The programme for the 1922 Olympia Show listed 310 exhibitors of one sort or another, of which no fewer than 94 were displaying complete motor cycles. All the well-known names were there, of course — BSA, Matchless, Norton; but there were shoals of makes whose names are now forgotten even among vintage enthusiasts. These included Aerolite, Alecto, Grigg, GSD, Hawker, Orbit, and Martinsyde, while Stand No. 15 was occupied by John Wallace, of Cedar Road Works, Hertford Road, Enfield Highway, Middlesex, displaying a 3½ hp single-cylinder sports model bearing the name Duzmo.

Those early ‘twenties were the formative period of British motor cycle design, during which the rather unreliable fixed-gear, belt-driven machines of pre-WW1 gradually evolved into the solidly worthy chain-driven models with which Britain led the world in the ‘thirties.

Like many of its contemporaries, the Duzmo had a short life of less than four years. By the time the 1923 Motor Cycle Show came around, the Duzmo had vanished from the market. Here, then, is the brief story of the marque, and of its designer — John Wallace, my uncle.

Born in 1896 and educated at Askes Grammar School, John was determined to be an engineer from an early age, but except for some extra mathematics in his last year at Askes he had no formal training in engineering, either theoretical or practical, and he was entirely self-taught.

It was after visiting a 1911 motor cycle exhibition that he decided to build a motor cycle for himself, from a set of unmachined castings offered at 10s. He built and equipped a small workshop in his father’s garden and began to teach himself the use of tools, but soon realised that machining thecastings was beyond both his ability and equipment.

He therefore boug ht a second-hand engine, and wheels and a frame from a local cycle maker, put together a motor cycle and subsequently sold it. At that stage, though, the local authority ordered him to pull down the workshop, which did not comply with local building regulations.

ht a second-hand engine, and wheels and a frame from a local cycle maker, put together a motor cycle and subsequently sold it. At that stage, though, the local authority ordered him to pull down the workshop, which did not comply with local building regulations.

Leaving school in the spring of 1912 he hoped to obtain an apprenticeship with Collier & Sons, makers of Matchless motor cycles. On the other hand, his father had wanted him to join the family firm of military clothing manufacturers, and only reluctantly did he agree to John serving a provisional three-month spell at Matchless.

After an accident at the factory in which John injured a leg, his father forbade any further attendance — but as some consolation he bought him and his elder brother a TT model Rudge each! Without declaring their ages, they both joined the British Motor Cycle Racing Club, and at the age of 16 John Wallace began a Brooklands racing career – regrettably with no success, and finally damaging the Rudge beyond repair.

Early in 1913 he took a job with J A. Prestwich as an experimental department test rider, the work including speed trials at Brooklands. For sonic months things went well, until the fire became aware of his tender age anc lack of engineering experience, anc gave him the sack. From then until the end of 1914 he remained at home studying engineering theory anc practising the art of the draughtsman.

Realising that nobody was going to be interested in a new motor cycle design in wartime, he took a job with Arrol-Johnston, the Scottish car makers, working on aero-engine design. By this time he was an excellent draughtsman, but lack of experience told against him, and by mid-1915 he was again out of work.

However, as the war progressed so aeroplane manufacture expanded rapidly. Anyone with the least experience in engineering drawing was needed urgently, so in 1916 he joined the design staff of the Westland Aircraft Company (Petters Ltd) and there he remained for the rest of the war.

Leaving Westlands at the end of 1918, he began the design of a high-performance motor cycle engine, and offered this design through an advertisement in The Aeroplane to any firm looking for fresh fields of activity to take the place of the now-defunct military contracts.

The advertisement was answered by a small firm located at Enfield, known as the Portable Tool & Engineering Company. They had been producing shell components, but with the end of the war the directors had to decide whether to sell up and share the liquid assets, or embark on some new venture. They decided on the latter course, and a meeting with John Wallace was arranged.

The first idea was to produce an engine only, and market this for other manufacturers to fit to their machines. Although only 23 years old, John Wallace was appointed Chief Engineer and Designer, and in September 1919 the first engine was ready for trials.

At this critical stage an old Brooklands racing friend appeared, and offered his services to John for a modest salary. This was none other than Bert Le Vack, who had spent the war building and testing aero engines. Le Vack was a mechanical genius who could take an assembly of ill-made parts, and by painstaking filing, scraping, and general titivation turn it into an efficient mechanism.

His first job was to get the prototype engine running satisfactorily on the bench. After that a second engine was built, to be installed in a motor cycl e frame, and Le Vack was to ride this machine in competitions, and demonstrate it to the trade and general public.

e frame, and Le Vack was to ride this machine in competitions, and demonstrate it to the trade and general public.

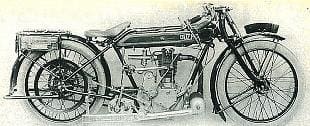

Wallace by now was a first-class designer, and the combination of his design and Le Vack’s expertise resulted in a formidable machine. At first known as the Ace, then rather unfortunately, as the Buzmo, the machine had adopted the Duzmo name (“It duz mo’ miles an hour!”) by 1920, during which racing season Bert Le Vack became very prominent.

