For a few fabulous years the go-to, guaranteed-to-win bike for scrambles the world over was BSA’s Gold Star.

Words and pics: Tim Britton Media Ltd

To define what a Gold Star actually is takes a bit of doing… to some it is a trials bike, to others a road racer, still others recall in awe its legendary 70mph in first gear folklore. So is it a roadster, racer, dirt bike or what? The answer is yes, it is all of those and more as it helped British teams win gold medals in the ISDT, trounced the opposition at Daytona and won American flat-track races. The simple truth is BSA’s Gold Star is the ultimate sporting motorcycle of its era. The Goldie was a machine which could turn its wheels to any discipline and with some degree of success though the actual results often depended on who was riding it.

BSA played to this multi-use role of its sports machine and provided a comprehensive range of accessories to help owners convert their own bikes to compete in different disciplines. In practice it would have been unlikely for a private owner to have every accessory BSA produced for the Goldie but theoretically it was possible: expensive but possible.

Though BSA produced the Gold Star from 1938, the story of scrambles success begins much later with the BB version introduced for 1953. This model is the one which debuted the swinging-arm frame emerging from Irish legend Billy Nicholson’s work. Nicholson’s rise in motorcycling was stratospheric. He’d never ridden a motorcycle until the late Thirties; then by the late Forties he was part of BSA’s team and forging ahead with his own ideas on how a motorcycle should be. Fast forwarding considerably, Nicholson knew the idea a scrambler should have a rigid rear end was way off the mark. He’d been winning on his own BSA fitted with McCandless rear suspension prior to taking up a position at the factory. He designed a lightweight rigid frame for his trials bike and made it so a swinging arm rear section could be fitted. This is where the Goldie scrambles legend begins and it wasn’t long before anyone who wanted to do any winning had to have a Gold Star. This model’s frame went on to the end of the line… at least once the steering head had a strengthening gusset added. Engine development continued until the BB became the CD, then the DB and finally the DBD big fin type arrived in 1956. The Gold Star would remain in BSA’s range until 1963 but really its time was over long before then.

When the idea of classic racing emerged, it was so owners of bikes like the Gold Star and Matchless G80s could get them out and use them as they should. But one of the problems was getting hold of a scrambler. As far as BSA’s sporting single was concerned its multi-use role and ease of conversion between specifications possibly worked against it. With enthusiasts wanting to experience the Clubman Gold Star a lot of scramblers had their proper tyres and handlebars replaced by road rubber and clip-on handlebars. Still, this isn’t too great a problem as the B31/B33 single frame is an all-welded one and differs from the Goldie version by having a few more lugs welded to it. These are easily removed and the path to a Goldie scrambler is set.

Just such a path was used by Lincolnshire enthusiast Harold Allen to build this Gold Star, ably handled on the track by his lad, former grass track champion Micky Allen, who was persuaded to the classic side after retiring from modern MX. Says Harold: “I’ve built the bike from parts; some I had, others I’ve acquired, and it is 99.9% pre60 and 98% BSA.” What Harold started with was a standard roadster single frame which was carefully cleaned up to save a little weight and modded in light of experience with Gold Stars. “I pay particular attention to the chain line so it doesn’t become stressed at any point on the suspension travel,” he tells us, “and having MoT’d any number of B31/B33 roadsters here at the garage the number of twisted swinging arms on these models is eye-opening.” True to form, the swinging arm was twisted on this frame and was straightened before braces were added to it for extra strength. Connecting the rear of the swinging arm to the frame are Ohlins rear units set up to suit Micky’s riding style.

