long hill or for a bit of back-road racing, the rider could bypass the muffler and so obtain a few extra horses. All rather quaint, if somewhat antisocial.

The colour scheme of the Powerplus was striking indeed, being painted entirely in fire engine red, with gold striping on the tank, oil tank and mudguards. With nickel plating of many small parts, and black cylinders and heads, the old Indian was far more eye-catching than any contemporary British machine.

Other than its frailty, the Powerplus rear springing was basically as employed today; indeed, substitute a pair of oil-damped spring units for the upright rods, and replace the leaf springs by frame tubes, and you have the present-day system. But oil shocks were just not available in 1918, nor would proprietary units be in production until the 1950s. Even Velocette, who pioneered the system in prewar racing, had to make their own air-oil units.

But for all its far-sightedness the Indian springer was doomed. In 1920 the Franklin-designed Scout made its debut, with smaller wheels and a much lower seating position, and that model then became the basis for future Indian development. The spring frame got lost in the shuffle, so that no springers at all were built between 1924 and 1940 when the big 74-inch Chief and the luxurious Four appeared with plunger rear suspension.

After WW2, Indian staggered on, lacking the brilliance of their early days. The last true Indians were produced in 1953, after which the company imported British bikes. Even that failed due to bad management, so that the once proud company became just a memory.

Whenever, today, I stand before a bright-red Indian Powerplus a sense of history settles over the scene, and memories of the Isle of Man, Brooklands, American board tracks, and the early American road races permeate the air. Here, my friends, is a truly great motor cycle. View original article