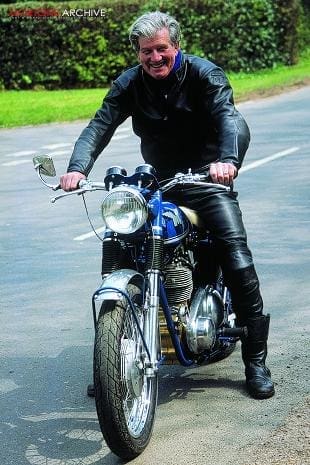

John Horn lives in a delightful country cottage. He was the creator of its lovely garden, he’s a member of the parish council, and he’s on the village hall committee. He’s the organiser of the village fete, and he mows the lawns around the church. But, when not acting like a pillar of society, he goes blasting round the place on a Matchless single you can hear in the next county. John was born just down the road; everybody knows him; and nobody has nailed an ASBO to his garage door. Instead, his neighbours ‘take the mickey’ when they get the chance!

The noisy Matchless isn’t just a humdrum cooking single – no disrespect intended – but a replica of an exotic beast; the ‘Golden Eagle’ G50CSR; a G50 road-race engine in the rolling chassis of a CS scrambler, but with silencer, lights and a horn. In 1962 AMC built 25 of these devices and all went to the States in a partially successful ‘con’ intended to persuade the AMA – the governors of US motorcycle sport – that the G50 engine was a kosher part of a production roadster and was therefore eligible for national championship events.

John has owned a lot of bikes; a Series C Rapide, a Gold Star, a Bonneville, and assorted racers, just to list a few. But he was unaware of ‘Golden Eagles’ until October 2003 when saw one pictured in a book and decided, there and then, that he simply had to have one. Buying it wouldn’t be an option. There are only half a dozen left; if that worldwide. Most of them were disembowelled on arrival in the States and the engines used for racing; so it had to be a replica. For most of us an engine would present to the biggest snag – you can’t pick them up at autojumbles, and they don’t come cheap – but John had got one in his shed; as part of a G50 that he’d bought in 1987! Three years prior to that – when he was only 50 – he had started racing, firstly on a 7R ‘Nay’: then a 500cc ‘Manx’, then on to the G50. John says, modestly, that he was never very good at it!

a Series C Rapide, a Gold Star, a Bonneville, and assorted racers, just to list a few. But he was unaware of ‘Golden Eagles’ until October 2003 when saw one pictured in a book and decided, there and then, that he simply had to have one. Buying it wouldn’t be an option. There are only half a dozen left; if that worldwide. Most of them were disembowelled on arrival in the States and the engines used for racing; so it had to be a replica. For most of us an engine would present to the biggest snag – you can’t pick them up at autojumbles, and they don’t come cheap – but John had got one in his shed; as part of a G50 that he’d bought in 1987! Three years prior to that – when he was only 50 – he had started racing, firstly on a 7R ‘Nay’: then a 500cc ‘Manx’, then on to the G50. John says, modestly, that he was never very good at it!

“But I did enjoy myself, although the best I ever managed was a fourth at Silverstone. Even then I thought that they’d miscounted on the laps! I nearly always made bad starts – I found it hard to start a racing bike – and when I tried to catch the field I’d get faster and faster until I’d end upon my ear! On one occasion when Bob Newby lapped me I tucked in behind him, but soon found I was on the grass, at 100mph! My last race was at Mallory. I’d had the usual rotten start, tried to overtake a bunch of riders on the outside of The Esses, and woke up underneath a pile of tyres. To my surprise I wasn’t hurt, but decided there were other things in life, like my wife and family, and a successful business, and it was best to be alive in order to enjoy them! So after that I gave up racing, but I kept the bike.”

“To my surprise I wasn’t hurt, but decided there were other things in life, like my wife and family, and a successful business, and it was best

to be alive in order to enjoy them! So after that I gave up racing,

but I kept the bike.”

Although he had a donor for the engine John was doubtful that he had the engineering skills to go ahead – “I’m a better gardener than an engineer” – so he asked his mate John Burton if he’d help him build a ‘Golden Eagle’. He didn’t have to twist his arm! JB – a retired consultant engineer, Ariel Square 4 expert and enthusiast, and Canal Zone speedway champion two years running when he served in Egypt with the REME – couldn’t wait to get ‘stuck in’. The understanding was that he’d do all the clever stuff, while John would buy a CSR in good condition, act as banker, and also do the ‘gophering’.

It wasn’t long before JB received ‘a great big heap of bits’. He reduced John’s engine down to its component parts; inspected every item, found that it was all in decent order, and meticulously put it back together. It’s a simple enough unit, but low-tech as it is you need to be a good mechanic to assemble one correctly – I briefly owned a 7R, in bits, and I wasn’t short of encouraging advice from kindly friends on how to go about the reconstruction. ‘For God’s sake don’t you touch the engine. You’ll be sure to **** it up’ was a typical example!

received ‘a great big heap of bits’. He reduced John’s engine down to its component parts; inspected every item, found that it was all in decent order, and meticulously put it back together. It’s a simple enough unit, but low-tech as it is you need to be a good mechanic to assemble one correctly – I briefly owned a 7R, in bits, and I wasn’t short of encouraging advice from kindly friends on how to go about the reconstruction. ‘For God’s sake don’t you touch the engine. You’ll be sure to **** it up’ was a typical example!

