One of only three Model 95s that the Panther Owners Club is aware survives. Sandy Bloy’s example is a great study in restoration, while keeping a bike’s story on its sleeve.

Words and photography by Stuart Urquhart

I first set eyes on this month’s build feature – a gorgeous 1939 Model 95 Panther – on a visit to Sandy Bloy’s classic bike emporium in Perth. Otherwise known as a ‘Redwing’ model, I was struck by this Panther’s lovely patina, ageing paintwork and tarnished chrome. The Redwing-embossed timing cover is another marvellous detail; so too is the sump’s oil filler cap with its winter/summer oil recommendations forever engraved onto its brass top. The petrol tank’s faded coach lines, its antique cream paintwork and tarnished chrome are other delights – as are the Panther-embossed tank rubbers moulded by none other than John Bull.

I was not surprised to learn that heads turn whenever and wherever this appealing motorcycle is encountered. From a bygone age, it is a very rare machine indeed. According to the Panther Owners Club, there are only three Panther 95s registered in the UK, Sandy’s being number three. This important and historical motorcycle still has its original buff log book and registration number, and both the engine and gearbox numbers are Panther club verified. When I learned from Sandy that he and his good friend John Lamb rebuilt it from the ground up, I naturally pestered Sandy for its story…

“When I bought the Panther from John, the engine was in the frame, although I would describe it as in a wobbly rolling chassis state,” he said. “That is to say that numerous bits and pieces were loosely attached – so it might be considered more of a dry build. Before the Sunbeam 95 came to me, it had a Burman GP box. However, John discovered the 95’s correct Burman BAP gearbox had been mistakenly fitted to a ‘51 Panther 100 that he’d acquired from the same source – amazing! John simply swapped the gearboxes over so the correct gearbox came with the bike.

“I also remember that the exhaust pipe was beyond service, the silencer was missing, and the mudguards were riddled with holes. The rear mudguard was only fit for a skip and the Millar magneto and dynamo looked tired and in need of attention.

“However, John assured me that most parts were with the bike and that it would be a fairly simple task to rebuild and put it back on the road – especially given our combined skills.”

An interesting history

According to John, the Panther 95 once belonged to David Gow, a respected engineer with P&M from 1927 to 1933. David bought the Panther from his employer and reputedly developed a sprung sidecar which was later adopted by Panther. He is also credited with developing a swinging arm frame that once again was adopted by P&M, and then adapted by work colleagues. According to John, David left Panther in about 1933 to set up a motorcycle business in Edinburgh. He then moved to Auchterarder in Fife before settling in Stanley, Perthshire, during the late 1960s.

Around this time, David’s original prototype swinging arm Model 100 (plus several other Panthers) was purchased by a local VMCC member, a colleague of John’s. After John had restored a Big 4 Norton for his VMCC friend, the Model 95 then came to him as payment.

For many years the 95 remained with John, untouched and in need of some fettling. When Sandy saw the neglected Panther, he offered to buy and restore it and, as part of the deal, Sandy persuaded John into lending a helping hand with the rebuild. Of course, John wholeheartedly agreed and the 95 changed hands.

“John is a highly skilled restorer and I was grateful for his help,” said Sandy. “He has helped me with many rebuilds and has an in-depth knowledge of prewar motorcycles, having had countless throughout his life – some of which are still with him today.

“A bonus was that at some point David Gow had comprehensively rebuilt the 95 engine and it looked absolutely mint inside.”

A sympathetic restoration

Both Sandy and John admired the 95’s patina. Wisely, they agreed to sympathetically rebuild it rather than comprehensively restore it. “Rebuilding the Panther in its rustic condition was the right choice,” said Sandy. “We both agreed it would be sacrilege to lose the wonderful history that was indelibly stamped all over the machine. Some restoration work would be required, but the Panther looked beautiful in its antique condition – even chrome parts had taken on a timeless quality that would be spoiled by the introduction of new parts.”

