Forget all that nonsense about autocratic engineers and underhand boardroom shenanigans; Joe Public killed the British motorcycle industry. The fact that he kept buying their machines when they were so lamentably underdeveloped and so shoddily produced simply encouraged the manufacturers to keep churning out the same old porridge, with a face-lift here and a stop-gap there, year after monotonous year. And, why not? Joe, it seemed, didn’t want change, and shied away from innovation.

And so the British motorcycle industry was all right – all right that is, until the day when along came another motorcycle industry that wasn’t the least bit interested in what Joe wanted. They sold motorcycles to Joe’s sons and daughters who welcomed change with open arms, and that caught the British motorcycle industry on the hop – overnight it was too late, too late to change, too late to win the kids over. If you bought a Matchless G12, or a BSA B40, or a 750 Bonneville or a Commando, it was all your fault.

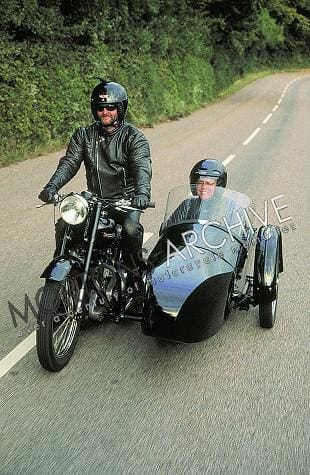

Strange thoughts to be having after spending an afternoon in the company of two devoted British motorcycle fans – no, that’s incorrect, two devoted Panther fans. Mary and Fraser from Chudleigh in Devon are the kind of people whose enthusiasm is so infectious it makes you want to rush home and comb the For Sale ads for a single cylinder sloper of your own. Listening to them talk about their 600cc Model 100, you wonder why you never did it before. The machine has a unique character, a beauty of line and a tangible charisma equal to that of a Pacific Class steam locomotive or an Empire flying boat. Sitting beside a country road in sunny late September, the light dancing off the polished black paintwork and chrome, the discernable aroma of warm machinery and engine oil in the air, it all makes perfectly good sense; but was there a future for it back in 1966?

Of course, the answer is, none whatsoever. That was the crunch year for the big four-stroke single from Cleckheaton, West Yorkshire, the flagship, and, by that time, almost the only product of Phelon and Moore (P & M) Ltd. Burman had stopped making the gearboxes and Lucas had stopped making the Magdynos, the magneto with piggy-back dynamo unit that provided the ignition spark and generated power for the six-volt electrics. And, contrary to what I said earlier, people had actually stopped buying Panthers.

It is rum oured, and possibly even true, that P & M had drawn up plans for an alternator-equipped engine, and other gearboxes were available, but if nobody wanted to buy a Panther, what was the point in carrying on? During more than 30 years of production, the Model 100 and its successor, the 650cc Model 120, had earned a formidable reputation as a sidecar hauler for the common man, but times had changed and the common man now aspired to personal transport with a wheel in each corner and a roof over his head. So P & M despatched one final batch of machines to their one-time major, and by then only remaining outlet, George Clarke Motors of Brixton, South London, and then shut up shop for good.

oured, and possibly even true, that P & M had drawn up plans for an alternator-equipped engine, and other gearboxes were available, but if nobody wanted to buy a Panther, what was the point in carrying on? During more than 30 years of production, the Model 100 and its successor, the 650cc Model 120, had earned a formidable reputation as a sidecar hauler for the common man, but times had changed and the common man now aspired to personal transport with a wheel in each corner and a roof over his head. So P & M despatched one final batch of machines to their one-time major, and by then only remaining outlet, George Clarke Motors of Brixton, South London, and then shut up shop for good.

In many respects it wasn’t such a bad ending for a saga that had begun at the tail end of Victorian England. Joah Phelon, the company’s founder, built his first motorcycle in 1900; four years later he was joined by Richard Moore. They established a partnership that regularly displayed levels of mechanical innovation and market awareness that were to make them formidable rivals in the highly competitive and, during the Depression years, starkly cut-throat world ahead. P & M’s individuality and single-mindedness are clearly mirrored in the bikes they produced, no more so than in the one particular model that appealed to both Mary and Fraser, and at different times.

Mary had always been a bike nut; her grandfather was assistant works engineer for BSA and rode a sloper outfit with two engines – one to run and one to fix. Mary’s mother always hoped that one day he would bring her home a Bantam, but he never did. Motorcycles were in her blood then, and when a college friend showed her a photograph of a chopped Panther in Back Street Heroes magazine, she made up her mind that one day she would own such a beast herself. Fraser, on the other hand, was never interested in bikes until he met Mary (sigh). Having passed his test, he bought and restored a BSA C12, which served as a gentle introduction to classic motorcycling, but it wasn’t until he was killing time on an Arctic expedition, thumbing through bike mags, that he, too, resolved to acquire a Panther.

