To celebrate scrambling’s centenary last year we had a rake through the archives and came up with a few things.

It seems scrambling has been a part of motorcycle sport for ever but in reality the term came quite late to the competition scene. The idea of pitting motorcycles and their riders against one another and/or the countryside was already nearly a quarter of a century old by the time members of Camberley and District MC announced their intention to hold an event to rival Yorkshire’s Scott Trial in 1924. Prior to the centenary event, which would be held on March 29, 2024, there had been much serious and light-hearted discussion in the pages of The MotorCycle over who was better at riding on rough country – northern motorcyclists or southern motorcyclists.

Naturally the CDB editor, having been born north of Darlington, knows the answer to this often-pondered question but a century ago Camberley and District MC felt a contest to determine the actual answer, while allowing it may take several runnings of such an event to do so, would be a good idea. The club’s intention to name the event Southern Scott Trial was dealt a blow when the ACU ruled it wasn’t a trial as observation played no part in the proceedings. This uncertainty over what the event actually was continued into the press in the week following its running and it was described as a trial, a rodeo and a steeplechase all on the same page in the same report! Now, the idea of a pure race across rough terrain with the winner being the first one to the finish wasn’t new; several clubs had organised such events before Camberley did but called them ‘rough rambles’ to distinguish them from trials. So, it is the honour of Camberley and District MC to go down in history as the organisers of the very first event to be termed ‘scramble’.

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

The legend was born on p410 in The MotorCycle’s edition of March 20, 1924 in a short introductory piece titled Camberley Scramble and laced with 1920s motorcycling humour such as extracts from The Motorcyclist’s Dictionary revised by the Rev Nullan Void – probably a direct dig at The MotorCycle’s correspondent Rev Basil Hart Davies, aka Ixion, who was a serving clergyman. In this piece were subtle references to the club’s physical training regime where competing in the scramble would exercise every muscle in the rider’s body. In those far-off days there were no real specialist scrambles machines; perhaps a manufacturer may have made available a Colonial Model to the sporting rider who fancied competing in off-road sport but in the main the entrant would be riding what they had. Nor were riders clad in fancy clothing such as is seen today as many favoured either the long competition coat or just sports jackets and plus-fours. Helmets were rare though and The MotorCycle felt it noteworthy to say several riders finished with very muddy shoes… imagine!

As the 1920s are a little further back in history than CDB generally goes, suffice to say the idea caught on and it wasn’t long before many more clubs hosted such events. Eventually manufacturers caught on too and began tailoring certain of their models to cater for the new sport. To sidetrack slightly here, the competition world was quite fluid with few factory riders restricting themselves to one discipline but rather riding whatever the manufacturer needed publicity for in whatever event was appropriate. The key here is ‘publicity’ and it is for this reason alone manufacturers bother with sport and the expectation is successes in competition will reflect on the bread and butter models which keep companies afloat. An oft trotted out phrase is ‘win on Sunday, sell on Monday’ which is all well and good if the machines being sold reflect what is winning. In this many manufacturers played fair and their competition machines were similar to the roadsters they were selling; yes, they might have had a larger front wheel, maybe the fuel and oil tanks were smaller, mudguards more sporting blade than touring wraparound – but put both machines together and the similarity was there. Additionally, most manufacturers listed the competition parts in their spares catalogues so owners could convert their own machines to a point.

This situation continued right up until the Second World War and immediately after it too. Yes, there had been some improvements to design, telescopic forks were ‘in’ and girder forks were ‘out’ as an example, but in the scramble for export sales it seemed the competition market would lose out. Factories could and did sell anything they could produce and making competition machines took time away from mainstream production as well as using up valuable and scarce resources – don’t forget in this period the UK Ministry of Supply would have to approve raw material purchases. Almost grudgingly a competition model would be included in the range and this machine would likely be expected to serve in any competition an owner was likely to enter and be daily transport too. Gradually though, the sporting scene defined the motorcycle and it was increasingly clear a machine needed for one sport wouldn’t necessarily work in another discipline and specialisation was around the corner.

Before specialisation though, it was the turn of the home-constructor which was probably more through necessity than desire as new bikes were few and far between. Those dealers who could get bikes were often told they had to go to riders who would put them in the top end of the results rather than those who would make the numbers up. Still, it was a decent time for events; local motor clubs would host all sorts of events, and scrambles could charge admission too. Behind this explosion of club sport there were the national and international events too, eager to put the ‘contest’ of the Second World War behind them, enthusiasts on mainland Europe organised a different, much friendlier contest involving motorcycles and called it the Moto-Cross des Nations. This team event still exists, is still hotly contested and still has the glamour of international kudos.