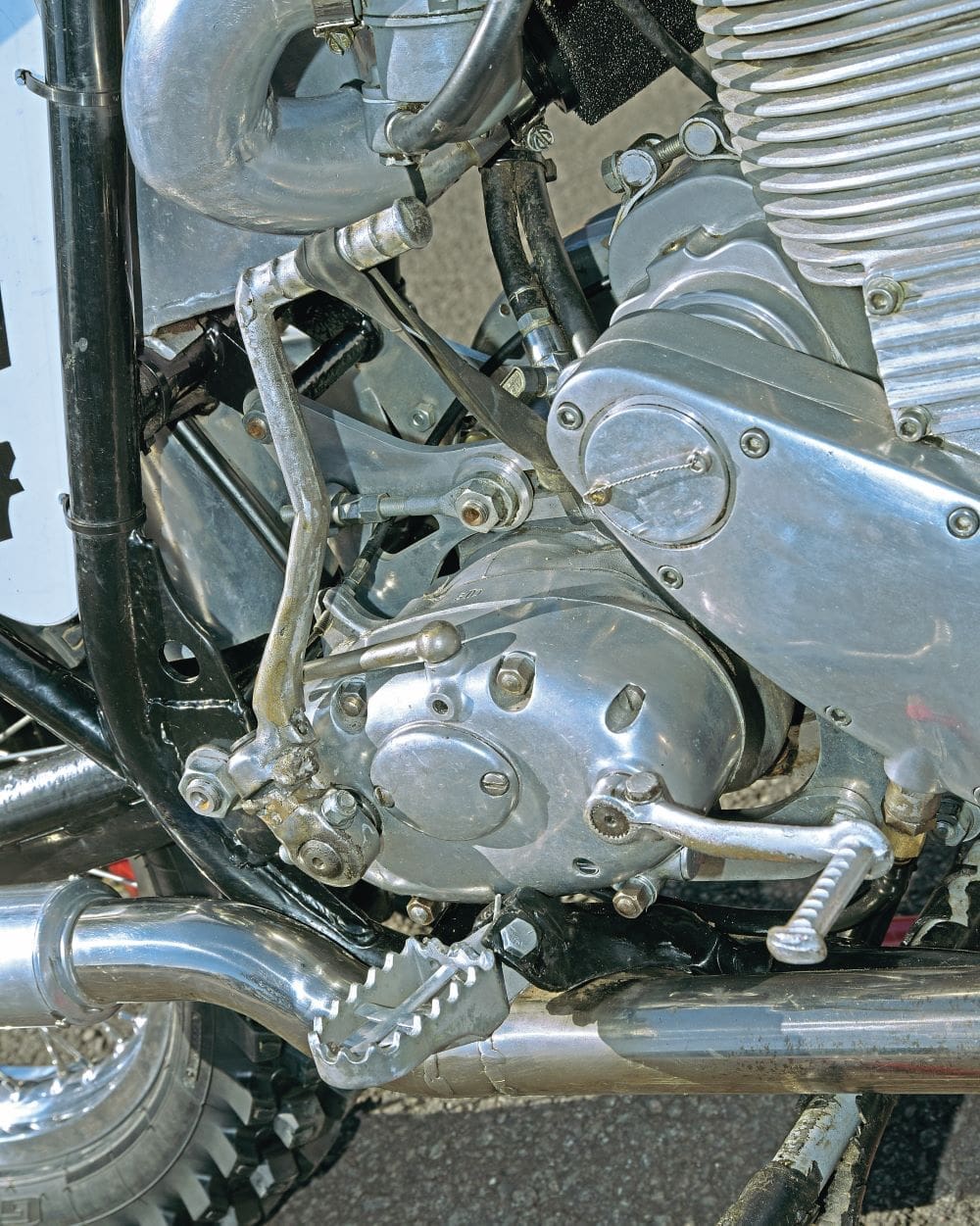

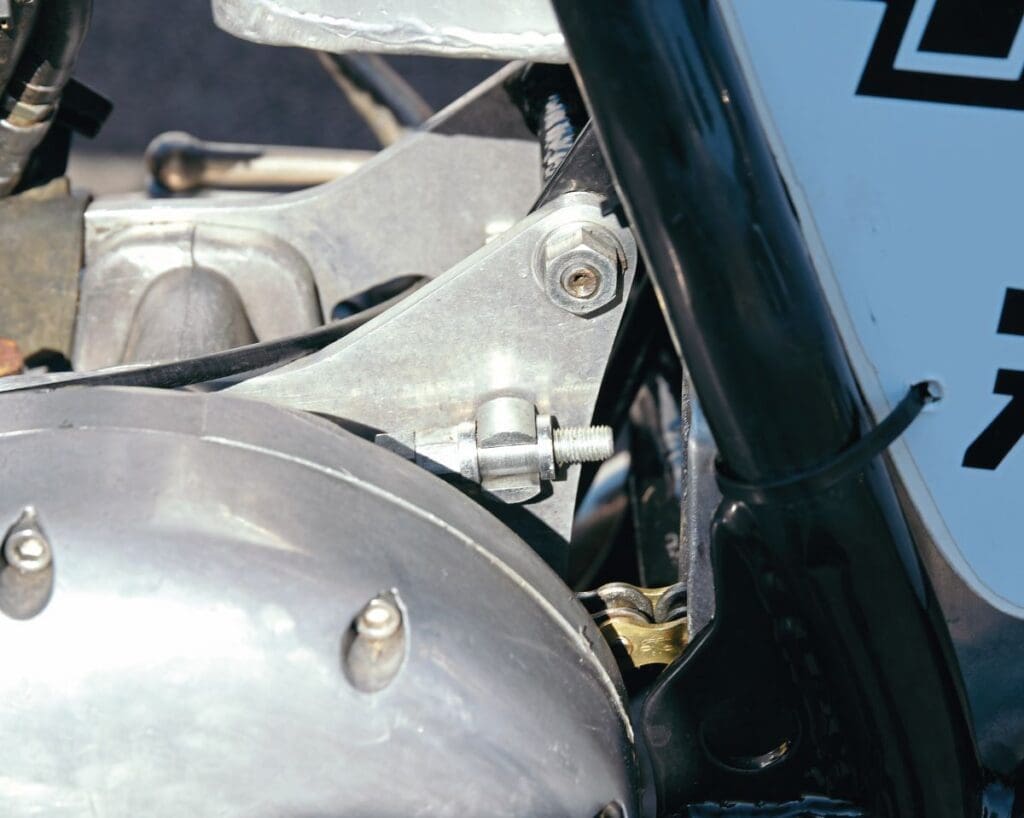

At the other end of the bike sit typical BSA A/B group fork yokes which will take a 35mm diameter stanchion fork from something a bit more modern in the suspension world. These modern forks are slipped into Norton Roadholder sliders, which is pretty much what most people do with this type of motorcycle. BSA would have used cup and cone ball bearings to control the movement of the yokes but, as Harold points out, they’re not really up to the stresses and strains of scrambling and SRM supplies a taper roller steering head kit which does the job. These last couple of sentences have glibly glossed over the amount of effort needed to make such suspension work properly but the attention to detail is needed and pays off too as the front suspension works loads better than the original, yet still looks period.

There are certain parts which have become almost compulsory when tackling a build such as this Goldie. They could be classed as fashionable but in the case of BSA’s qd ‘crinkle’ rear hub they’re popular because they work. The idea behind them is a two-part hub connected by a cog. Removal of the main spindle leaves the chain and brake equipment in place and the wheel comes out. This vastly speeds up the process in the event of a puncture, for example. There are several variations on the theme and the first one joined the range in the late Forties and it was still an option by the Seventies. Triumph used them on its 1973 ISDT machines, for example, this one on the Allen Goldie is from a B25 and has been lightened considerably. When such a hub is laced to an alloy rim it means the wheel is a lot lighter than a standard Goldie.

