Brutish but durable, the massive vee-twin has always held a fascination for American motor cyclists, brought up in the traditional “New World” philosophy that big and tough is better than small and refined. There were, of course, valid reasons why American motor cycles should have evolved along different lines than European models.

For one thing, narrow and winding roads, especially in England, fostered the development of smaller machines with nimble handling; Americans needed something that would cover vast distances effortlessly. For another, higher taxation rates in Britain and some European countries effectively discouraged the production of big-bore engines. Yet another reason was the European fascination with small objects of perfection, a mentality that bred smaller but well-designed motor cycles.

American industry

In its formative years the American industry had none of these limitations. In a young and empty country the logical answer was “lots of cubes” for the ultimate in power, durability and speed. The rugged vee-twin thus met with instant success so that by 1915 it was the standard USA design.

During the ‘twenties and ‘thirties a few single-cylinder models were produced here (plus a few other oddball designs such as flat-twins) but all failed in the market place, where the customer demanded max power and max speed. Engine size climbed to 61 cubic inches (1,000cc), to 74 (1,200cc) and even to 80 monstrous inches (1,300cc) as the manufacturers sought the ultimate in performance and longevity.

A few firms followed the path of the in-line four-cylinder, but all ultimately failed for various reasons poor design, high production cost, financial disaster — leaving the huge vee-twin as the sole survivor of American technology.

By the early 1930s, Harley-Davidson and Indian were the sole representatives of what had once been a proud industry with over 100 manufacturers. With the exception of the Indian Four (which endured until 1941) the entire Yankee output was of vee-twins, nearly all of side-valve design. These vast machines had gobs of torque low down in the rev range, a durability the equal of anything today, and a three-speed hand shift and foot clutch set-up that was slow and awkward.

By the early 1930s, Harley-Davidson and Indian were the sole representatives of what had once been a proud industry with over 100 manufacturers. With the exception of the Indian Four (which endured until 1941) the entire Yankee output was of vee-twins, nearly all of side-valve design. These vast machines had gobs of torque low down in the rev range, a durability the equal of anything today, and a three-speed hand shift and foot clutch set-up that was slow and awkward.

Huge and clumsy, the side-valve vee-twin plodded into World War II as the accepted American motor cycle, though an obsolete oddity to the rest of the world. But WW II was to change a number of things, one of them the American attitude to motor cycles. The war shrank the world quickly, and for the first time we Yanks began to think about places other than our own backyard. It took a while for the American mentality to lose its isolationism, but it did eventually happen, and we went on to become the world’s greatest consumer of foreign wheels.

The first crack in the wall came in the war itself, when thousands of US soldiers were stationed in England. Surrounded by British 350 and 500cc singles and twins, the GIs looked, touched, and rode them. They were easy to ride, with their peppy overhead-valve engines, light build, and slick hand clutch and foot gearshift. They were also fun — and that was what the GI remembered when he returned home after the war.

He wanted one of those neat bikes, and so opened a whole new chapter in American motor cycle sport. Few British bikes had been sold in the USA pre-war but now they began to arrive by the boatload. They looked exotic on the showroom floor, and were eagerly snapped up by riders who were in the process of casting off the “saddle tramp” image for a new and more sporting approach to motor cycling.

One of those watching the new trend was Ralph B. Rogers, president of the Indian Moto cycle Company in Springfield, Mass. A brilliant millionaire industrialist, Rogers had taken over the Indian company in November, 1945, at which time the factory was trying to recover from military to civilian production.

To Rogers the old factory seemed obsolete, and he wanted to bring modern merchandising techniques to (the stagnant domestic motor cycle industry. More particularly, he was alarmed by the rising tide of European motor cycles flooding into the USA. In 1946 we imported 9,064 machines, of which 8,596 were British; on the other hand, Indian sold only 2,800 of the massive 74-inch Chiefs that year, and therein lies our tale. Indian had either to meet the foreign challenge, or go under. Rogers chose to fight.

That fight began in 1945, after Rogers had purchased a small outfit named the Torque Engineering Company, founded by immigrant Dutchmen. Torque had an innovative designer called Briggs Weaver, who had designed a pair of lightweights (by USA standards, at least) on British lines. One was an 11 cubic inch (200cc) single, the Model 149; the other was a 22-inch (400cc) vertical twin, the Model 249. Both featured an overhead-valve engine, hand clutch, foot gear-change, and light weight — the qualities that the British were exploiting so successfully.