At 10.5:1 the compression isn’t fierce, but to make it easier to start JB lowered that to roughly 9:1; not with ‘plates’ between the barrel and the crankcase as that method would affect the fitting of the wonderfully distinctive, ultra-light, magnesium alloy, timing case. Instead he carefully machined the top edge of the piston, thus effectively enlarging the combustion chamber. Another aid to starting was to swap the GP carburettor for a brand-new 1000 Series Amer. That set me back £300,’’ John says.

The next thing was to fit the engine, and this meant modifying the frame by cutting ½in off the nearside engine mounting lugs, and making spacers for the other side to move the engine sprocket into line with the sprocket on the gearbox from the CSR. The racer’s five-speed gearbox was considered, but rejected, largely as there wasn’t room. And anyway it didn’t have a kick-start mechanism, and wouldn’t have conformed to ‘Golden Eagle’ spec.

Even so, JB had to make new engine/gearbox mounting plates, and cut away the centre of the topmost gearbox mounting lug to clear the bottom of the Lucas racing-type magneto. That came off the donor racer – It would have cost a ‘grand’ if I’d had to buy one – but it didn’t have a mechanism for retarding sparks, so in order that the bike would start JB had to make one.

There were further complications when it came to the electrics. The originals had a separate 6v dynamo cradled in the forward engine plates and driven by a belt from the drive side crankshaft. The primary chain case, which was extended forwards and upwards to include the belt, was a throwback to the pressed tin type that the factory ‘binned’ in 1958. It was very nicely fabricated, but both clumsy and unsightly.

There were further complications when it came to the electrics. The originals had a separate 6v dynamo cradled in the forward engine plates and driven by a belt from the drive side crankshaft. The primary chain case, which was extended forwards and upwards to include the belt, was a throwback to the pressed tin type that the factory ‘binned’ in 1958. It was very nicely fabricated, but both clumsy and unsightly.

They decided they’d do better, forget about a dynamo and instead would use the alternator from the CSR, a decision that involved JB making a flanged stub-shaft on which to mount the alternator. This shaft has an internal thread in the flanged end and screws onto the crankshaft where it doubles as a nut to hold the engine sprocket on its splines. An elegant solution, particularly as it meant that they could use the polished alloy chaincase from the CSR, but, of course, there was a drawback! The engine breathed out through the drive side crankshaft and the solid stub-shaft blocked the hole! JB wasn’t keen to drill into the crankcase so he devised new breathing apparatus which was fitted to the cam-drive cover.

The Golden Eagle battery carrier, which was tucked beneath the seat on the offside of the bike, looked like something of a ‘lash-up’, or an afterthought at best, although in fairness it was meant to be a sort of competition motorcycle. John had a long, slim oil tank from the offside of the CSR and that was cut about to take the battery. Hardly prototypical but much, much neater. What he still lacked was a long, slim oil tank for the nearside of the replica. Nearside oil tanks were unique to competition models made by AMC as they left room on the offside of the bike to fit a tubular air filter to the carburettor. They are also very hard to find – as rare as dragon’s droppings, politely known as fewmets – and John had almost given up when he came across a mangled one, at an enormous price, and had it beaten into shape. A CS model petrol tank was easier to get, but just as costly.

They didn’t bother looking for an original exhaust pipe. 2in in diameter they were a sort of outside drain, and totally exclusive to the limited edition. John had one made – for £120 – but it was a dreadful thing and absolutely useless; dented to avoid obstructions instead of going round them. In the end they took the bike to Tubecraft, Woking, who kindly made the bends. JB then made a complicated jig, from wire, which held the straight bits in between the bends, ‘tacked’ each joint, took the whole thing off and welded it together! The silencer is Gold Star, but it doesn’t twitter.

They didn’t bother looking for an original exhaust pipe. 2in in diameter they were a sort of outside drain, and totally exclusive to the limited edition. John had one made – for £120 – but it was a dreadful thing and absolutely useless; dented to avoid obstructions instead of going round them. In the end they took the bike to Tubecraft, Woking, who kindly made the bends. JB then made a complicated jig, from wire, which held the straight bits in between the bends, ‘tacked’ each joint, took the whole thing off and welded it together! The silencer is Gold Star, but it doesn’t twitter.

The magnesium timing cover and the crankcase have been painted gold, not merely to conform to 7R/G50/’Golden Eagle’ image, but largely to protect them from the atmosphere which would cause the surfaces to crumble to a whitish powder. Matt black or bathroom green would probably provide the same protection, but wouldn’t look as nice against the replica’s Alfa Romeo Francia blue finish, which is as close as you can get to the paint the factory used.

Not only does the John’s ‘Golden Eagle’ look the business; it is just as nice to ride. In fact, it’s nicer than a standard CSR because, at 80mph or more, the Matchless racing single is a great deal smoother than the sporty Matchless twin! The ‘oversquare engine – bore and stroke are 90 x 78mm – is magnificent in every way. And even in its present state of tune; semi-strangulated by the so-called silencer, and with a moderate compression ratio, it is – in terms of top speed – just as rapid as the CSR, although at 496cc it has less ‘cubes’.