Curiously, fortuitously, and by happy co-incidence, Mary and Fraser had both chosen the same machine – it had to be a Model 100, it had to have a rigid frame and it had to have telescopic front forks. So, with united resolve and a limited budget, they set about tracking one down. That, as is so often the case, took time; even joining the Panther Owners’ Club did little to improve their chances. No matter how far afield Panthers may have travelled in their earlier years, they all seemed to have gravitated back to the North of England. Meanwhile, ownership of a contraption now referred to as the ‘Mad Dneiper’ added a sidecar to their wish list.

Curiously, fortuitously, and by happy co-incidence, Mary and Fraser had both chosen the same machine – it had to be a Model 100, it had to have a rigid frame and it had to have telescopic front forks. So, with united resolve and a limited budget, they set about tracking one down. That, as is so often the case, took time; even joining the Panther Owners’ Club did little to improve their chances. No matter how far afield Panthers may have travelled in their earlier years, they all seemed to have gravitated back to the North of England. Meanwhile, ownership of a contraption now referred to as the ‘Mad Dneiper’ added a sidecar to their wish list.

Eventually, a tip-off from the Owners’ Club led to a damp shed in Bristol where they discovered the dismembered remains of a 1948 Model 100. Politely put, it was incomplete – a frame, forks and front wheel, an engine and a gearbox and lots of bits that, as they were to find out as work progressed, had nothing to do with Panthers at all. Nevertheless, it was a start; the assignment was accepted and a restoration, that was eventually to take four years, was under way – on the understanding that they removed a derelict sidecar chassis at the same time.

The frame and gearbox were corroded but serviceable, but where the engine had been sat on the floor the bottom of the crankcases had rotted through and inside the motor rust had taken a grip on every surface. Stripping it down, they discovered “Engine last rebuilt Bristol 1963 – D. Shotton” painted on one of the flywheels, suggesting an earlier project that had been abandoned; sadly, after all that time, the only components that didn’t need serious attention were the re-sleeved cylinder with its new piston.

By now familiar with the workings of the local classic bike grapevine, Mary and Fraser took their troubles down to Gold and Classics, a small garage in Exeter that served as, among other things, an enthusiasts’ drop-in centre. There, they were introduced to Bill Bowdage and John Clayton who they entrusted with the task of refurbishing the crankshaft assembly. Oversize big-end rollers from the Owners’ Club spares scheme compensated for the machining necessary to get rid of pitting on the crankpin. The Club also supplied new valves and valve springs, while Bill restored the exhaust flange threads on the twin port head. The cases were beyond repair, so replacements were purchased from another Club member. They are from a slightly later model, the difference being that they are designed to mount a Lucas Magdyno as opposed to a magneto only. Before 1952, the dynamo on Model 100s was mounted separately on the frame saddle post, chain-driven off the magneto below it. The give-away is the bracket cast into a frame lug underneath the rider’s seat, otherwise you’d never know.

By now familiar with the workings of the local classic bike grapevine, Mary and Fraser took their troubles down to Gold and Classics, a small garage in Exeter that served as, among other things, an enthusiasts’ drop-in centre. There, they were introduced to Bill Bowdage and John Clayton who they entrusted with the task of refurbishing the crankshaft assembly. Oversize big-end rollers from the Owners’ Club spares scheme compensated for the machining necessary to get rid of pitting on the crankpin. The Club also supplied new valves and valve springs, while Bill restored the exhaust flange threads on the twin port head. The cases were beyond repair, so replacements were purchased from another Club member. They are from a slightly later model, the difference being that they are designed to mount a Lucas Magdyno as opposed to a magneto only. Before 1952, the dynamo on Model 100s was mounted separately on the frame saddle post, chain-driven off the magneto below it. The give-away is the bracket cast into a frame lug underneath the rider’s seat, otherwise you’d never know.

With the engine apart, the unique aspects of its design were self-evident. Everybody knows that on a big Panther the engine takes the place of the frame front down tube, but you’d be forgiven for thinking that the immense size of the various components alone provides sufficient strength to keep chassis and soul together. Not so – two long U-bolts, inserted up through either side of the crankcase from points below the crankshaft, pass through the barrel and the cylinder head. Two forged brackets are then bolted to the top of the cylinder head and they are connected to the steering head by a single, one-inch diameter bolt. So effectively the bottom of the engine is supported by the headstock, not hung from the barrel that is hung from the cylinder head. These days this would be regarded as overkill gone mad, but don’t forget that metallurgy and frame technology have both come a long way since the design was laid out in 1933.