For some reason, certainly here in the UK, the scrambling/MX scene was never as well developed as, say, the feet-up brigade enjoyed. In fact, where there were a considerable number of trade-supported trials – a de facto British championship – for a good few years there were only a few trade-supported scrambles. In 1946 the Cotswold Cup and Lancs Grand National carried the flag for what would become the British Scrambles championship; they were joined by two or three more in 1947 but it took until 1951 for there to be an actual British championship. Just a year later, there was a European championship too.

This era saw the rise of what must be the most successful British scrambles machine… BSA’s Gold Star. In common with many of its riders the Goldie excelled in a variety of events and it may seem it ruled the roost for decades but its star shone brightly for a brief period. In the hands of home and foreign riders the Goldie dominated the scrambles and MX scene once the all-welded frame devised by their star man Bill Nicholson was adopted for the 1953 season, yet by 1959 the smaller, lighter machines were beginning to eclipse not only the Goldie but the rest of the big bikes.

Things still looked rosy for the British industry as 1960 opened a new decade, but appearances were deceptive; there were threats to UK dominance firstly from Sweden, then Czechoslovakia and Spain before finally the Japanese industry noticed this off-road lark. The results show BSA at or near the top of the home and world championships from the start of the decade but this was more to do with the calibre of rider the company could enter as the Goldie was increasingly outclassed in the 500cc contest. Something had to be done and what BSA did was rework its 343cc roadster into the ultimate machine and with Jeff Smith’s talented hands on the bars, Brian Martin’s development brilliance and the factory behind them, along came two world championships. Sadly for the UK industry, it was all amid the collapse of the once-proud motorcycle manufacturing base. BSA survived a bit longer but eventually they too were gone, possibly hastened by such things as the titanium frame escapade which cost the company a lot of money.