Up at the front end is a wheel built around a 7in diameter Grimeca full-width hub. Of light alloy casting, these hubs were standard fitment on a number of smaller Italian bikes such as Ducati and Morini in the Fifties and the Manchester manufacturer Dot also used them. Initial experiments with these admittedly light hubs proved the bearings were not quite up to the job of being on the front end of a big MXer. After some thought the bearing recesses were bored deeper and now the hub has two bearings on either side which to all intents and purposes has solved the problem. As with the rear wheel this hub too wears an alloy rim and both brake plates carry new shoes.

It is 60 years since the Goldie disappeared from BSA’s range yet development by enthusiasts and engineers continued. Eric Cheney, for instance, carried on with the big single and his rider Jerry Scott was very rapid indeed on the Cheney Gold Star. So it is safe to make an assumption there have been a few developments in the engine department during the intervening years. One of the biggest problems in using a Goldie hard is the crank; the original ones were riveted together and these rivets can fail with disastrous results. As part of our Iconic Engines series in issue 31 we looked closely at the Gold Star engine and back then we learnt there are more modern cranks available which take advantage of modern metals and manufacturing techniques. Without giving race secrets away, Harold told us the crank is a Phil Pearson one which uses a GM speedway engine con rod to carry a Wiseco piston. Originally BSA used an 85mm bore with an 88mm stroke to produce a 499cc capacity but in this engine both dimensions have been increased slightly and the engine is now at 604cc. Above the barrel things are more standard as the cylinder head and its valves are BSA… though the valve springs are Porsche. BSA provided a series of cams for all variants of Gold Star to allow the owner to dial in cam timing to suit whatever application the machine was being used for and in the spares list are Touring, Clubman, Racing and Scrambles… the latter being fitted to this bike. “There’s not too much special about the engine but it is very well put together,” he smiles.

As with cams so it is with gearbox ratios and BSA provided a cluster for every application expected for the Goldie and, in order to keep track of what was what, the legend was stamped on the gearbox casting. On this gearbox there is ‘STD’ for ‘Standard’ marked on the top of the inner cover casting. On the subject of gearboxes, Harold said: “The biggest problem for building a gearbox is getting hold of a decent layshaft, the other gears and mainshaft are much less of a problem to source.” Once all the gears are checked and approved it is a simple task of carefully building the box. “We do make a slight modification to the selector cam plate so it can be reversed to change the way gears are selected.”

As the engine and gearbox are separate entities in a Gold Star the primary case has both inner and outer components. Harold has used some old and damaged cases for the primary drive on this bike. “I don’t mind using fewer good bits and pieces and am happy to bother on and repair such things so they can be saved rather than just buy new ones.” Though to standard BSA appearance the primary cases contain something a bit more hi-tech than a single row primary chain and BSA multi-plate clutch… Inside is a belt-drive kit from Bob Newby Racing. More closely associated with road racing, Newby’s kits can also be supplied for scramblers. Says Harold: “We use a small pulley on the crankshaft and have only ever had one problem with a belt when some grit got in between it and the pulley and damaged it.” He explains this was when they were using a primary shield rather than proper cases.

Looking at the rest of the bike it does resemble the actual period machines which were racing in the Fifties, an image helped by the two-gallon alloy tank. In the Fifties and Sixties these tanks were made under the Lyta name and, in the same way all vacuum cleaners get called hoovers but not all of them are actually made by Hoover, so not all tanks to this style are actually Lyta. As they are alloy such tanks need mounting carefully or they’ll be dented and leaking very quickly. Also alloy is the oil tank which was created in the Allens’ workshop and made to fit the space where BSA’s standard tank would sit. With most of it tucked under the seat there’s only the front bit peeking out from the frame tube and this bit has a scallop in it to take the unusual air inlet tract. This is also an ‘Allen’ bit which connects on to the rear of the massive 34mm Amal Concentric then comes round in a loop and has the filter in the space between the engine and oil tank.

