Summer 1984. Yours truly has just passed his bike test and bought a (well) used Suzuki GT380. Convinced that this old smoker is the fastest thing on the planet (in my world nothing could possibly go any quicker than this) I spent a week or two challenging anyone to a race.

Most spared my blushes, but Brendan, a mate of a mate, said yes.

Brendan had a brand new GPz900R and the following few seconds remain some of the most memorable in 27 years of biking. That bike was so much faster than my ‘fastest-thing-in-the-universe’ that I almost cried.

Kawasaki’s GPz900R deserves its legend status. Rarely does a bike move motorcycling on so far so quickly. Back in that summer of 1984, nothing could catch this Kawasaki.

The early 1980s were important times for motorcycling. As Triumph (and with it, the last of the British bike industry) finally toppled over, the Japanese, with pockets stuffed full of R&D cash fought like crazy for two-wheeled technological supremacy. Anything went and the next few years would see imagination and innovation not seen since the early days of motorcycling.

Frame tubes became square, not round and the aluminium revolution was coming. Spine frames, cradles and twin spar beam units fought for dominance – it was 1989 before everyone agreed that a beam was best for handling, styling, weight distribution and packaging.

Frame tubes became square, not round and the aluminium revolution was coming. Spine frames, cradles and twin spar beam units fought for dominance – it was 1989 before everyone agreed that a beam was best for handling, styling, weight distribution and packaging.

Suspension and brakes were getting bigger and beefier. By 1983 we had to understand damping adjustment. 16in wheels were famous for five minutes and Honda’s 1984 VF1000R was the first production bike with radial tyres.

Engines were inline, parallel or vees. Two strokes spouted power valves while the four strokes now had at least four (sometimes five) valves per cylinder. Turbos were famous for less time than teeny front wheels and Yamaha gave us V-Boost – two carbs feeding each cylinder – on the mighty V-Max.

By the late 80s it was over. Most manufacturers settled on 16 valves, inline engines, beam frames, 17in wheels and adjustable suspension. There were still occasional visionaries (mostly Yamaha) but from 1990 on it was mostly about more power, more revs, more adjustment, less weight and sidestepping the emissions laws.

The GPz900R lasted 13 years, transforming from ultimate hyperbike to 150mph sports tourer in the process. In 1984 no one could catch this Kawasaki, 25 years on, there’s never been a better time to buy one. Here are 25 things every GPZ900R owner should know…

01 It predicted the Fireblade and the future of Japanese sports bikes

In 1983 the best sports bikes were the biggest, heaviest and fastest in a straight line. Kawasaki turned the world on its head by building an engine with 20 per cent less capacity, making similar power from more revs and putting it in a lightweight, short chassis that redefined handling and roadholding. Eight years later Honda’s FireBlade did the same thing. Although the Blade didn’t make that much more power than the GPZ, it made more midrange and weighed 49kg (that’s a whole Dani Pedrosa) less than the Kawasaki.

02 It was the first 150mph superbike

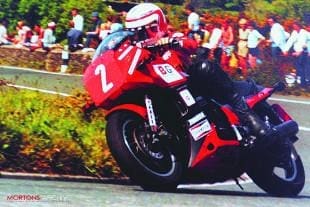

By a whisker. 1984 was the year when bikes got faster. Yamaha’s FJ1100 was close, as was the RD500 but the GPZ was first. It also had a clean sweep in the 1984 TT production class. The only bikes that could get close to the GPZ all had at least 20 per cent more engine capacity.

03 It was the first Japanese superbike to really handle

Short wheelbase, light weight and state-of-the-art (in 1984) suspension plus a new spine frame that used the engine as a stressed member for extra rigidity and light weight.

04 It inspired the Hinckley Triumphs

Triumph were smart. When the Leicester firm first started planning the Trumpet revival they looked at who was making powerful, reliable and easy-to-use engines. Those first Triumph motors shared a lot of thinking with the GPZ900 as did the modular range’s spine frame.

05 It made Tom Cruise cool

Even though the bike he rode in Top Gun was actually a GPZ750R.

06 It was the only credible superbike for the LC generation

For all those riders who’d grown up on LCs, couldn’t afford an RD500 and would never go back to an antique airhead motor (and definitely never buy a Honda), the GPZ had the cred.