Acceleration is impressive; probably much quicker than the standard CSR, though the racket that the bike kicks up can be a bit inhibiting near human habitation, or the police! In racing mode the engine would be good for 50bhp, or slightly more, but due to all the mods output must have dropped by 10 per cent, at least. Even so, mid-range torque is hefty; top-end power is wonderfully exhilarating, and the engine feels unstressed, probably because I wasn’t stressing it in any way. The robust and straightforward OHC cam, 2-valve unit – virtually a larger version of the famous 7R introduced in 1948 – has a massive dry-sump bottom end and a pair of oil pumps. It was designed to cope with thrashing round the TT Course at 7000 revs – and maybe more – for hours on end. If you tried to ‘wring its neck’ on an A-road or a motorway you would only make it laugh, and mostly likely lose your licence. In road conditions I would say that it’s unburstable!

I was less keen on th e starting. John tells that me that it starts up easily enough, but when I tried it kicked and spat and sulked. He soon lost patience with my efforts, and though he got it started it didn’t look that easy! He goes all over on the bike and I’m convinced he pays a flunkey – 18 stone of servile rockape with enormous big boots – to follow him about to start the thing! The factory didn’t bother with reducing the compression ratios of their G50CSRs, and getting one of them to start must have been a bad-tempered business!

e starting. John tells that me that it starts up easily enough, but when I tried it kicked and spat and sulked. He soon lost patience with my efforts, and though he got it started it didn’t look that easy! He goes all over on the bike and I’m convinced he pays a flunkey – 18 stone of servile rockape with enormous big boots – to follow him about to start the thing! The factory didn’t bother with reducing the compression ratios of their G50CSRs, and getting one of them to start must have been a bad-tempered business!

The gearbox is just standard AMC and has no vices. Gear changes aren’t ‘snappy’ but they’re positive and smooth. Four speeds are quite sufficient, because of all the torque ‘on tap’. Top and third are fairly close with overall ratios of 4.79 and 5.85:1. On the present 21T engine sprocket John says that he has calculated that 6000rpm in top should propel him to 100mph, or more, but I’m sure he found that out in practice on the local bypass! He thinks it would be faster on a 23T engine sprocket, but doesn’t want to have to slip the clutch in first.

The riding position is ideal for legal speeds – maybe less so at ‘the ton’ – footrest in the right place; highish seat, and the rider leaning slightly forward. Being long in leg and body, I feel a bit ‘perched up’ on a standard CSR, and the petrol tank is just a bit too broad for comfort, although it could be useful for pre-natal exercises. The special export ‘Golden Eagles’ had enormous handlebars – high, wide, unattractive, and ergonomically absurd – but John has gone for upswept touring bars, and with its narrow tank the replica feels very like a 1950s ISDT bike. It would have been a very good one, too! Equally important; the cable runs are all correctly routed and the controls are light and smooth.

The steering and the handling are fine, although the forks are fairly softly sprung and damped, and the cradle frame is nothing very special. The back end is a bolt-on subframe, and the pivot for the swinging arm is welded to the single seat tube, but this arrangement must be stiff enough as the bike feels stable and predictable; and doesn’t have a tendency to wander off a chosen line. The makers had sufficient confidence not to fit a steering damper, and I didn’t feel the need for one. Tyres are Avon Road Runners; 19 x 3.25 up front and a 19 x 4.10 on the back wheel. The 7in drum brakes are very neat, but would be barely adequate for rapid ‘two-up’ riding.

All in all, a truly lovely motorcycle – what a pity AMC didn’t make the ‘Golden Eagle’ as a genuine production model, though they would have been expensive. Due to the improvements that the two Johns made; the alternator, battery box, aluminium chaincase, and the handlebars; it is not a perfect replica. You could say it’s a ‘Golden Eagle’ once removed, and all the better for it! The only comparable machine that springs to mind is a featherbed-type Norton International. I’ve always lusted after one of those, but now I think I’d rather have John’s bike!

All in all, a truly lovely motorcycle – what a pity AMC didn’t make the ‘Golden Eagle’ as a genuine production model, though they would have been expensive. Due to the improvements that the two Johns made; the alternator, battery box, aluminium chaincase, and the handlebars; it is not a perfect replica. You could say it’s a ‘Golden Eagle’ once removed, and all the better for it! The only comparable machine that springs to mind is a featherbed-type Norton International. I’ve always lusted after one of those, but now I think I’d rather have John’s bike!

Which brings me to his ‘mickey-taking’ neighbours. While I was taking photos of him sitting on the bike a Land-Rover drew up across the road. The driver, an attractive girl, wound down her window, smiled at John, and sweetly asked, “Who’s a pretty boy, then’?” She didn’t bother waiting for an answer. She just laughed and drove away!

I wonder. If I owned a ‘Golden Eagle’ would nice young women smile at me? No. I don’t suppose they would. But then, I reckon I could live with that!