AMC twins may be oft overlooked but are another wonderful way into British twin ownership

Words and photos by Matt

Alright, so you want a British classic bike, an excellent choice of steed. Perhaps you’re not too bothered with getting a particular make or model, or era. But have you considered the difference between having one, two or three cylinders? Have you thought about suspension, comfort, parts reliability and useability?

For some, all these questions have been answered and the goal is defined. For others, the choice could be endless. And sometimes – in fact, a lot of the time – the choice has no particular reason. It could be as simple as ‘that one turned up’, just as much as ‘it must be that one because my uncle had one’. It’s a wonderful problem to have.

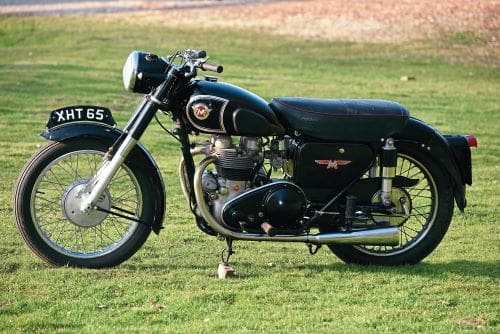

Triumph, BSA and Norton have earned their standings in our worlds as well as those away from the old bike world. If you’re seen on a T-shirt, you’ve made it. But AMC? Matchless? AJS? It’s time they had some light on them, and this month we look at one of their best – the 600cc, twin-cylinder Matchless G11 and AJS Model 30.

Twins – oh, don’t they grow up quickly

Triumph broke the tape to be the first British company to bring out a parallel twin-cylinder; the Speed Twin, in 1937. But due to the war effort and factory being bombed it would be 1946 until people had a chance to see the new bike. It gave the British rider who was used to singles of various sizes a luxury to choose, with power, torque, smoothness and speed with its light cycle parts. It would take BSA, Norton, Royal Enfield and Ariel some time to catch Triumph up with quality variations of the same engine design: an air-cooled, parallel twin around 500cc, with overhead valves operated by pushrods and separate gearboxes.

Matchless and AJS (by now their models were largely the same as each other and other than minor differences were simple badge engineering) were last to the party. This is strange considering they had experience of V-twins and the competitions departments were open-minded to say the least, with the supercharged V4 and later the Porcupine engine on their CVs, but their singles had been selling well. And to make matters worse for their loyal fans, they may have seen the new twin at the motorcycle show that year, the Matchless G9 or the AJS Model 20 500s, but it was designed for export only – British customers would have to wait.

Those customers patient enough not to buy something else found a machine that was different to the crowd, both inside and out. The engine was designed by Phil Walker and had the usual parallel twin with a 180-degree crank, but the crank was supported by three huge bearings, one at each end as per all others, and one in the middle. This, unlike the firing order or a balancing shaft, was there to help minimise vibrations and increase life expectancy – they wanted a tough engine. And it looked good, too, with lovely shiny aluminium cylinder heads and rocker covers sitting above iron barrels that were separate from each other like Enfields. The middle crank bearing helped oil feed, as did the twin pumps; the one-piece crank would have had advantages and disadvantages in manufacture but was standard fayre for the car industry. The twin cams were gear-driven along with the auto-advance magneto behind the barrel, while in front the Lucas dynamo supplied lights so, everything looked good. An industry-standard Amal carb fed the engine through an alloy manifold.

The engine fed the power through the primary drive and its pressed steel cover (with alloy sprung sealing belt) to a gearbox made by Burman and later AMC’s own gearbox, often to be found in many bikes, including Norton. Both types were one up, three down.

One element that did stick out was the new swingarm frame, with twin ‘Jampot’ dampers (which can be rebuilt). The AJS stuck with a saddle and perch for any pillion, but the Matchless had a new-fangled twin seat, and with the Teledraulic forks up front, the AMC offerings would be among the most comfortable motorbikes around.