Then there’s the question of lubrication. That large, finned bulge at the front of the crankcases contains the engine oil, but not in the modern-day sense of a wet sump, or like the separate tank incorporated in the cases of a Royal Enfield; on the Panther the oil reservoir is separated from the crankcase proper by a weir with a gap at the top. Oil is pumped up to the inlet rocker spindle, the back of the cylinder and the timing case, and is then left to its own devices to find its way down into the crankcase via an external pipe from the front of the head and the pushrod tube. The spinning flywheels pick up the oil and fling it back into the reservoir.

Then there’s the question of lubrication. That large, finned bulge at the front of the crankcases contains the engine oil, but not in the modern-day sense of a wet sump, or like the separate tank incorporated in the cases of a Royal Enfield; on the Panther the oil reservoir is separated from the crankcase proper by a weir with a gap at the top. Oil is pumped up to the inlet rocker spindle, the back of the cylinder and the timing case, and is then left to its own devices to find its way down into the crankcase via an external pipe from the front of the head and the pushrod tube. The spinning flywheels pick up the oil and fling it back into the reservoir.

Such a simple system would be hard pressed to cope with the demands of many engines built in the early 1930s when the Model 100 was the new kid on the block, let alone anything post war, but it did, and still does, work. The secret of its success is, of course, hefty construction of engine components and low stress. Apart from the inlet rocker arm and the cylinder wall, all the bits, pieces and bearings within the engine rely upon what engineers euphemistically term ‘splash’ lubrication. Oil often has a habit of finding its way into the wrong places, but on the Panther this wanderlust is put to good use. Whipped around by the timing gears, lube coats the gear teeth, the camshaft lobes and the cam followers; it works its way quite successfully into the big-end and main bearings, and on the drive-side it passes through the inner main bearing to reach the outer bearing, which, of course, is sealed on the outside to prevent the primary chaincase from filling up.

The model’s relatively low performance and, more to the point, the customer’s expectations of a robust, no frills machine with plenty of low-down punch, were also taken into account when specifying the big end bearing. A two-row, un-caged roller bearing is used; doing away with the cage allows you to fit more rollers which in turn reduces the individual load on each roller – better for low speed slogging, without the danger of the rollers jamming together and skidding which only becomes a problem at high rpm, well above the Model 100’s peak power ceiling of 23bhp at around 5000rpm. And while we are on the subject of performance, consider for a moment that the engine was deliberately designed to produce maximum torque – for lugging double-adult sidecars and caravans up Ben Nevis no doubt – at a heady 3500rpm. Hence the use of two, 14lb flywheels, a flat-topped piston, interchangeable inlet and exhaust valves and a carburettor with a 40-degree up-draught.

The model’s relatively low performance and, more to the point, the customer’s expectations of a robust, no frills machine with plenty of low-down punch, were also taken into account when specifying the big end bearing. A two-row, un-caged roller bearing is used; doing away with the cage allows you to fit more rollers which in turn reduces the individual load on each roller – better for low speed slogging, without the danger of the rollers jamming together and skidding which only becomes a problem at high rpm, well above the Model 100’s peak power ceiling of 23bhp at around 5000rpm. And while we are on the subject of performance, consider for a moment that the engine was deliberately designed to produce maximum torque – for lugging double-adult sidecars and caravans up Ben Nevis no doubt – at a heady 3500rpm. Hence the use of two, 14lb flywheels, a flat-topped piston, interchangeable inlet and exhaust valves and a carburettor with a 40-degree up-draught.

Once everything was cleaned-up and serviceable, engine rebuilding was a straightforward matter of methodical reassembly with all the necessary gaskets and a set of shiny stainless case screws and a push rod tube from the Club spares scheme. A Magdyno was tracked down at an autojumble during a visit to family relatives in Chester and a new Monobloc carburettor with hard chrome sleeve was fitted in place of the period remote float unit. Thinking ahead, and no doubt in view of his riding experience with the 250 Beeza, Fraser had the dynamo rewound to support 12-volt lighting – it puts out 60 watts via a solid state regulator tucked away in the toolbox.

‘A two-row, uncaged roller bearing is used; doing away with the cage allows you to fit more rollers which in turn reduces the individual load on each roller – better for low speed slogging…’

Then, with the engine fit for use, it was time to pay the gearbox a visit. Old Burman boxes relied on grease, not oil, for lubrication – not good for snappy gear changing, but an excellent idea if you plan to leave them in a damp shed for 30 years as Mary and Fraser discovered, much to their relief. However, with all the congealed gloop cleaned out, they took some advice from the Owners’ Club and opted to fit a spares scheme seal on the left-hand end of the main shaft and run the box on EP90 oil.