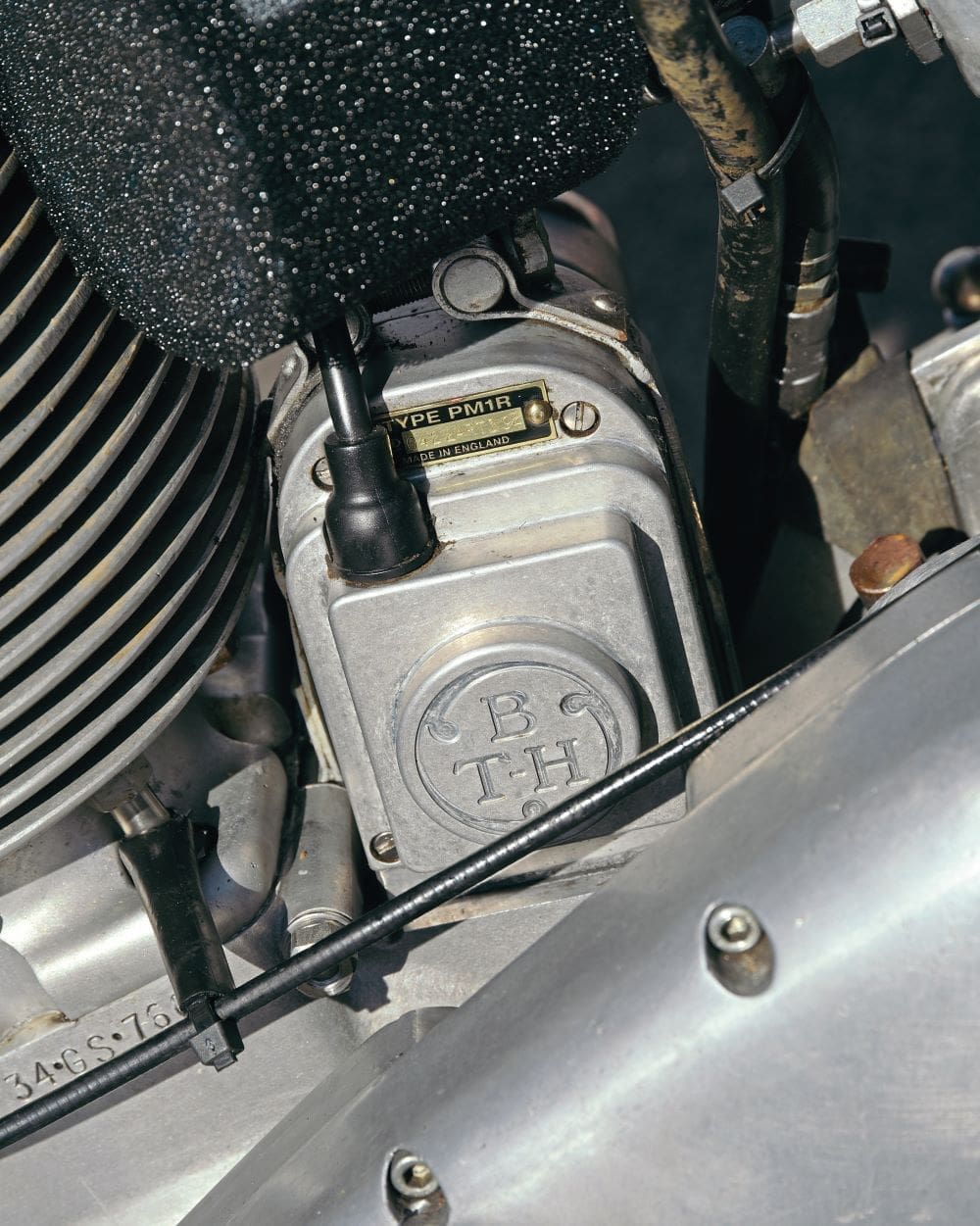

When new, the DBD Goldie scrambler our feature machine is based on was fitted with an Amal Monobloc carb which was mostly okay but under heavy use could empty the float bowl faster than the fuel flow could fill it. Available as an option was the GP carburettor which didn’t suffer fuel filling issues but needed care in assembly. A lot less fussy than the originals is Amal’s Concentric; they are available new and have a full range of spares listed. This one feeds super unleaded, with a bit of Avgas mixed in, into the engine where a spark plug fired by a BTH electronic magneto provides the bank and powers the engine.