In fact, and this is a personal opinion of the writer, but the Matchless is one of the best-designed and best-looking bikes of the era. The new frame and swingarm did away with any afterthought look of a plunger set-up, the frame sidebars are neatly filled in with a tool box on one side and an oil tank the other, with the central area feeding the carb still air, the neat headlamp adorning the top of the hydraulic forks, and the smoothed look of the functional mudguards look as if it has all been designed together – not shoved together from whatever is in the parts department. Even the megaphone silencers look smart and nothing like any other road bike – and sound great. The AJS had a larger, four gallon fuel tank and a more traditional silencer.

Matchless and AJS had racing pedigree, which must have helped sales, but they did have problems. The engines had a smooth delivery of power in any gear, making them great all-day riders. And the comfort made that all the more possible. However, they were quickly known for having oil leaks sprouting up over the engine, while the brakes were not great and the rivals nearly all had larger diameter drums. The handling was great once riders got used to it, but the frame was not the stiffest and riders were not used to decent forks and swingarm rear ends, leading to some feeling a ‘loose’ sensation. But the largest issue was the ‘ultra strong’ bottom end. While the three bearing bottom end was a good idea in theory, many found the lack of flex the crankshaft had was leading to extra-high vibrations being carried through the frame to the rider. At worst, there were cranks snapping, but this is most likely to have been from thrashing with low oil level, old oil, or low pressure.

A bit of background – who is AMC?

There were many, many British manufacturers of motorcycles in the early part of the 20th century but over time, many went to the wall or were incorporated from several.

Briefly, Matchless, a London company from Plumstead, started in 1899. Run by Henry Collier and his two sons, the firm won several TTs to help bring its name into the public eye, which helped as its rivals were awarded contracts for bikes in the First World War.

Nethertheless, it built its own engines, became well-known for its V-twins and later in the ‘30s would supply both Morgan cars and Brough Superior.

Meanwhile, AJS, from Wolverhampton, was founded by the Stevens family around the same time as Matchless. Again it built its own engines and again built an impressive model range. It, too, didn’t make motorcycles for the British war effort but was contracted by Russia for a brief time. It also used racing for marketing, though seemed to be more successful later, whereas Matchless had used its winning earlier. AJS was resourceful, over the years building buses, cars, and even radios, but with some bad luck, unfortunate timing and allegedly bad accounting advice, it was declared bankrupt in 1931 (after clearing debts, we may add). Matchless bought the company, although BSA had also tried.

So, as of 1931, Matchless owned AJS, and in 1937 bought Sunbeam Motorcycles, also of Wolverhampton, from industrial giant ICI. And so AMC (Associated Motorcycles) was formed, making a huge concern with massive power in the industry.

Sunbeam would be sold in 1944 to BSA, Francis-Barnett and James would join the family, and in 1953 Norton would join. The party came to an end in 1966, but that’s all for another day.

The G11/ AJS Model 30

By 1956 the G9/ Model 20 had been on production for eight years and had many small changes. Better forks, better brakes, different mudguards, a quick release rear wheel, a primary case that leaked less, an air filter, and reduced gearing by changing the engine sprocket down a tooth from 21 for more spritely acceleration. For ’56, the range saw a new frame with a longer seat, nicer oil tank and tool box. And the largest market, bearing in mind the Government’s mantra of ‘export or die’, was the USA, which was continuously asking for bigger engine displacement to keep up with home market bikes. Earlier in 1954, the USA had received the G9B, which had been bored out to 550cc, but then in ’56 it went to 593cc with a compression ratio of 7.5:1, and the G9 continuing as a 500 but with a boosted compression of 7.8:1. The 600 was the G11/ Model 30 and had different cams, and in that year the twins moved to the AMC gearbox – a ‘box that has few haters.