With everything seemingly going so well, now is as good a time as any to raise the dreaded spectre of cycle parts. Once again, membership of the Owners’ Club proved invaluable, turning up the mudguards and a toolbox, but finding a suitable rear wheel was difficult, more so because P & M used a Royal Enfield hub which incorporated a cush drive. And the most elusive component? The rear brake pedal, would you believe? They must have looked at dozens, any one of which might have done the job, almost, but having no pattern to work from proved a major stumbling block. Eventually a pedal was located on Orkney – through the Owners’ Club, of course!

The frame was powder coated and everything else that needed it was treated to a coat of black, two-pack paint. Originally, the petrol tank would have been chrome plated with cream panels, but Mary and Fraser agreed that theirs was to be an all-black machine. They did, however, keep the wheels to the standard 19in rim size, retaining the 8in rear and 7in front brakes as produced by the factory. Later Model 100s fitted a bigger front brake, but they also had swinging arm rear suspension and conventional telescopic forks, all of which could be regarded as too mainstream by a dedicated Panther fan.

The frame was powder coated and everything else that needed it was treated to a coat of black, two-pack paint. Originally, the petrol tank would have been chrome plated with cream panels, but Mary and Fraser agreed that theirs was to be an all-black machine. They did, however, keep the wheels to the standard 19in rim size, retaining the 8in rear and 7in front brakes as produced by the factory. Later Model 100s fitted a bigger front brake, but they also had swinging arm rear suspension and conventional telescopic forks, all of which could be regarded as too mainstream by a dedicated Panther fan.

In 1948, give or take a year, P & M shed their pre-war, girder front fork look with the adoption of Dowty Oleomatic suspension, which is far too quirky an option to be passed-up if you have the chance. The Dowty fork is an upside-down design – the lower legs slide inside the upper stanchions – but the real trick is in the springing which is done by pressurised air. You literally blow the forks up through a valve in the top yoke, extending the legs until a register mark on the slider aligns with the lower edge of the fork cover. And away you go, just as long as the seals hold, that is.

Guarantee of success

In this instance, the seals didn’t hold, and rather than wrestle with refurbishment that held no guarantee of success, Mary and Fraser opted for the popular alternative of a pair of internal springs from the Panther fork that replaced the Dowty. Panther folklore upholds their decision; accuracy of machining as well as wear and tear all have a part to play, but at the end of the day you either have a pair of forks that stay up, or a pair that don’t. Leaving the bike unused for a couple of weeks, then finding the forks flat, could be a nuisance on a regular basis, but having them deflate instantly when you hit a pothole in Tesco’s car park is not a laughing matter – especially when you have a sidecar full of frozen food. P& M were not the only company to fit Dowty Oleomatic forks – Scott and Velocette did too, but the novelty was short-lived. The consensus of opinion is that they relied too much on regular owner maintenance, were expensive to produce and, as might be expected, were expensive to repair. Interestingly, Dowty, who built aeroplane undercarriages during the WWII, are still in business today supplying landing gear for the Airbus range of aircraft. What a shame that a little of their success didn’t rub off on Panther, Scott and Velocette.

Back in the real world, Mary and Fraser moved house, built themselves a garage, laid out some cash on a part-exchange speedometer, a headlight from India with a halogen bulb and pair of exhaust pipes from Armours, and finally rolled-out the Panther. To start with they rode it as a solo, but straight away they had overheating problems and the exhaust valve nipped-up. The culprit was the finning on the cylinder head or, to be exact, the lack of finning on the cylinder head. Thanks to corrosion, the fins were ‘like razor blades’, and razor blades were clearly not up to the job. Fortunately (yes, you’ve guessed it) the Owners’ Club were able to supply a new head and with that in place the Model 100 ran sweet as a nut. Only one thing was now missing.

The choice of sidecar was to be as important as the choice of bike, and since the early post-war Model 100 was selected for its aesthetic appeal – ‘it looks just like the leaping panther in the Company logo’ – the shape of the sidecar had to be equally potent. Much exhaustive research and angst later, all fingers pointed to a Watsonian Avon, no substitutes accepted, which proved to be an extremely lucky choice since the body of just such a sidecar soon appeared in the local Free Ads. Barn stored in Slapton, Devon, it was in only slightly better condition than the Sherman tank dragged up from the seabed in that neck of the woods, but by now you will have realised that our happy duo are not fazed by any undertaking.