As we chatted about this Goldie, Harold pointed out a few salient points such as the home-made seat and added the cables are all made by him. “We could have gone more modern with things like plastic mudguards but in the day it would have been aluminium mudguards so we used the same type. But I will allow we’ve gone modern on the handlebars, they’re Renthals and we’ve got Italian Domino levers with a Venhill throttle.” I wondered about the type of fasteners used on the build and found Mr Allen senior is not a fan of stainless steel. “I prefer to go along to an engineering supplier and get some high-tensile fasteners from them. There are never any problems with such fasteners whereas stainless steel might look nice but soon wilts under scrambling pressure.”

The resulting machine looks very nice and goes as well as it looks too with results to prove it, as Micky is 2024 pre60 scrambles champion and was also 2022 champ.

We know you’re going to ask what happened in 2023 and we’ll let Mick answer as he popped out on a tea-break from running the garage… “I didn’t do the 2023 series,” he says.

Earning the name

BSA began adding the ‘star’ tag to its sporting machines as far back as the late 1920s. For an extra £5 customers could have their engines specially tuned at the factory and to identify such engines the despatch department stencilled a star on the timing case. This developed into naming their sporting models Blue Star or Empire Star as a couple of examples. In the pre-Second World War era BSA was not known as a sporting company and actively distanced itself from racing, having experienced a disaster in the 1921 TT. The company’s chosen sporting forte became trials where reliability was important and in this sport it was incredibly successful. However, the company mellowed a little towards racing and in 1937 prepared a sporting Empire Star for semi-retired racer Wal Handley to enter at the Surrey race circuit of Brooklands. The British Racing Motor Cycle Club, which hosted events at the circuit, would award a gold star badge to any competitor who lapped the circuit at 100mph or more during a race. Wal Handley and the Empire Star won the three-lap race at an average of 102.27mph and did the fastest lap of 107.57mph. This feat earned him his gold star badge and when BSA introduced a replica of his motorcycle what else could it be called but Gold Star.

Not all that glitters is gold

There are pitfalls to budding Gold Star ownership as the iconic machine is forever connected with the B31/B33 bread-and-butter mainstay of BSA’s single-cylinder range. Confusion begins partly because BSA supplied a competition version of the B31/B33 and fitted them with alloy barrels and cylinder heads designating them B32/B34, in which form they look similar to the Goldie. This competition version was much lighter than the roadster but lacked the final extra testing which the Gold Star received. Adding to the confusion, the basic frame for all the singles, be they sporting or not, was to the same design and of all-welded construction.

A seemingly bewildering amount of letters and numbers are ascribed to Gold Stars and they all mean different specifications of engine and gearbox. A small box-out in a feature can only give the briefest guide to what they all mean so forgive the generalisation and we point you to A Golland’s book Goldie and Bruce Main Smith’s book The Gold Star for more detailed information. BSA reintroduced the Gold Star into its range in 1949 and it will have the legend ‘GS’ in the engine identification number but not the frame one. Beginning with the ZB the company altered the lettering as significant design changes arose and went to BB, then CB, DB and ended with DBD. By nature this is a very simplistic overview and doesn’t take into account frame numbering which had ZB and BB at first then stuck at CB. Gearboxes too have their own codes stamped on them and RR, SC, STD and TRI suggested gearboxes for racing, scrambles, road and trials use. When the company replaced the layshaft bushes with needle roller bearings ‘T’ was introduced into the number.