James Tennant-Eyles is used to fussy customers. It is one of the occupational hazards of a professional restorer of motor cycles, and if you can’t live with it then you get out and find a less stressful job. A fussy customer, however, does not necessarily mean one who finds fault with what you’ve done, it can mean one who insists that you and he get it absolutely right. Which is good for your reputation and makes him very happy.

One such customer is Patrick Uden, producer of television programmes and collector of Italian motor cycles. He probably has more reason to be fussy than most of us, since taking something on trust from a supposed ‘expert’ has cost him dear. In 1980 a 250cc MM51AS was featured in glorious colour in Classic Bike. Patrick fell deeply in love with it, and bought it from Moto Vecchia (which has since changed hands, so no slur is intended on that company as present constituted), where it was described as a genuine Milano-Taranto Replica (the Milano-Taranto was a long distance race through Italy, a motor cycling equivalent of the Mille Miglia). It was no such thing.

By the time the truth had been revealed (and Uden says pithily but euphemistically that the ‘restorer’ had “made a complete Horlicks of it”) Moto Vecchia had been taken over by Jack Lilley, who felt so uncomfortable with the whole affair that he sought another MM — rare even in Italy imported it and gave it to his predecessor’s customer. So Uden had two MMs, different models, neither of which could be described as an aficionados dream.

Enter James Tennant-Eyles, or rather, enter Patrick Uden into Tennant-Eyles’ manorial premises with two old motor cycles. “Make this lot into a superb MM 51AS, my man” he said in effect, “and it has to be perfect.” Naturally it was not expected that Tennant-Eyles should know what a perfect MM 51AS looked like, and Uden went to a lot of trouble to research the marque and model.

His initial contact was with Carlo Perelli, editor of Italy’s foremost motor cycling magazine Motociclismo. Perelli was able to send some photographs from the archives, and to publish Uden’s request for information in Motociclismo’s Consuela d’Epocha (Classic Advice Bureau— the Italian version of You Were Asking). From this came the best possible contact that could have been hoped for.

Mario Mazzetti, one of the Ms in MM, left his heritage to his daughter, who did not really want to know about it. Her husband, however, did. In fact Giampaulo Tozzi has made it his hobby to revitalise the MM image. He collects machines, data, reference material and anything else connected with the factory, and he was able to help Uden with drawings of obscure points of detail. He could even supply some parts. Without Tozzr s help it is doubtful that Tennant-Eyles could have done such a brilliant job.

It was fortunate that, between the two bikes supplied, most of the major components were present. Of the missing parts, the toolbox had to be made from scratch, using photographs and drawings as the pattern, and the silencer, though basically an Armours-supplied item, was highly modified. First it was cut open and shortened, and then the ‘cut-out’ (highly illegal incidentally) was made from scratch and fitted. Tennant-Eyles did the welding himself, and was less than pleased to find that the cut-out spindle had seized — fortunately it freed off again when the engine was run and the pipe warmed up.

The speedometer mounting bracket was made with the aid of a diagram from Tozzi, who also made clear the operation of the unique sliding throttle and advance-retard levers; likewise the valve-lifting mechanism was either missing (one bike) or unrepairable (the other), so a new one was fabricated. The front number plate is brand new too.

Those lovely tank transfers are not really transfers at all. Tozzi supplied the “only two left in the world” (a claim which has been heard before and doubtless will be heard again) but the backing refused to peel away from the long flashes. A cardboard template was made, using the originals as a pattern, then the gold flashes were masked out and sprayed. When they had dried black lining tape was applied and the whole lot was sealed with clear lacquer.

When it came to the engine, Tennant-Eyles described the work carried out as straightforward. Nevertheless, a new driveside mainshaft had to be turned up, splines machined out and then hardened. It was discovered that the ‘Milano-Taranto Replica’, which had the better engine, was fitted with a Honda piston which did not suit the motor or the owner or the restorer. A number of replacements were tried out before a specially machined item from Peter Hepworth was settled on. Tennant-Eyles cannot recommend the service offered by Hepworth highly enough, so impressed was he by the standard of work and helpfulness. Apart from the piston and mainshaft, the motor was reconditioned throughout, as was the gearbox, with new bushes and bearings.

‘Fussiness’ reasserted itself when it came to the chainguard. MM, it seems, fixed one end solidly and rubber mounted the other, if that was what MM did, that was how it had to be, and Mini ‘cotton reels’ (those insulating mounting studs so beloved of the racing fraternity) worked a trick.

Suspension is an interesting feature of the 51AS. The front fork design was coveted by other Italian manufacturers, including Moto Guzzi, whilst the rear end is fitted with adjustable plungers. The system is similar to the Morgan ‘sliding pillar’, with phosporbronze bushes at the top and springs either side of the axle-carrier assembly. Turning the knurled adjusters sited on the top of each plunger raises or lowers the spring preload, although there is no damping, and making sure that the sides are balanced might prove difficult.