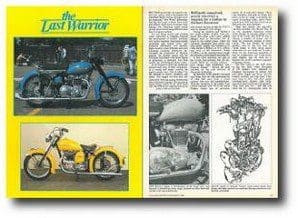

Indian had the production lines set up by the fall of 1946, and announced the new models, which had been enlarged slightly to become the 216cc Arrow single and 432cc Scout twin. They joined the venerable old 74-inch Chief on the sales floor.

Indian had the production lines set up by the fall of 1946, and announced the new models, which had been enlarged slightly to become the 216cc Arrow single and 432cc Scout twin. They joined the venerable old 74-inch Chief on the sales floor.

By 1947 the assembly lines were humming as the new breed of American motor cycle rolled out of the factory and into the hands of dealers all over the country. The new Indians proved to be stable machines, easy to ride, easy to start. They ran smoothly, and performed in an acceptable manner. Beautifully finished, too, and the only initial complaint concerned the small size, which didn’t seem right to riders raised on massive 45 to 80-inch twins.

The honeymoon didn’t last long, and in just a short while the new Indians were revealed to be a disaster. When they were ridden hard the main bearings broke up and rocker arms came apart. Magneto failures were common, and the gearbox often broke into many pieces.

By now dealers were angry and they flooded the factory with broken engines to be fixed under warranty. Brought up on the durable 45-inch Scout and 74-inch Chief, they just couldn’t understand how Indian could produce such flimsy and unreliable machinery.

Visibly shaken by the failure of the Torque design and all the attendant publicity, Rogers immediately called together his engineering staff. Still believing that the days of the big veetwin were numbered, and that the ‘nimble-handling Torque models were the only way to go, he ordered them to embark on a redesigning of the faulty parts.

Underlining the urgency were the results from the 1948 Laconia 100-Mile National Championship Race, in which no fewer than 50 of the new Indian vertical twins were entered, 12 of these having factory-prepared motors. Not a single one finished the race. It just had to be the saddest day in the history of the Indian company.

Rear springing

Discouraged but not yet defeated, Rogers continued to work on his lightweights. For 1949 plunger rear springing was added to the single (the twin having had it since 1947). However, the single was dropped in 1950, and the 432cc Scout was punched out to 500cc and renamed the Warrior in an effort to compete on more equal terms with the British BSAs and Triumphs.

A TT version of the Warrior was produced for desert racing, scrambles and track racing, and there were an enduro model with lights and a stripped out-and-out track racer. Max Bubeck went so far as to win the 1950 Californian Cactus Derby — but that fine win was one of the very few that Indian could ever crow about.

Part of Indian’s problem had nothing to do with the poor design of the bikes, but rather concerned the attitude of those riders who had traditionally ridden big vee-twins. Newcomers to the sport took to the European models readily enough, but there existed a tremendous amount of prejudice against “foreign” designs in the minds of die-hard Harley and Indian riders.

Just as Limeys caustically referred to American machines as crude threshing machines, so the bigots viewed the lightweight British bikes as so much tinny junk. These emotions bordered on sheer hate, with the fires being fanned even more by the two types of rider — saddle tramps on the American machines, versus the sports use by fans of British bikes.

Indeed, the post-war British invasion was the first real attack on American society’s attitude that only “white trash” rode motor cycles. That cultural revolution was not completed until the Japanese put everybody in America on two wheels. Such contempt for the smaller motor cycles by the veteran Indian riders was a real thorn in the side of Ralph Rogers, who had wanted to reach a whole new market with his “gentleman’s” motor cycle. He started as a man condemned in advance by the hard-line Indian enthusiast, and the condemnation was all the greater when the Arrow, Scout, and Warrior proved to be so fragile.

Indeed, the post-war British invasion was the first real attack on American society’s attitude that only “white trash” rode motor cycles. That cultural revolution was not completed until the Japanese put everybody in America on two wheels. Such contempt for the smaller motor cycles by the veteran Indian riders was a real thorn in the side of Ralph Rogers, who had wanted to reach a whole new market with his “gentleman’s” motor cycle. He started as a man condemned in advance by the hard-line Indian enthusiast, and the condemnation was all the greater when the Arrow, Scout, and Warrior proved to be so fragile.

This was a real tragedy for everyone, for the basic concept and design of this new breed of American motor cycle was really quite good. Weighing only 220 and 285 lb respectively, the original models appealed to many who were frightened by the huge vee-twins and by the unsavoury-looking characters who rode them. It was this big untapped market that Rogers was after, a market first breached by European imports then fully exploited by the Japanese some 20 years later.

