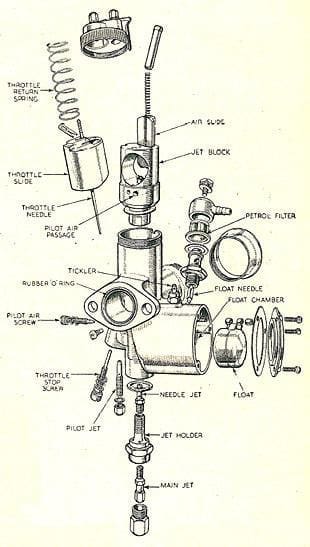

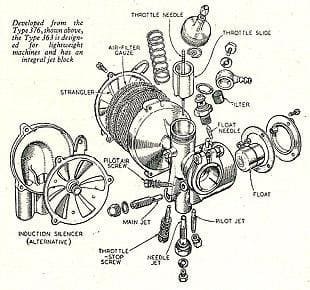

Introduced in 1954, the Amal Monobloc carburettor has been steadily developed into the ultra-reliable instrument today fitted to the majority of British motor cycles. Variations on the well-known larger Monobloc are designed for smaller machines, but whatever the external appearance the working principle is the same.

Apart from cleaning, your Monobloc requires little attention, but the economy-conscious owner who is prepared to sacrifice a small part of his machine’s performance in the search for more m.p.g. will find the four-stage operation well-suited to his needs.

Tuning for economy is a simple proposition but, in common with most things, care should be exercised not to overdo matters. More m.p.g. at the expense of a damaged machine is false economy, indeed! So before tuning is attempted it is essential to know the four phases of the Monobloc’s operation. These four clearly defined stages…

Tuning for economy is a simple proposition but, in common with most things, care should be exercised not to overdo matters. More m.p.g. at the expense of a damaged machine is false economy, indeed! So before tuning is attempted it is essential to know the four phases of the Monobloc’s operation. These four clearly defined stages…

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

Slow running depends on the setting of the pilot air screw which, regardless of pilot-jet size, controls the mixture strength to one-eighth throttle opening. Screwed in, it restricts an air passage and so enriches the mixture; unscrewed, it has a weakening effect.

Tests carried out by The Motor Cycle staffmen underlined the importance of correct setting with gains of between 10 and 22 mpg! And this setting is easy to achieve. When the engine is warm, it should tick over slowly and reliably. Too weak a setting will result in spitting back or a power ‘lag’ when the throttle is snapped open. Hunting – erratic running – or, with two-strokes, excessive four-stroking, indicates richness of the pilot mixture.

Throttle-slide cutaway height, which governs the amount of air passing into the carburettor, takes over control of the mixture between one-eighth and one-quarter throttle opening. The greater the cutaway, the weaker the mixture. Little advantage, economy-wise, will be gained from altering the cutaway, and in the main it is as well to stick with the maker’s recommendation.

The throttle slide is guided internally by the jet block and in time is liable to wear, which will be shown by erratic running and lack of response at small throttle openings, indicating weak mixture.

Throttle needle position controls the greatest range of throttle opening—from one-quarter to three-quarters. Attached to the throttle slide by a spring clip, the needle tapers towards its lower end, which is located in the needle jet and so meters the flow of fuel through the jet. When the needle is raised, the taper takes effect and allows more fuel to pass, consequently enriching the mixture.

Normally the spring clip engages in the middle one of five grooves in the needle. In the interest of economy it is generally permissible to lower the needle by one notch, thus weakening the mixture. Remember, though, that where two-strokes are concerned, restricting the petroil supply also reduces the amount of oil delivered to the engine, so that too low a setting could mean oil starvation and possibly even piston seizure. Wear of the stainless-steel needle is unlikely, but the needle jet will wear over a period of time, resulting in increased fuel consumption. The simple solution is to replace the jet.

Normally the spring clip engages in the middle one of five grooves in the needle. In the interest of economy it is generally permissible to lower the needle by one notch, thus weakening the mixture. Remember, though, that where two-strokes are concerned, restricting the petroil supply also reduces the amount of oil delivered to the engine, so that too low a setting could mean oil starvation and possibly even piston seizure. Wear of the stainless-steel needle is unlikely, but the needle jet will wear over a period of time, resulting in increased fuel consumption. The simple solution is to replace the jet.

The main jet comes into the picture only above three-quarters throttle. A rider seeking the best m.p.g. will rarely bring the main jet into play – except, of course, in the case of very small machines. Too large a main jet will give a ‘heavy’ effect to the engine; too small a jet is indicated by an apparent gain in power when the throttle is slightly closed from full-out.

Unless such symptoms are present, fitting a smaller jet, thereby weakening the mixture, can result in overheating – and again in subsequent seizure. View original article