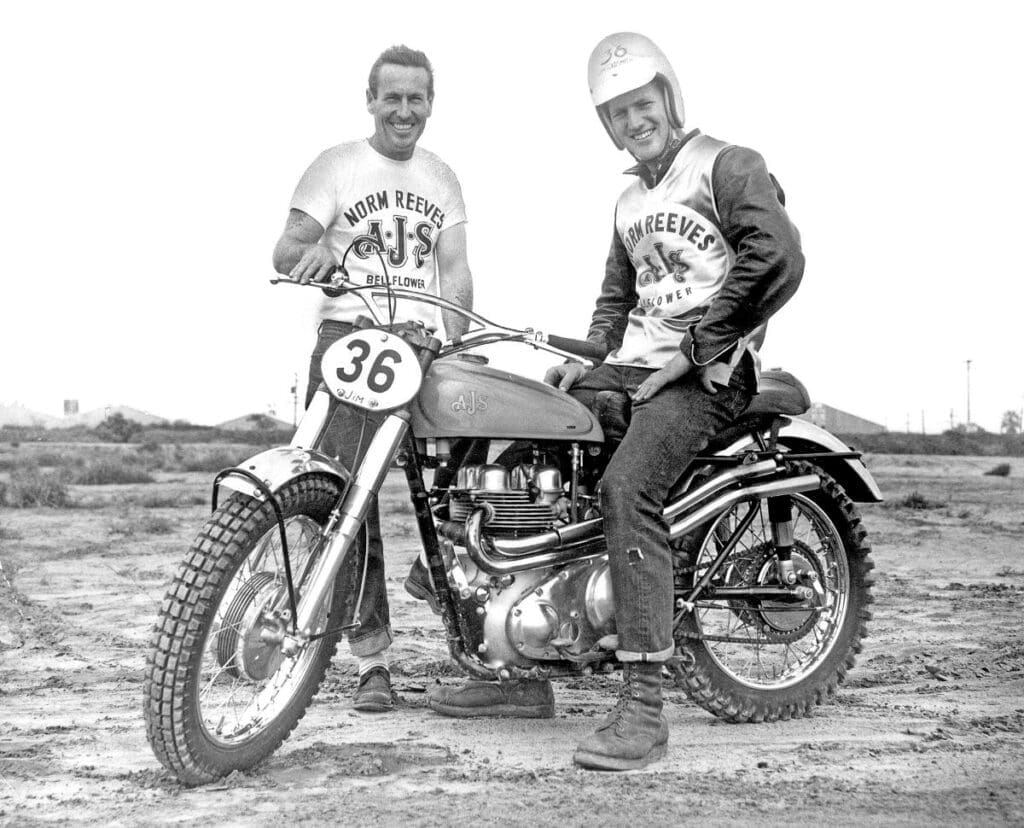

The industry was contracting rapidly elsewhere too as some crumbs of the once-proud factories were desperately trying to save themselves with innovation rather than badly needed investment. In this period came the Matchless G85, a massive 500cc traditional single which, had it been around 10 years earlier, would have made a much bigger mark. Elsewhere AJS made a brave stand with their Stormer models and indeed still exist today thanks to Fluff Brown’s endeavours. As the Seventies opened, the Japanese had a firm handle on the motocross scene; buoyed up by large volumes of small-machine sales in Asia, modern factories with state-of-the-art facilities which produced good looking, reliable and successful machines, they were the way forward.

MX or scrambling?

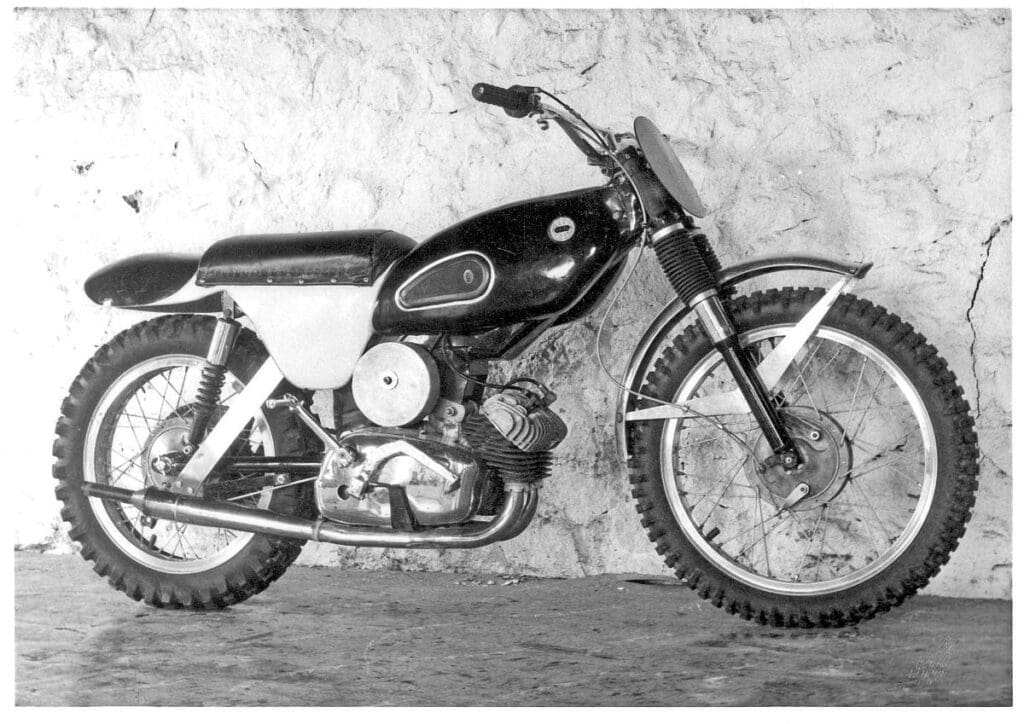

Everyone knows it was always scrambling until modern times when the term motocross, soon shortened to MX, started being used to describe a race on a closed off-road circuit with turns and jumps and mud and… well… stuff. Problem is with things ‘everyone knows’ they’re often short of the mark. It is true the UK scene did favour the term ‘scrambling’ much longer than motocross but AJS, for instance, catalogued a motocross model in its off-road range in 1956. This model is depicted in our pic of the catalogue with this boxout and a fine looking motorcycle it is too. Remember too, the MX des Nations contest started in 1947, in Holland but you knew this already… MX or Moto-Cross des Nations sounds much better than Scrambling des Nations ever could.

