History records that the 1965 Isle of Man International Six Days Trial was one of the wettest in the event’s long and chequered history. The reason – as local folklore would have you believe – was that there were too many foreigners in the Island and as a result the Manx fairies brought the rain and mist down to hide it from their curious stares. In reality, the island was battered by the tail-end of Hurricane Betsy, although personally I much prefer the more romantic version.

What it meant for the international triallists were some grim riding conditions which brought numerous retirements. In their post-trial report The Motor Cycle led with the headline: ‘Manx tragedy: British teams a dismal failure’ and went on to lament that out of the 77 Brits who started, only nine managed to finish, and how all of the factory BSAs had retired through electrical problems. No such trouble had befallen the machines from Meriden which, despite their handling deficiencies, had all finished. In fact they had done rather well and of the three British Gold medallists – Roy Peplow, Ray Sayer and John Lewis – Peplow and Sayer were both Triumph-mounted.

You might question what all of this has to do with the bike – now owned by arch enthusiast Brian Casely – which I recently tracked down in darkest Dorset. The insignia on the petrol tank announces it as being a BSA although the power plant is instantly recognisable as Triumph; however, GOB 657D is no ordinary ‘TriBSA’ bitsa, but a rare piece of ISDT history. It’s one of a handful – believed to be three – of factory machines made for the 1966 International Six Days Trial in Sweden where, in the hands of Arthur Lampkin, not only did it survive 1200 miles over six long, arduous days but in doing so earned the BSA man a coveted Gold medal and helped the British team finish runner-up to the all-conquering East Germans in the International Trophy.

You might question what all of this has to do with the bike – now owned by arch enthusiast Brian Casely – which I recently tracked down in darkest Dorset. The insignia on the petrol tank announces it as being a BSA although the power plant is instantly recognisable as Triumph; however, GOB 657D is no ordinary ‘TriBSA’ bitsa, but a rare piece of ISDT history. It’s one of a handful – believed to be three – of factory machines made for the 1966 International Six Days Trial in Sweden where, in the hands of Arthur Lampkin, not only did it survive 1200 miles over six long, arduous days but in doing so earned the BSA man a coveted Gold medal and helped the British team finish runner-up to the all-conquering East Germans in the International Trophy.

The story of how the factory TriBSAs came about is an interesting and – at the time – a controversial one, so before we fire up the ex-Lampkin bike, we’ll return to the aftermath of the 1965 debacle.

The ACU called several high-level ‘crisis’ meetings where it was pointed out that ‘BSA had badly let the side down’ and their whole ISDT future was in jeopardy. Indeed, if ‘insider’ reports are to be believed BSA were told in no uncertain terms that such was the poor showing, BSAs would be replaced in the 1966 Trophy teams by two-stroke Greeves. As can probably be imagined this didn’t go down too well within the walls of Small Heath and the petulant response was: “If there are to be no BSAs, then there will no Triumphs either” – remember that BSA also owned Triumph by then – a reply which made the ever-diplomatic (some say back-pedalling) ACU seek a compromise.

As Jeff Smith had already proven in motocross, the Victor was a world beater but despite its superlative handling the single-cylinder engine lacked the stamina required for long-distance events like the ISDT. For the Triumph riders the completely opposite scenario existed; the engine was extremely reliable and durable, but the chassis was outdated and inferior to that of the BSA. To the impartial ACU the answer seemed to be an obvious one; simply combine the best parts of the two machines into one.

As Jeff Smith had already proven in motocross, the Victor was a world beater but despite its superlative handling the single-cylinder engine lacked the stamina required for long-distance events like the ISDT. For the Triumph riders the completely opposite scenario existed; the engine was extremely reliable and durable, but the chassis was outdated and inferior to that of the BSA. To the impartial ACU the answer seemed to be an obvious one; simply combine the best parts of the two machines into one.

This amalgam of BSA frame and Triumph engine – TriBSA – had long been accepted by scramblers as the perfect compromise but one severely frowned upon by Meriden’s top brass, especially if and when tried by a works rider. A point in question was the aftermath of the 1965 British GP at Hawkstone Park; a race in which John Giles brought the factory twin home in a strong fifth place.