The choice of sidecar was to be as important as the choice of bike, and since the early post-war Model 100 was selected for its aesthetic appeal – ‘it looks just like the leaping panther in the Company logo’ – the shape of the sidecar had to be equally potent. Much exhaustive research and angst later, all fingers pointed to a Watsonian Avon, no substitutes accepted, which proved to be an extremely lucky choice since the body of just such a sidecar soon appeared in the local Free Ads. Barn stored in Slapton, Devon, it was in only slightly better condition than the Sherman tank dragged up from the seabed in that neck of the woods, but by now you will have realised that our happy duo are not fazed by any undertaking.

The wooden framework was completely rotten and served only as a pattern for Fraser to make a completely new structure from ash, bought locally on the Marsh Barton trading estate. In contrast, most of the metal panels were reusable, galvanised steel sheet being used where necessary to make good. The framework is held together with stainless screws and, on the underside, the bodywork is pinned with copper nails. Mary undertook the upholstery with materials from Exeter Vehicle Trimmers. The finishing touches, the handles, the rack on the boot lid for a hamper and the Watsonian transfers, were supplied by Charnwood Classic Restorations in Leicestershire. Now all they needed was something to fix it to.

While musing on this very problem, Fraser happened to glance out of the kitchen window and notice the half buried remains of the chassis they had dragged home from Bristol with the bike parts all those years ago. With nowhere to store it, it had been left in the garden and earth had been piled over it when the footings for the garage had been dug. A quick inspection confirmed that the tube work was still intact, the mudguard was sound and even the wobbly-wheel still wobbled, but the wheel bearings were well past their sell-by date. Den Lugg, another Gold and Classics contact, was consulted; new bearings to the same specification were going to cost more than £300, so the spindle was machined to accept metric alternatives. Den dug out some suitable sidecar fittings and rebuilt the bike’s front wheel with heavy-duty spokes while Fraser laced-up the sidecar wheel. The task of assembling bike, chassis and sidecar was, apparently, quite straightforward and not the black art some people would lead you to believe. “You’ll find details in any of the old motorcycle handbooks; just find yourself a flat surface, two builders’ planks, a spirit level and a tape measure and you’re away.” Maybe.

So, has the Panther outfit lived up to expectations? As a solo the bike was ‘brilliant, but not happy over 70, now it is ‘simply fantastic’. You have to admit that it’s a fine example of a classic machine, packed with idiosyncrasies that leave most post-war parallel twins in the shade. Like those Dowty front forks, and the starting procedure that requires the use of the half-compression lever on the right-hand side of the crankcase to ‘reduce the lethality of kick-back’. My particular favourite is the rear stand that could have been designed by Brunel – “A bridge for the Avon Gorge, no problem; an iron-hulled passenger liner, I have the plans here; a rear stand for a Panther motorcycle, my pleasure!”

So, has the Panther outfit lived up to expectations? As a solo the bike was ‘brilliant, but not happy over 70, now it is ‘simply fantastic’. You have to admit that it’s a fine example of a classic machine, packed with idiosyncrasies that leave most post-war parallel twins in the shade. Like those Dowty front forks, and the starting procedure that requires the use of the half-compression lever on the right-hand side of the crankcase to ‘reduce the lethality of kick-back’. My particular favourite is the rear stand that could have been designed by Brunel – “A bridge for the Avon Gorge, no problem; an iron-hulled passenger liner, I have the plans here; a rear stand for a Panther motorcycle, my pleasure!”

Certainly there will be little glitches and things to be done, but then there always will be if you want to put miles on your machine – something that the Panther Owners’ Club encourages and Mary and Fraser are keen to do. It had a rebore last winter, not that it stopped the engine burning oil as apparently all Panther big singles do, just that it reduced consumption to a very laudable 300 miles to the pint (200 miles is generally thought to be good). Then only recently, the crankshaft pinion that drives the camshaft shed a tooth – it didn’t affect performance and Fraser only discovered the broken part in the timing case when he took the cover off to adjust the magneto pinion shimming. And the camshaft is getting a bit worn, so something will have to be done about that soon.

Otherwise, all is well; it would be nice to think that Mary and Fraser and their leaping beast of an outfit will make it up to Cleckheaton sometime soon to visit the old factory. It still stands, deserted now and due for demolition, after 60-odd years of motorcycle production and a further 20 as the home of Samuel Birkett Ltd, manufacturers of valves for North Sea pipelines. Am I being a little bit over-nostalgic here? Maybe, but it’s a cracking excuse to get the bike out!

Pics courtesy of Phil Mather