Not so much a scrambles timeline…

…but a reminder of some notable MX years, so it was in…1924 when the first actual scramble was held… by 1934 the Cotswold Cup was held…while in Northern Ireland Bill Nicholson first rode a motorcycle in 1939…Nicholson would join the BSA factory post-Second World War to guide the company’s Goldie to success… a special event for international teams first run in 1947, the MXdN still goes today… in 1951 officialdom caved in and announced there would be a British Championship for scrambles…in the same year a small Essex company called Invacar used scrambling to test theories for its invalid carriages, Greeves was on its way… by 1952 there was a European MX championship…British riders would win the last two European crowns before the 500cc class became a world championship in 1957…first official world MX champion was Swede Bill Nilsson on a reworked AJS 7R road racer…250cc racers forced the FiM’s hand and were grudgingly granted a European championship…by 1959 it was clear the BSA Gold Star was on the wane as Don and Derek Rickman unveiled their Metisse models…aware the Goldie was on its limit Brian Martin popped scrambles tyres on a B40 roadster and headed for the 1961 Red Marley Hill Climb… quarter-litre scrambling became world class in 1962… in 1963 Great Britain began a five-year reign at the MXdN… 1964 would see the culmination of Smith, Martin and BSA’s efforts as the world 500cc MX championship went to Birmingham… 1965, they did it again… to celebrate, BSA launched the Victor MXer… 1966, Paul Friedrichs and CZ wrested the title from Smith and BSA…for 1966 BSA cancelled the budget limit and heaped money into winning a third MX crown by building a titanium bike…1967 saw British bikes increasingly left behind as the foreign, overbored two-strokes made inroads into the 500cc class…the 250cc class had long been the property of Husqvarna and CZ…1970 saw the world change as Joel Robert retained his 250cc world crown though mounted on a Suzuki rather than a CZ…Suzuki would hold both 500cc and 250cc world titles in 1971 with Roger De Coster and Joel Robert…and same again in 1972… and 1973…1974 delivered the world 500cc title to Husqvarna’s Heikki Mikkola… De Coster declared ‘over the hill’… er no, 1975 and 1976 world 500cc MX champion was Roger De Coster… 1975 would see a Belgian trio of De Coster, Harry Everts and Gaston Rahier be 500cc, 250cc and 125cc world champions…Everts was the ‘Puch’ filling in a ‘Suzuki’ sandwich… in 1979 Honda-mounted Graham Noyce would be crowned 500cc world champion…fellow Brit Neil Hudson was 1981 250cc world champion… for 1982 the 500cc crown went to USA’s Brad Lackey…in 1985 UK’s Dave Thorpe won the first of his three 500cc world titles but here ends our CDB rundown as the archive fizzles out around the mid-Eighties. Yes, we’ve para-phrased 60 years into less than 500 words, which means there’s a lot missed… sorry… tell you what, we’ll go from 1985 for the bicentenary…