Something special for the weekend, sir? The CS and CSR models

With desert racing and scrambling being so popular in the USA, AMC created the CS in 1958. They had a high-compression engine in the off-road singles frame, with alloy mudguards and a two-into-one exhaust system. The lights were easy to remove, tyres were wider, the petrol tank was a tiny two-gallon one, and it wore high ‘bars. The CSR, created in the same year, was the Rocket Gold Star. It benefitted from all the CS goodies but retained road tyres, standard handlebars and road tank.

For kudos, Vic Willoughby, racer and road tester for The Motor Cycle, rode a G11CS at the MIRA speed oval at 100mph for an hour. The bike was standard barring one tooth more on the gearbox sprocket, and it did the feat admirably. Afterwards, it was ridden back to London and stripped to be inspected, with little trouble found. A good publicity stunt.

In 1959 the American yell for more cubes came again and the engine taken out to 646cc; a new crank with longer stroke and larger barrels were needed. The G11/ Model 30 was no more and the G12/ Model 31 was the new kid on the block.

Riding the G11

So often in motorcycling, you hear how the largest isn’t necessarily the best when it comes to engines. That’s down to original designs being taken out too far, ruining the balance. I don’t know about the G12, but riding along on John Johnson’s G11 600cc is like riding a G9 500cc but with a little more forward motion with every move of the throttle. John’s bike hadn’t been used for some years and though inside, we had to wash it before we took photographs thanks to the bird droppings and everyday dust that accumulates in a workshop. But with Neville at the helm, a flooding of the carb and some vigorous kicks finally got the Plumstead machine running; first roughly, but once the plugs cleaned themselves up, cleanly and spritely.

The riding position is odd as you get on; it’s part old bike, part modern bike. The nacelle and fixed footpegs contrast with the comfy, modern twin seat and standard, modern-shaped handlebars. Clicking up to first with your right foot wakes you up and letting out the heavy clutch confirms that you are indeed on an old bike.

John’s bike is louder than many as the baffles are out of the original megaphone silencers, but it’s not too loud. And it does feel like it’s getting hot after a while, though we were stopping and starting for photos. It might have you changing up slightly lower down the rev range, but there’s torque to pull you forward from practically any gear anyway. In fact, you really don’t have to worry what gear you’re in, as once in top, you tend to stay there. I found myself cruising around 55mph – a 600cc twin should easily cruise at more than that, but the gearing feels short – it may have been this example, but if unsure, speak to the excellent club.

The handling and the way the G11 handles the bumps is great. Old dampers are not as good as modern shocks and Teledraulics are not as good as even basic modern forks. But they are miles better than plunger rear ends and old-style forks and the seat is comfier than a saddle, feeling more modern as well.

But don’t let this Jeckle and Hyde personality catch you out. The engine is strong, the comfort high, but the suspension doesn’t give much away in the handling stakes – you’re on a 66-year-old bike with 66-year-old geometry and 19in wheels with old tyres. And the brakes are more like assistance to the engine braking. Plan ahead.

Once in the right mind, once you’ve reminded yourself you’re on a classic, you can relax. The Matchless is more BSA than Triumph, with a sturdy feel, but it feels lighter than a Beeza, and the gearbox is lovely. After an admittedly short ride, I feel I could do some real miles on a G11.

Do you want a Matchless G11/ AJS Model 30?

They’re smart and well-designed, mainly easy to work on, the owners club and spares department are excellent, they were made in enough numbers for plenty of parts in auto jumbles and lots of books for reference, and they have a wonderful racing pedigree.

They are a classic that is comfortable all day, even two-up, are generally reliable and are a genuine classic with modern-day niceties. The ride it gives is as good as any 1950s/1960s twin, with a rorty engine and planted handling, and you’ll be riding something just that little bit different. If it’s of interest, they can be had for a fraction you’d pay for a Triumph. To get a G9, G11 or G12, expect to pay between £3500 and £5000 for a runner. I’d say that makes a lot of sense for a bike that will make you smile every ride.