The need was pressing, the calendar relentless. Under Dennis Poore, the Wolverhampton-based Manganese Bronze Holdings company (owners of Villiers Engineering, to name but one) had acquired the wreckage of the collapsed Associated Motor Cycles empire. Now, a determined effort was to be made to salve the Norton name from the Plumstead mire and, once again, give it world-wide respect. But this was late 1966, and the target date for the reborn Norton was the Earls Court Show of November, 1967.

” So”, asked Dennis Poore, chairing the table-full of talent called to his Kensington office, “what are we going to make?” From Villiers had come designers Bernard Hooper and John Favill (who together had “gone independent” for a year, but who had returned to the Villiers fold at the special behest of Dennis Poore to work on a stepped-piston engine project). Also from Wolverhampton were road-racer Peter Inchley of the development department, and Villiers production manager, John Pedley. Plumstead contributed chief designer Charles Udall, and ex-AMC works director Charles Summerton.

One possible answer

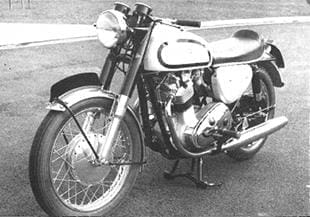

What were they to make? Good question, but there was one possible answer. Veteran of the Velocette concern (where he had worked on the M-series engines, the Roarer, and the LE, among other designs), Charles Udall had caused considerable surprise in the industry when, in 1961, he left Hall Green to join the AMC factory. At Plumstead he had occupied his time in designing a double-overhead-camshaft vertical twin (code-name, Project 10) and in the final three years of the factory’s existence the P10 had covered a considerable test mileage; much of the testing had been done at the Motor Industry Research Association track at Lindley, near Nuneaton, where I saw it myself on various occasions while carrying out Motor Cycle road tests — but of course, anyone with a MIRA pass is sworn to secrecy concerning anything he may see there, so nothing ever appeared in print. As I recall, though, it sounded infernally clattery!

The bike wore Norton colours and employed a cut-and-shut version of the famous Featherbed frame. Its engine was four-speed unit-construction and, reputedly, it had begun as a 750cc, but soon was enlarged to 800cc.

The bike wore Norton colours and employed a cut-and-shut version of the famous Featherbed frame. Its engine was four-speed unit-construction and, reputedly, it had begun as a 750cc, but soon was enlarged to 800cc.

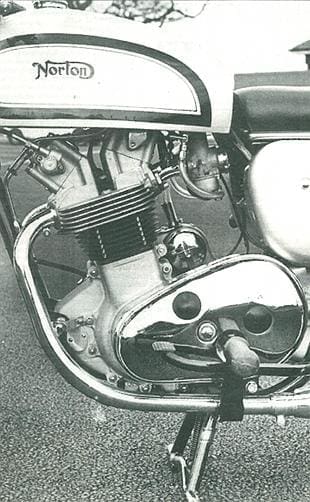

Most notable feature of the power unit was a triangular arrangement of small-diameter, chromium plated tubes at the timing side, through which was threaded a chain of inordinate length (something like four feet of it, as Bernard Hooper recalls!) to drive the twin camshafts. In fact the chain was even longer than one might guess from external indications, for it ran from a small engine-shaft sprocket, up and around the camshaft sprockets (twice the diameter of the engine-shaft sprocket, to provide the necessary twoto-one reduction) then back to the timing chest where it doubled around an adjustable jockey sprocket before rising upward and rearward to drive the magneto.

The narrow tubes through which the chain ran were lined with PTFE — the stuff that is used to coat non-stick frying pans — and each tube was located in the cambox end covers, and in the vee-shape bracket on top of the timing chest, by 0-ring oil seals. Camshaft sprockets were secured to the shaft ends by a vernier arrangement reminiscent of vintage AJS magneto-drive sprockets, to permit fine tuning of the valve timing.

Naturally, to use a split-link in the cam-drive chain would be unthinkable, and so it was necessary to assemble the whole business of tubes and castings, rivet the chain, then offer up the gubbins to the engine. Should there be an oil leak anywhere in the assembly, then hard luck! The whole affair had then to be dismantled and reassembled while the fitter kept all his fingers firmly crossed!

During the development stage, AMC discovered a number of bad vibration problems, and development engineer Wally Wyatt had tried fitting rubber bushes to the engine mountings; but because the pivoted rear fork was carried from the frame in the conventional manner, distortion of the mounting bushes when the engine was under load threw the rear chain off its sprockets.

However, it would seem that even before there was any talk of a takeover of AMC, the possibility of producing the Norton P10 at Wolverhampton had been discussed, and drawings of the engine had been despatched to the Villiers factory. With the takeover an actuality, Dennis Poore now recruited Dr. Stefan Bauer from Rolls-Royce, to lead the team charged with restoring the Norton name, and at some time a decision must have been made to adopt the P10 as the basis of the new model.

However, it would seem that even before there was any talk of a takeover of AMC, the possibility of producing the Norton P10 at Wolverhampton had been discussed, and drawings of the engine had been despatched to the Villiers factory. With the takeover an actuality, Dennis Poore now recruited Dr. Stefan Bauer from Rolls-Royce, to lead the team charged with restoring the Norton name, and at some time a decision must have been made to adopt the P10 as the basis of the new model.

“I could hardly believe it”, recalls Bernard Hooper. “Our understanding was that we had been called to the Kensington meeting to give our recommendations. What was very surprising also, at the Kensington gathering, was the attitude of Charles Udall, for he appeared very critical, very acid in his comments, and I don’t think Poore could have been very impressed.” (Presumably not, for Udall was soon to be sent on a period of ‘sick leave’).