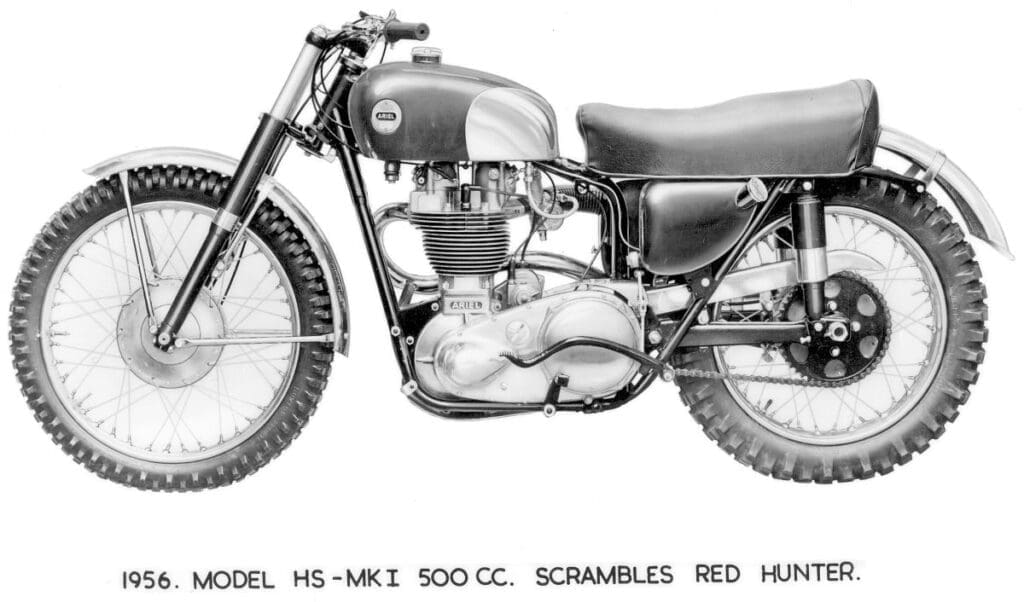

BSA Gold Star

When the subject of big singles in scrambling is raised the first machine to come to mind is BSA’s Gold Star. It could be classed as the most successful of all the big bikes and if you wanted to win in Fifties scrambles then to ride a BSA Gold Star would take you a long way towards the chequered flag. This super-sporting motorcycle is forever tied to the B31/33 roadster range though its true genesis is the Thirties M24 and the ultimate expression of it is the 1959 version. The Goldie had an all-alloy engine to the same dimensions as the B range in either 350cc or 500cc form as a range of parts was available to create whatever condition of engine was needed. This power could be matched to gear ratios so the engine was always working at its optimum performance.

So entrenched in the sporting world was the Gold Star it was possible to obtain the full range of accessories for the model which would convert it from touring condition to trials, then scrambles and also road race. In practice it is unlikely anyone actually did but it was theoretically possible.

Matchless G80CS

Matchless, or AMC really, had an interesting start to its competition range. Many private owners bought the teleforked dispatch riders’ machines from surplus sales and converted them for competition use. Of modern appearance but still with a rigid frame, they were also a 350cc. When the company introduced the 500cc G80 the same thing happened; private owners converted them to scrambles form. Things improved when the factory introduced a scrambles machine though still with an iron engine. For 1950 along came two developments in the competition range: first was an all-alloy engine then swinging arm rear suspension though, bizarrely, both innovations were not on the same machine so a competitor could buy a G80C with an alloy engine and a shorter wheelbase competition frame or the G80S, which had swinging arm suspension. The two joined forces in 1953 and the G80CS joined the range. As the Fifties progressed Matchless’ comp model gained a shorter stroke, higher performance engine and some serious performance increases. Next development was for an improved frame so riders of Dave Curtis’ calibre could and did win British championships so mounted. In recognition of the higher speeds on North American tracks, AMC introduced a performance kit which hopped the power up to more than 40bhp.

Matchless G85CS

The last gasp of the big bike in mainstream scrambling came when Matchless introduced its G85CS for 1965. Hailed as the first new AMC machine since 1960, it had an impressive specification, the most notable being the new machine had been made 98lb lighter than its predecessor which put it within 20lb of the BSA Victor. To do this AMC had created the frame from Reynolds 531 tube and added such things as a rear brake from the 7R racer which made the complete wheel 16lb less than the G80CS one while carving off ounces and grams here, there and everywhere. Using the 86mm x 85.5mm bore and stroke engine with its all-alloy construction and utilising bottom end improvements, AMC had worked on the new motor produced an impressive 41bhp. Experiments with gearing showed the new machine would be capable of 115mph had optimum ratios been fitted. Helping in this power were two race-proven accessories – Amal’s GP2 carburettor and Lucas’ racing magneto. Sadly for the model, it was very much a big rider’s machine and the lighter, easier-to-ride two-strokes from Eastern Europe outclassed it but it remains a fabulous final gasp of the big bike.

A Victor’s spoils

When Jeff Smith won his second world championship in 1965, BSA was on the cusp of introducing the machine which would celebrate this feat. Patiently developed from the company’s B40 roadster, Smith’s 1964 championship machine was of 420cc and the culmination of many hours of work. BSA seemed to view it as a rolling testbed for ideas with the happy result of having a championship win as a side benefit rather than a precursor to a production machine. This seemed to change for the 1965 season and perhaps the decision to produce a replica and name it the Victor GP was an inspired decision. By the time it got to production, capacity had grown to 441cc with a bore x stroke of 79mm x 90mm. At 255lb it was a little heavier than the factory machine but still a light machine and with 34bhp to propel it forward this was reckoned to be the closest thing to an actual works machine as a private owner could get. Everything about the machine spoke of quality: from the chrome molybdenum fork stanchions to the oil-bearing frame made from thin gauge Reynolds 531 tubing, there had been no skimping on materials. Smith himself was to ride one of the six pre-production standard machines rather than his factory special at the final round of the 1965 world championship and he finished third on it, a fitting testament to the 441 Victor GP.