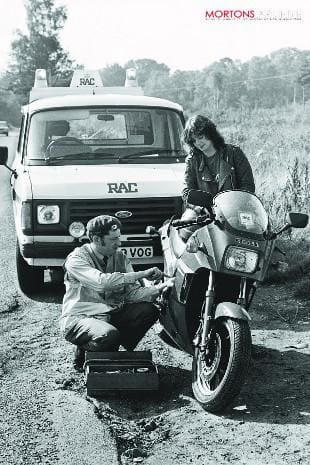

07 It made hot summers interesting

Sitting in traffic watching the temperature gauge rising, waiting for the fan to cut in. And waiting. Did your bike have ‘the resistor’ fitted? Most owners just fitted a manual switch for the fan instead.

08 And cold, damp days even worse. The GPZ was the first bike to carb ice

08 And cold, damp days even worse. The GPZ was the first bike to carb ice

Refusing to idle, running rough on small throttle openings and stalling on over-run. Kawasaki fitted carb heater kits but the problems persisted. Some blamed fuel quality and you can help matters with a fuel additive like Silkolene Pro-FST.

09 It bred a generation of quick-draw choke operators

0-6000rpm in half a second. Who remembers Kawasaki chokes? No wonder the cams pitted. Two weeks with a GPZ and you could fine tune a choke almost before the engine had caught.

10 Those cam problems were almost as bad as Honda’s

But somehow Kawasaki got away with it. Probably because it was only one model and sorted under warranty.

11 It came back from the dead

Kawasaki officially ditched the GPZ in 1995 but then brought it back a year later, finally dropping it in 1997.

12 It killed off Honda’s V-four superbikes

Even the top-of the range VF1000R suddenly seemed overweight and sluggish next to the GPZ.

13 It outlived its successor

The cruelly under-rated GPZ1000RX was a great bike but somehow managed to be no faster, heavier and slightly clumsier than the 900. It made way for the ZX10 in 1988 while the 900R stayed in the range

14 And the one after that

The ZX10 was a very different bike. Much sportier, faster, lighter and better than the 900 by every measure bar comfort. But by 1990 the ZX10 was gone too, replaced by the ZZ-R1100, while the 900 stayed in the range.

15 It was never called a Ninja

At least not in the UK. In America it seemed that even your local dealer’s dog got called Ninja, but in Britain the first bike to carry the name was the 1994 ZX-9R.

16 It was the last time a steel frame was state of the art

By 1985, if you didn’t have alloy you weren’t worth a mention. Nonetheless, the tubular steel frame proved ground-breaking technology, allowing the GPZ to mount its engine lower. The centre of gravity was naturally lower, which enhanced the bike’s handling and stability, without compromising ground clearance.

17 It was the first modern superbike

17 It was the first modern superbike

1984-88 was when Japan perfected the sportsbike. GPZs, GSX-Rs, VFRs, CBRs and FZRs evolved fast. Honda had been ambitious in the early 80s but Kawaski with the GPZ was the first one to get it right.

The progress was mainly in the engine. Compact, light and powerful. 100bhp or more depending on whose dyno you used. Water cooling wasn’t new nor were 4v heads but the GPZ was first with both in an inline design. Putting the camchain on the end of the engine helped to keep it narrow.

Bore and stroke were light years away from the old Z900’s 66 x 66mm. The GPZ had a 72mm bore (for the bigger valve area required) and (very) short 55mm stroke. Interestingly, even Honda’s 900cc FireBlade some eight years later had a longer stroke than the GPZ.

18 It was the first six-speed superbike

That short stroke engine was fast but not torquey with a pronounced power step at 8000rpm. Fitting a six-speed box helped riders keep the GPZ in the power. It took Honda three years to fit a six speeder to the CBR1000. Suzuki and Yamaha didn’t do it till 1994 (RF900) and 1998 (YZF-R1) respectively.

19 It was the first sports tourer

Don’t listen to the FJ1100 owners, their definition of sporty was different to Kawasaki’s. And by the time the big K revised the GPZ in 1989, swapping the front wheel for a 17-incher and adding a touch more midrange (they also fitted four-piston front brakes and lost the anti-dive at the same time), the GPZ became even better.

20 They’re built to last

20 They’re built to last

Cam-pitting aside, the engines are strong. And the chassis lasts well too, so long as you remember to grease the suspension linkages and understand that the anti-dive will seize on a regular basis.