It would seem that Udall had not forgotten his Velocette training, for the one-piece crankshaft of the P10 ran on a pair of taper-roller main bearings, in the same manner as the Vela Viper and Venom. “But what worked well with the very narrow crankcases of a Velocette single,” says Bernard Hooper, “was rather less happy with the long shaft and bulky bottom-end of the P1O, and it meant the taper bearings had to be pre-loaded by 11-thou when cold, so that there would be no end play when the engine warmed up.”

From January 1967, the design team under Stefan Bauer went ahead on redesigning the P10, in various locations. Tony Dennis, at Plumstead, made a total revision of the bottom-end. At Wolverhampton, Bernard Hooper evolved a totally new cylinder head and camshaft drive layout, while gearbox specialist John Favill re-stressed the P10 gears and modified the tooth form. Meanwhile Bob Trigg (late of Ariel and BSA) was given the task of laying-out a new frame to Stefan Bauer’s brief — which specified a backbone tube of large diameter and immense rigidity.

The project was given a new code-name, the Z26. Hooper’s new cam-drive had the chain running from a countershaft at the rear of the cylinder block and, passing between the cylinders, driving the rear camshaft; from there, a short chain drove the front camshaft. “This was not only neater, but cheaper,” Bernard points out. “The original P10 design embodied rocker arms which required fourteen different machining operations. The Z26 head used bucket tappets (actually, a Jaguar stock item). I can’t remember if the Z26 was ever put into a frame, but in any case we had been given the deadline of November 1967 for the new Norton to be announced, and by June it was becoming obvious that there was no way we would meet that target with the Z26. The production people, for example, needed nine months to get it tooled up for production.”

The project was given a new code-name, the Z26. Hooper’s new cam-drive had the chain running from a countershaft at the rear of the cylinder block and, passing between the cylinders, driving the rear camshaft; from there, a short chain drove the front camshaft. “This was not only neater, but cheaper,” Bernard points out. “The original P10 design embodied rocker arms which required fourteen different machining operations. The Z26 head used bucket tappets (actually, a Jaguar stock item). I can’t remember if the Z26 was ever put into a frame, but in any case we had been given the deadline of November 1967 for the new Norton to be announced, and by June it was becoming obvious that there was no way we would meet that target with the Z26. The production people, for example, needed nine months to get it tooled up for production.”

But there was an alternative. The Norton Atlas (a 750 cc development of the long-in-the-tooth Dominator design) had turned out 47bhp when it was last in production; in the meantime, work on the Atlas engine had been continuing on a low profile, and it was already producing more power than the P10 — even in its redesigned Z26 form— was likely to do.

Double-knocker twin

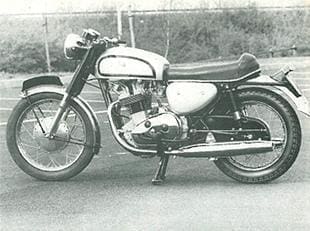

So Manganese Bronze (or rather, by this time, Norton-Villiers) decided to forget about the ungainly double-knocker twin and, instead, concentrate their efforts on what was really an Atlas MkIII. This would employ the more powerful version of the Atlas engine and, because the tooling already existed, would involve no new and expensive factory layout. The frame would be the big-backbone frame that had been devised for the Z26, and to give the new model a more thrusting and modern look the cylinders would be canted forward.

There was still the little matter of the flexibly-mounted engine causing the chain to jump its sprockets, and various attempts to find a cure included a steel cable to resist the pull under acceleration (Francis-Barnett had earlier experimented with something of this nature). Even so, some vibration would still be transmitted through the cable link to the frame.

In a flash of inspiration (it came to him while travelling by train from Euston to Wolverhampton) Bernard Hooper suggested what seemed, on the face of it, a nutty idea. How about pivoting the rear fork from the engine-gearbox mounting plates, not from the main frame? That way, the engine, gearbox and fork would be a sub-assembly insulated from the frame and rider. Recognise the recipe?

In the joint names of Bernard Hooper and Bob Trigg, a patent was applied for (similarly, on the original patent application for the backbone-type frame, the ‘first and true inventors’ are quoted as Bauer, Hooper, and Trigg). And so the new Norton was born. Not the P10; not the Z26; not even the Atlas MkIII. In the AMC collapse, the old James company had been submerged — but maybe not quite without trace, for now Norton-Villiers rescued one of the old James model names, to dub the new twin the Commando.

In the joint names of Bernard Hooper and Bob Trigg, a patent was applied for (similarly, on the original patent application for the backbone-type frame, the ‘first and true inventors’ are quoted as Bauer, Hooper, and Trigg). And so the new Norton was born. Not the P10; not the Z26; not even the Atlas MkIII. In the AMC collapse, the old James company had been submerged — but maybe not quite without trace, for now Norton-Villiers rescued one of the old James model names, to dub the new twin the Commando.

Yet don’t dismiss the Pi 0 as a totally lost cause, for it (or to be more precise, its Z26 successor) did bequeath a feature or two to the Norton Commando. Primarily, of course, there was the big-backbone frame with its tank finish of silver, lined with black and Isolastic engine-gear mounting system; but there was also the use of Fischer Superblend main bearings (which have slightly barreled rollers) in Tony Dennis’s redesigned bottom-end assembly. Though the Commando did not at first use the Superblend bearings, they were adopted later as a means of overcoming Commando bearing problems.

Could AMC ever have produced the P10 in its original form? Very probably not, for tooling-up would have been very costly, and Plumstead were in financial difficulties even before the prototype reached tangible form. Besides, with that massive crankcase assembly (with cast-on styling motif on the covers) it represented a type of motorcycle that was already outmoded.