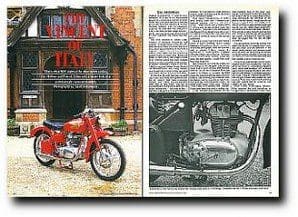

Paintwork, that lovely red which, in the opinion of many, is the only colour suitable for a motor cycle other than black, is to Tennant-Eyles’ full concours standard. This is the top-of-the-line finish, the others being standard and concours. Needless to say, the price rises with the standards, so that the customer can trim costs to a budget. A special finish is also available for alloy parts, which involves bead blasting and then clear lacquering. This helps to keep them easy to clean and, of course, preserves the alloy from corrosion.

Patrick Uden is very happy with the result, and reckons that the MM is about as original and authentic as it can be. “James TennantEyles,” he says, “has done a remarkable job.” From a fussy customer, that’s quite a compliment.

Owner’s view

Even the studious motor cycle enthusiast frowns at the red and gold components of the Italian MM. Its identity crisis isn’t helped by the distinctly British lines of the machine. The reason is that the Bologna-built singles were quite blatant attempts to offer the Italian market of the mid-fifties an AJS lookalike, although beneath the very unBritish high-grade aluminium engine castings the similarity vanishes in a forest of caged needle-roller bearings and deftly drilled oilways. Outwardly the MM that was released onto the market in 1951/2 — the MM 51AS, or Super Sport— is as typical of the period as any European machine. It’s not until a closer examination reveals the delicately made handlebar components with their precision-made sliding advance/retard and choke levers that a clue to the motor cycle’s claim to be the ‘Vincent of Italy’ starts to make a little sense. Of course the MM has none of the drama that such British machines possess, but the fastidious attention to the little things does give it something of the same aristocracy.

In straightforward descriptive terms the MM 51AS seems simple enough. A single-cylinder overhead-camshaft two-fifty, telescopic, or rather ‘teledraulic’ front forks with vertical sliding-pillar rear springs, oil tank under the saddle and magneto ignition plus battery are mainstream fitments for an Italian bike of the period. But when the engine is stripped of its smooth side-plates a pre-war engine design is revealed that was based on a 1938 racer— so much so that when MM won the prestigious Milano — Taranto road race with a modified 51AS in 1950 it was with what was to all intents and purposes a Grand Prix machine from 1938! The compact overhead cam has a Weller chain drive from a tower of gears running in a slot in the right hand crankcase and cylinder casting. Hairpin valve-springs did the rest The gearbox is driven by a single row chain from the half-speed clutch and can be adjusted for lash by rotating its cylindrical casing and locking it in position against the unit-construction crankcase. All very similar to AJS/Matchless practice, in fact later on MM were close to licencing AJS designs in Italy as their own fortunes wobbled before total collapse in 1958.

The 51AS is a delight to ride. The four gears are butter-smooth, the clutch light and the engine punchy but not at all powerful, giving the entire thing a rather stately and dignified gait unlike many of the gasping British 250cc sports motor cycles around at the time. The handling is fine and very undramatic. The brakes are like many Italian machines of the fifties, simply brilliant with stopping power well beyond the needs of the engine’s ability to propel the machine forward. Safe and sound would probably be the unfashionable summary of the contemporary test rider.

Being rare even in its native Italy the MM 51AS was never imported into Britain. One of the biggest orders the factory ever received for the 51 series was from the Bologna police force, but today a buyer would be lucky to find a complete machine anywhere in Italy. The real readim for their scarcity is that the MM factory never got back into the swing of things after the war mainly because the Mazzetti family who owned it were Jewish and had a tougher time during hostilities than other makers who could turn their talents to war production instead of being closed. So for MM the war was a catastrophe. Two of the three remaining founders of the works, Mazzetti and Alphonso Morini split up, with the latter forming his own company which could take advantage of the fast growing performance related market in post-war Italy. Mario Mazzetti, the brilliant engineer and equally poor businessman lost heart and despite the efforts of his partner and designer Dr. Salvia the enterprise fell into the shadow of the fast developing Ducati Meccanica and Moto Morini machines entering the Bologna market in the relatively regionalised Italian scene. Morini’s 1957 Rebello, being very similar to the 1956 MM Supersports, quickly showed which of the two ex-colleagues had the vision to change and it was Morini who won the day.

So the MM of 1951/2 is an odd machine. Aping larger British bikes, bearing mechanical similarities to its 1938 racing origins and yet pretending to be an advanced, forward-looking design for a hopelessly optimistic future that Mazzetti thought would hold a place for a very expensive, relatively slow, but beautifully constructed two-fifty. With, the advent of the motor scooter and the Fiat 500 light car a worse set of parameters for the design of a motor cycle would be hard to imagine. From 1952 onwards ‘S’ would stand for sport, not the pre-war sport of flat caps and tweed jackets but the clip-on and crouch sport of racing, with road going 250cc machines that would reflect the charisma, noise and impracticality of the track. View the original article.