Post-race inspection revealed that Giles had had the temerity – in the eyes of the Triumph top brass – to substitute the factory frame for that of a Victor. Worse still it had been supplied by Brian Martin – ‘the opposition’ at BSA – a ‘crime’ which resulted in John being ‘hauled over the coals’ by Edward Turner; the irate Turner telling Giles in no uncertain manner: “Do you not realise it’s an honour to ride a Triumph? In the future stick to Triumph.”

With this sort of inter-factory rivalry and small-mindedness it’s perhaps not a surprise to learn that the idea of producing factory TriBSAs was not met with wild enthusiasm – certainly not by either factory’s management hierarchy, although understandably Triumph’s riders were cock-a-hoop. By this time Triumph were no longer making off-road competition bikes – the Trophy had long gone and the trials (Mountain) Cub was export only – so the prospect of getting a decent handling frame went down extremely well.

The original intention was that nine works TriBSAs would be built and the bikes, along the two factory teams, would assemble in Wales for testing and selection tests. As it transpired this proved to be a shambles as the day before the trials were due to take place, the ACU and ISDT team manager Jack Stocker were informed that only one bike was ready and even this was discovered to be ill-prepared.

From the outset numerous ‘spanners’ had been thrown into the works, not least by the BSA riders who claimed that the unit Triumph engine was too heavy and to save weight should be equipped with light alloy – instead of cast-iron – cylinder blocks. Triumph countered, saying that this would leave insufficient metal around the base of the flange studs; this was almost immediately trumped by BSA, who had cast and presented Triumph with the barrels themselves!

From the outset numerous ‘spanners’ had been thrown into the works, not least by the BSA riders who claimed that the unit Triumph engine was too heavy and to save weight should be equipped with light alloy – instead of cast-iron – cylinder blocks. Triumph countered, saying that this would leave insufficient metal around the base of the flange studs; this was almost immediately trumped by BSA, who had cast and presented Triumph with the barrels themselves!

If period anecdotes are to be believed, though, half of the 14 sets made went missing between Small Heath’s machine shop and Meriden… All of this of course is a sad reflection on two of the giants of the British motorcycle industry and by the time the International came around in September, there was still no sign of the promised nine hybrids.

Trying to accurately chart who rode what and which components they sported – especially 40 years on – is all but impossible, but what is clear is that Arthur Lampkin rode TriBSA GOB 657D and in the Vase squad his brother Alan (Sid) was mounted on GOB 655D. The rest were largely a rehash of the bikes from 1965 with engines and frames brought up to the latest Daytona specification; some were ridden by BSA personnel with Victor front wheel and forks, while most of the Meriden men had all-Triumph front ends. History records that of the 18 British Gold medallists – which included Sid Lampkin – in the 1966 ISDT, Arthur Lampkin accrued 637.74 bonus points, an achievement which saw him emerge top scorer in the six-man Trophy team.

But what happened to GOB 657D after it returned to the factory? After competing in an event like the ISDT, many factory bikes were either broken up or updated for future events but on its return to Meriden, GOB 657D was left to languish in a corner of the competition shop. What is clear is that it wasn’t used in another International Six Days as 1967 would see the major British manufacturers axe their support for the event. The manufacturers gave the reasons thus: ‘The trial no longer represented a fair test of their road machines and it had outlived its usefulness’ and added to which, ‘BSA couldn’t sell bikes behind the Iron Curtain’.

But what happened to GOB 657D after it returned to the factory? After competing in an event like the ISDT, many factory bikes were either broken up or updated for future events but on its return to Meriden, GOB 657D was left to languish in a corner of the competition shop. What is clear is that it wasn’t used in another International Six Days as 1967 would see the major British manufacturers axe their support for the event. The manufacturers gave the reasons thus: ‘The trial no longer represented a fair test of their road machines and it had outlived its usefulness’ and added to which, ‘BSA couldn’t sell bikes behind the Iron Curtain’.

The statements not only veiled the industry’s apathy, disinterest and general malaise but – after being beaten to a manufacturers’ team award in Sweden by both Triumph and Greeves – demonstrated more apparent sulking from within Small Heath. There may have been no works bikes but the factories did make the gesture of releasing their riders to compete on ‘private’ machines in Poland in 1967. This was with the proviso that the bikes be of British manufacture which immediately scuppered both the chances of ‘Johnny Foreigner’ getting his foot in the door or for the British teams from being truly competitive.