The original Arrow was a pretty little bike with a telescopic fork and single saddle. Bore and stroke were 2 3/8 x 3ins, and it ran on a 7 to 1 compression ratio. A plain big-end bearing was used, camshafts were located high in the timing case to keep the pushrods short and light, and the cylinder and head were cast in light-alloy for light weight and improved cooling. The combustion chamber was hemispherical, and allowed the engine to develop around 10 bhp at 5,500 rpm. A Linkert carburettor and Edison magneto were specified.

The foot-shift gearbox (a novelty for America) had ratios of 6.12, 7.4, 11.69 and 17 to 1. Tyre size was 3.25 x 18in. while inch-wide, 6½ in-diameter brakes provided reasonable stopping power. Fuel tank capacity was 4 US gallons, with two quarts of oil held in a separate tank. Wheelbase was a short 52in, and that, combined with a weight of 220 lb, provided nimble handling. Performance was impressive for a 216cc, at 60 to 65 mph top speed.

The 26-inch Scout twin was just a double-up of the single, though with the addition of a spring frame. Weight was 285 lb — only half the weight of the vee-twin Chief, and probably 65 to 90 lb lighter than a British rear-sprung 500cc model.

Available in red, black, green, yellow or blue paint schemes, the Arrow and Scout were undoubtedly attractive. Light-alloy covers and castings were beautifully finished, and even today many observers will comment on how pretty the little’ Indians were.

When the 500cc Warrior vertical twin arrived for 1950, it was just a matter of opening the bore to 2.54 in to get the extra capacity. Compression ratio remained at 7 to 1, but now there was an Amal 15/16-inch carburettor.

When the 500cc Warrior vertical twin arrived for 1950, it was just a matter of opening the bore to 2.54 in to get the extra capacity. Compression ratio remained at 7 to 1, but now there was an Amal 15/16-inch carburettor.

Power output was 29 bhp at 6,000 rpm, and it would reach 90 mph on a 5 to 1 top gear ratio. Beefed up for increased reliability, the Warrior weighed 315 lb, which was still some 40 to 50 lb below that of the typical British 500cc springer.

The TT version was even faster and, with 7.5 to 1 compression ratio and hotter cams, it would top 100 mph if suitably geared. Fitted with a larger, 3.50 x 18in rear tyre, the TT Warrior was, perhaps, the first of what later became known as street scramblers. A wide variety of sprockets and parts were also available, for the dirt racing man.

Yet despite its apparent suitability for competitive use the Warrior failed to achieve very much. It was more reliable than the first Indian vertical twins, but still delicate when compared to the 750cc vee-twin Sport Scout side-valves that won the 1937, 1947 and 1948 Daytona Beach 200-Mile Races. A few riders and tuners did get their Warriors to perform quite well, but lack of reliability continued to plague the model.

Basic design

In retrospect, it is easy to see why it failed. Concept and basic design were excellent, but the whole motor cycle was just too light. Edward Turner, whose Triumph Speed Twin set the world off on the vertical twin trail, was shown a set of drawings of the 26-inch Scout in its early design stage. His comments were to the effect that the design looked good, but it was much too light to hold together. The genius of the British industry disliked, especially, the tiny main bearings — a viewpoint which was subsequently vindicated.

Designer of the original Torque models, Briggs Weaver had little experience of motor cycle engines. A marine engineer at heart he was accustomed to slow-revving marine engines where high stress factors were not involved. With such a background it is not surprising that Weaver’s designs were not up to the task of high revs and high operating temperatures; a fatal flaw in an otherwise brilliant concept.

Indian continued to build the Warrior until late in 1952, at which time production was halted on everything except the big 80-inch (1,300cc) Chief. Early in 1953 the Chief, too, was killed off and the Indian production line came to a permanent halt. For a few more years Indian imported and marketed British bikes until even that failed and Indian became just one more name in the history books.

Ralph B. Rogers was a man of great vision, a fact proved many years later when the Japanese came to dominate world markets with many excellent lightweights and truly modern merchandising techniques. Where his post-war Indians failed was in execution. Had the Torque designs been more robust, and their magnetos more reliable, it is conceivable that Indian would still be in business today.

At vintage motor cycle rallies where Indian vertical twins take their place in the parade, viewers are frequently surprised that America once made a serious effort to produce a ‘foreign’ motor cycle. Pretty and petite, the Indian verticals were the closest America ever came to abandoning the rumbling vee-twin that had been the very soul of the native industry for over 75 years. View original article