Track success had two very important results. First, orders for the Duzmo poured into the office at a rate grossly beyond the manufacturing resources of the company, and secondly Le Vack attracted the attention of larger and more powerful manufacturers and was soon made an offer (by JAP) beyond anything possible at Enfield Highway.

Although the intention had been to offer the engine as a proprietary product, the vast majority of orders were for the complete bike, as ridden by Le Vack. That was beyond the capacity of the small works at Enfield, and it was decided to float a public company and expand the organisation to cope with the bulging order book. Easier said than done, and after some delay the Portable Tool directors, unable to raise the finance, decided to wind up the company.

This was a bitter blow to Wallace, but one of the directors suggested that he should take over the assets of the company and run it himself; the same director offered to advance the purchase money, repayment to be made from the expected profits. Agreement was reached, and thenceforward Duzmo machines were made by John Wallace trading under his own name.

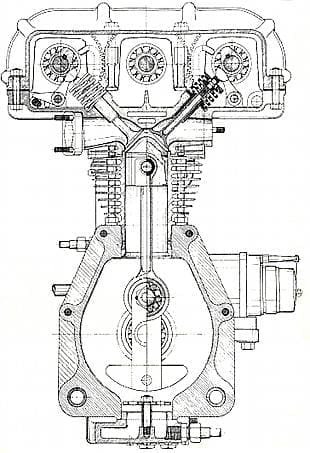

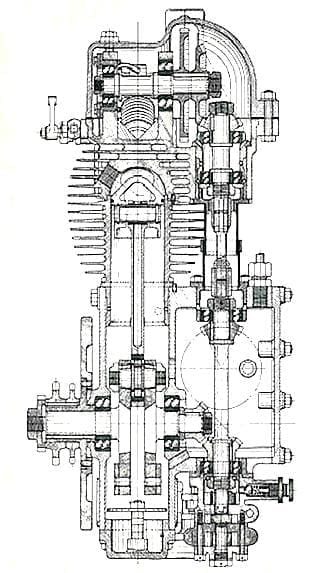

The original Duzmo was a direct belt-driven 496cc which entered production in 1920 in a more refined form, engine manufacture being largely undertaken on contract by Advance Motor Manufacturing Company of Northampton, themselves motor cycle makers in pre-WW1 days.

More modifications were made during 1921, and for the 1922 season the 496cc adopted a Sturmey-Archer gearbox and all-chain drive. Wallace doubled this up to make a 992cc veetwin, but only one machine was ever made and, fitted with a sidecar, this took part in the Brooklands 200-Mile Sidecar Race.

Bert Le Vack had left soon after Wallace took over the company, and from then on Wallace raced the Duzmo himself. But though he was a brilliant and original designer he lacked Le Vack’s expertise as a mechanic and rider. He achieved little success in racing and this, combined with worsening economic conditions, led to a drying-up of new orders in 1922.

In addition, John Wallace was no businessman. He was to design one more version of the Duzmo — a sloper,with lowered seating position — but only one was built before Wallace went bankrupt in 1923. Although he never worked again in the motor cycle field, his interest continued for some years and he produced design studies for a very handsome overhead-camshaft single, a straight-eight two-stroke, and a seven-cylinder radial.

Also, he made a mathematical study of the phenomenon known as wheel wobble, and in November 1930 published a long paper in the proceedings of the Institution of Automobile Engineers (of which he was an associate member) on ‘The Super Sports Motor Cycle’, which included an appendix on steering layout. A year later he delivered a lecture to the Institution of Automobile Engineers, meeting in Woverhampton, on ‘Multi-cylinder engines as applied to the Motor Cycle’.

At that period there were, as  there are today, many terrace-type houses which presented parking difficulties for anything more than a pushbike or solo motor cycle. Wallace produced a preliminary design for a tandem-seated cyclecar based on his aircraft experience. Narrow enough to be taken through the average front door, it was similar to the post-war Messerschmitt bubble car — though without the ‘bubble’, for motor cyclists and sidecar passengers of the time did not expect much protection from the elements.

there are today, many terrace-type houses which presented parking difficulties for anything more than a pushbike or solo motor cycle. Wallace produced a preliminary design for a tandem-seated cyclecar based on his aircraft experience. Narrow enough to be taken through the average front door, it was similar to the post-war Messerschmitt bubble car — though without the ‘bubble’, for motor cyclists and sidecar passengers of the time did not expect much protection from the elements.

Unable to obtain backing for any of his ideas, he lost interest in the motor cycle and its derivatives. By then, anyway, he was a design draughtsman with D. Napier & Sons, the aeroengine makers, and when he retired in the 1960s he was their Chief Test Plant Engineer. He died in October, 1983, at the age of 87.

There were many factors contributing to the decline of the British motor cycle industry in recent years. An important one was that it was no longer attracting innovative designers of the calibre of P. J. Wallace. View original article