It would appear that the Lampkin bike lay unloved and untouched at Meriden until the comp shop closed in 1968, whereupon it was sold – along with his 1966 Gold medal-winning Triumph – to British ISDT team captain Ken Heanes. Four decades later Brian acquired the bike after a chance encounter with a stranger at the Netley Marsh autojumble in 2005, one which resulted in a straight swap of an early swinging arm Triumph Trophy for the rare ISDT machine. Brian takes up the story.

“I’ve since spoken to Ken (Heanes) and I understand he sold it sometime in 1970 to a chap who used it as a road bike up until 1979; this man obviously had an eye for rare and unusual machines and it sounds like he built up a juicy little stable of off-roaders. In the 16 August edition of Motorcycle News he ran an advert entitled – ‘reducing collection’ – this ad featured not only the TriBSA but a 1953 500cc Manx Norton, the ex-John Brittain ISDT Royal Enfield LWF 424 and three ex-works BSAs. These included 776 BOP – ex Smith and Sandiford – BOK 228C – ex-Scott Ellis – and a lightweight works scrambler formerly raced by Jeff Smith – all interesting stuff.

“I’ve since spoken to Ken (Heanes) and I understand he sold it sometime in 1970 to a chap who used it as a road bike up until 1979; this man obviously had an eye for rare and unusual machines and it sounds like he built up a juicy little stable of off-roaders. In the 16 August edition of Motorcycle News he ran an advert entitled – ‘reducing collection’ – this ad featured not only the TriBSA but a 1953 500cc Manx Norton, the ex-John Brittain ISDT Royal Enfield LWF 424 and three ex-works BSAs. These included 776 BOP – ex Smith and Sandiford – BOK 228C – ex-Scott Ellis – and a lightweight works scrambler formerly raced by Jeff Smith – all interesting stuff.

“There were no prices on the other bikes but the TriBSA, described as ‘an ex-works ISDT bike, needs tidying’ was bought by my friend from the Netley autojumble for £350! He’d remembered it from 1966 when it had been described in MCN as the ‘BSA Trophy’ so knew exactly what he was buying and over the ensuing years treated it to a full restoration.”

Brian is another man with a keen eye for interesting off-roaders and the works TriBSA now shares workshop space with – among others – an ex-Jim Alves Trophy and a C15 trials bike. The little BSA may not have the same provenance as the more illustrious Triumph, but it holds special memories for the man from Dorset; it’s the very bike Brian rode in the Scottish Six Days Trial in 1960 and one which, many years later, he tracked down and bought back for a princely sum of £35.

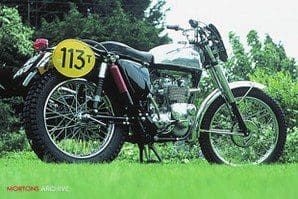

Brian is a stickler for detail and right down to Arthur Lampkin’s 113T riding number, GOB 657D mirrors its ISDT specification of September 1966. The engine sits neatly in the Victor frame although as Brian told me this ‘arranged marriage’ was not without its problems.

“It seemed a straightforward enough task but as they discovered in the Welsh three-day selection tests the exact siting of the engine in the frame was critical. Chain tension was far too slack when the dampers were extended but as tight as a banjo string when the same dampers were compressed.”

As history records, this was eventually overcome, so perhaps it’s time to look over the bike and identify where the donor parts originated.

The frame, forks and front wheel are all from the BSA Victor while Triumph’s contribution comes in the form of the engine/gearbox, swinging arm and rear wheel. With the aid of a welded-on Tommy bar this is quickly detachable, leaving the brake drum and sprocket in situ. Not a good job to be executed in mud and just to ensure the spacer wasn’t dropped and lost it’s secured by a wire, while the easily detachable speedo drive is held in position by a spring. The front brake is a straightforward single-leading shoe but as I later found out one which is extremely effective; an ingenious self centralising system doing a good job to ensure that as much of the shoe as possible is kept in contact with the drum.