22 It’s still a great bike to own and ride

And you still see plenty being ridden. GPZs are at that perfect classic place – new enough to still be special, old enough to be stupidly cheap. £1000 buys a decent, original bike that’ll scratch all summer and hack through winter.

23 It predicted modern suspension adjustment

Kawasaki’s AVDS anti-dive system worked well when new but seized all too quickly, meaning most former owners don’t miss it. But anti-dive was the first realisation that adjustable suspension control was both desirable and possible. Six years later we had adjustable compression damping which did the same job as anti-dive but with more control.

24 It overshadowed Yamaha’s RD500

Yamaha’s V4 GP replica should have been the bike of 1984, no question. But it wasn’t because the RD over promised, cost a fortune and didn’t quite deliver the full Kenny Roberts’ experience, where the GPZ delivered its promise for £3999

25 And turbos

The early 80s saw a Japanese turbo frenzy. The power of a 750 from a 650 engine. ‘Hurrah’. Kawasaki’s own GPZ750 Turbo (also launched in 1984) was the best of the bunch, but the GPZ900R was faster, easier to ride and used less fuel.

The best known GPZ900

The best known GPZ900

If you were asked to name the most famous GPZ900 of all time, chances are you’d say it’s the one ridden by Tom Cruise in the 80s epic, Top Gun. However, you’d be wrong; Tom was pictured riding the 750cc version.

You may be surprised to know that the best known GPZ900 actually resides a little closer to home, Plymouth to be precise.

In late 1983, Mike Grainger of GT Motorcycles in Plymouth received a phone call from Manchester based bike tuner, Barry Gannon. The long and short of the call was Barry wanted Mike to provide TT racer, Geoff Johnson, with a Honda VF1000RR for the 1984 production TT.

Being a solus Kawasaki dealer, Mike was unable to supply a Honda, but offered to lend Geoff one of the all new Kawasaki GPZ900s that were to arrive in the UK at the start of the New Year. A deal was agreed and when the new GPZ hit the shores in May of 1984, Mike registered a bike and clocked up 1000 miles on the road in a bid to help run it in ahead of the TT.

The bike was shipped off to Barry Gannon and prepped to the production rules. In a clever, yet legal modification to the bike, the concentric was turned around on the rear wheel in order to gain the bike more rear ride height. The tyres were changed to 150/18 profile Metzelers, which also helped raise ride height, while giving the bike a smaller contact patch in a straight line; saving fuel, reducing friction and increasing the gearing. The bike was ready and so was Geoff, even though he’d not had chance to practice on the machine. A number of the new GPZ900s had been entered into the production class and they were taking the island by storm, topping the time sheets and blowing the opposition out of the water during practice week.

Geoff had started racing the TT in 1981, proving himself to be a real contender, although he had never taken a win at the event. Confident with the package underneath him, there was no better a time for Geoff to pursue that elusive victory. With the start of the 1984 Production TT under way, history was being made as Geoff scrapped his way to the head of the field, battling off challenges from fellow GPZ mounted Barry Woodland, while the likes of Steve Parrish and Mick Grant trailed the leaders.

Geoff had started racing the TT in 1981, proving himself to be a real contender, although he had never taken a win at the event. Confident with the package underneath him, there was no better a time for Geoff to pursue that elusive victory. With the start of the 1984 Production TT under way, history was being made as Geoff scrapped his way to the head of the field, battling off challenges from fellow GPZ mounted Barry Woodland, while the likes of Steve Parrish and Mick Grant trailed the leaders.

Geoff managed to hammer home a convincing win over the three-lap-affair, with Barry Woodland finishing second and Howard Selby, who was also racing a GPZ, completing the podium. Following examination in Parc Ferme, Barry Woodland’s Kawasaki was discovered to be illegal and disqualified from the results, promoting Honda rider, Peter Linden, up into third place. Despite all this, Kawasaki still had plenty of reason to party, as Jack Gow had been promoted up to fifth, meaning they still had three GPZ finishers inside the top five.

Returning from the TT, Geoff had become a Kawasaki treasure, beating off the opposition on his privately entered machine and marking a real milestone for the newly launched GPZ. The bike was returned back to Mike who continued to use it on the roads for several years, as well as in a number of sprinting events. Unfortunately, Geoff Johnson passed away as a result of an embolism in the winter of 1991, but his legend lives on. His TT winning machine resides in the GT Motorcycles Plymouth showroom, in the named ‘legends’ café.