The frame, forks and front wheel are all from the BSA Victor while Triumph’s contribution comes in the form of the engine/gearbox, swinging arm and rear wheel. With the aid of a welded-on Tommy bar this is quickly detachable, leaving the brake drum and sprocket in situ. Not a good job to be executed in mud and just to ensure the spacer wasn’t dropped and lost it’s secured by a wire, while the easily detachable speedo drive is held in position by a spring. The front brake is a straightforward single-leading shoe but as I later found out one which is extremely effective; an ingenious self centralising system doing a good job to ensure that as much of the shoe as possible is kept in contact with the drum.

Unlike Triumph’s normal ISDT practice of an offside, low-slung exhaust and silencer, the TriBSA features a nearside, knee-level system; while this gave the advantage of some much-needed extra ground clearance, it could be an unwelcome hand warmer in the event of having to remove the single Amal carb.

Poor preparation

Throughout the history of the ISDT many British hopes of ISDT Gold were scuppered by poor preparation but looking at GOB 657D it’s obvious that a lot of thought was given to both durability and reliability. There is no battery fitted and sparks are taken care of by an energy transfer system, the twin units kept out of the elements under the hinged seat.

Clogging or inefficient air filters often heralded the ‘waterloo’ for the Brits but the Trophy features a large capacity impregnated paper element housed inside a substantial glass fibre casing which – as the results proved – did an admirable job at keeping the mud and crud at bay. In the event of a puncture the position of the valve is marked by bright red paint, the same pillar-box colour also adorning the gas bottle which is attached to a lug welded to the rear of the frame down tube.

In an ISDT, a few seconds could be the difference between winning and losing a Gold medal and although the bike is fitted with an easy-to-use centre stand I was surprised that there was no duplication of spare cables; these I understand were carried by Arthur Lampkin in his Barbour jacket pocket.

The heart of the ‘Trophy’ is Triumph’s well tried and tested alloy barrelled twin – bored out to 502cc this features a wide ratio four-speed gearbox with a 17.1 (down from 15.1) first gear. This lower gear gave the clutch a much easier time and undoubtedly made the bike much more rideable in tight, nadgery going or where bulking occurred.

On the nearside of the bike you can’t fail to notice the huge plastic engine breather pipe which leads from the primary chaincase filler cap before venting to air. This allows pressure to escape while a bleed hole keeps the oil at the correct level. Six gruelling days of dust and mud obviously gives a drive chain a hard time so to keep it lubricated a neat drip feed is fitted: the precious lube delivered via an adjustable needle valve plumbed into the engine oil’s return pipe.

On the nearside of the bike you can’t fail to notice the huge plastic engine breather pipe which leads from the primary chaincase filler cap before venting to air. This allows pressure to escape while a bleed hole keeps the oil at the correct level. Six gruelling days of dust and mud obviously gives a drive chain a hard time so to keep it lubricated a neat drip feed is fitted: the precious lube delivered via an adjustable needle valve plumbed into the engine oil’s return pipe.

There is still some evidence of components being ‘wired on’ for the ISDT, these include the engine to the frame and also the inspection cover on the primary chaincase. This was fitted especially for the ISDT so that at scrutineering paint could be applied to the generator – a non-replaceable part – without removing the whole primary chaincase.

So does the bike perform as well as it looks? Well, as I quickly discovered from my all-too-brief ride, the answer is yes it does. There is no choke fitted but as long as the carb was well primed starting was a first kick affair. Due to the alloy barrels there was some mechanical resonance but this was soon drowned out by the exhaust note; one which can be best described as a pleasing, slightly muted rasp.

There’s no denying the engine’s flexibility and thanks to the low first gear it would trickle along at barely above walking speed with little or no snatch. The lanes of Dorset are not the place for high-speed histrionics but I’m given to believe that the wide ratio gearbox gave the TriBSA a top speed approaching 100mph; this proved by Lampkin’s stirring ISDT special test performance on the Anderstorp GP circuit.

As mentioned before the brakes are superb and allied to the sure-footed handling – not to mention the riding skills of ARC Lampkin – it’s easy to see how it came away from Sweden – its one and only event – with a Gold medal, it was – and still is – a terrific machine.