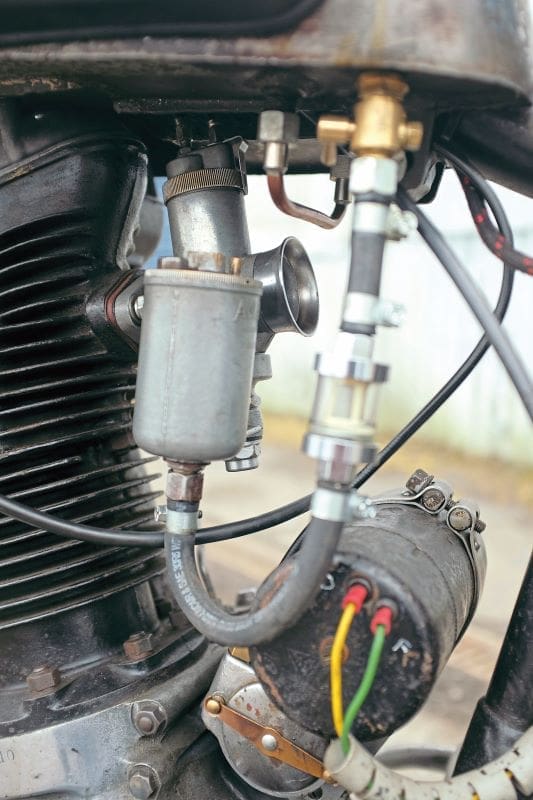

Meantime, Sandy sent the magneto and dynamo to be reconditioned by specialists DH Hay. John had already established that the inimitable Miller ammeter was working, as were several other electrical parts. However, the bulbs and the wiring harness were replaced, along with a new voltage control unit and battery.

“I remember the 7in headlamp caused a bit of confusion with its overly high position and long mounting brackets. I thought it was the wrong type, but while researching old photographs I realised that the horn was mounted below the headlamp – hence the gap. The lamp reflector required a new glass. A replacement was found after a quick rummage through my boxes of spare parts,” grinned Sandy.

John then suggested that a Velocette exhaust pipe might be a good substitute for the Panther’s grotty-looking down pipe, and better than a bright and shiny new one from Armours. On John’s next visit he was presented with a nicely aged Velo pipe that Sandy had found in his parts bin, so John obligingly machined and welded on the required flange to permit its fitting to the Panther. Then a decent Burgess silencer was conjured up from Sandy’s ‘magic’ bin.

“John next attended to some fabrication work on the corroded front mudguard, carefully brazing and filling holes so as to retain its rustic look. The rear guard was deemed to be scrap so John reworked a Wassell mudguard, cut it to the correct length, and made a replica working hinge to facilitate rear wheel removal. Then he made up working pins and rivets – it was a proper job!” Sandy beamed. “John then made up a missing return spring and retaining bolts for the rear stand. The stand has clever ‘rocker feet’ that make its deployment a delightful one-handed pull; I wish more prewar rear stands were as effortless to operate. The girder forks received new bushes and spindles, again all fabricated by John.

“The original chrome petrol tank was de-rusted before a sealing coat of lacquer was applied to preserve its outer patina. Then I removed the wheels from the rolling chassis to service the hub bearings and brakes. The pre-monobloc carb was thoroughly cleaned and appeared to be in good condition so, after a service, on it went. Then we fitted the mag-dyno, set the tappets, and timed the engine. I added fresh fluids and a new battery before John whispered, ‘Let’s see if we can start her up.’ I was more than a little excited.”

Test run – and a missed opportunity

“I flooded the carb and eased the engine past compression by using the unique foot-operated cam-lifter attached to the timing cover. I was flabbergasted when it fired up after the first kick! Even more so when the warming engine settled into a Panther’s characteristically quiet and slow tickover,” chuckled Sandy. “I was also surprised by its exhaust note – different than a standard Panther’s thud-thud-thud, it sounded crisper. I wondered if this was a result of the rebuilt engine, or perhaps the Burgess exhaust I’d fitted.

“The ride turned out to be quite pleasant, although initially I felt uncomfortable and crouched due to my larger-than-average physique! So John modified the seat by fabricating a new set of front and rear mounting brackets. When fitted, the brackets allowed the seat to be moved back by a full 2.5in, which vastly improved rider comfort – so well, in fact, that John subsequently carried out the same mod to his own Model 100. Rider comfort is further enhanced on the Model 95 by rubber mounted handlebars that effectively isolate the rider’s hands from engine vibration. Now I can happily boast that the 95 is very comfortable indeed!

“The clutch and transmission performed as well as any prewar bikes I’ve owned. The handling and improved Enfield brakes also performed as expected – allowing for some engine-braking assistance on some of Perthshire’s steeper descents.

“With John’s invaluable help, I enjoyed restoring this old girl so much. It really turned out to be a labour of love!”

Due to Covid, I missed Sandy’s test run and the opportunity of a ride before he sold the Panther to Verralls Motorcycles. If you fancy owning this fabulous machine, you might want to beat a hasty path to its big green door in West Sussex.

Panther Model 95 SPECIFICATIONS:

Engine: 490cc OHV with enclosed valve gear Bore & stroke: 79 x 100mm Compression: 7.0:1 Power: 25hp @ 6000rpm Gearbox: Burman 1 BAP (later pattern) Fuel tank: 2 and 5/8ths gallon Front fork: P&M Brampton Webb HD Frame: P&M Diamond 350 pattern Wheels: 3.25in x 19in Brakes: Enfield 8in modified hubs Weight: 365lb

P&M and Panther Motorcycles – the history

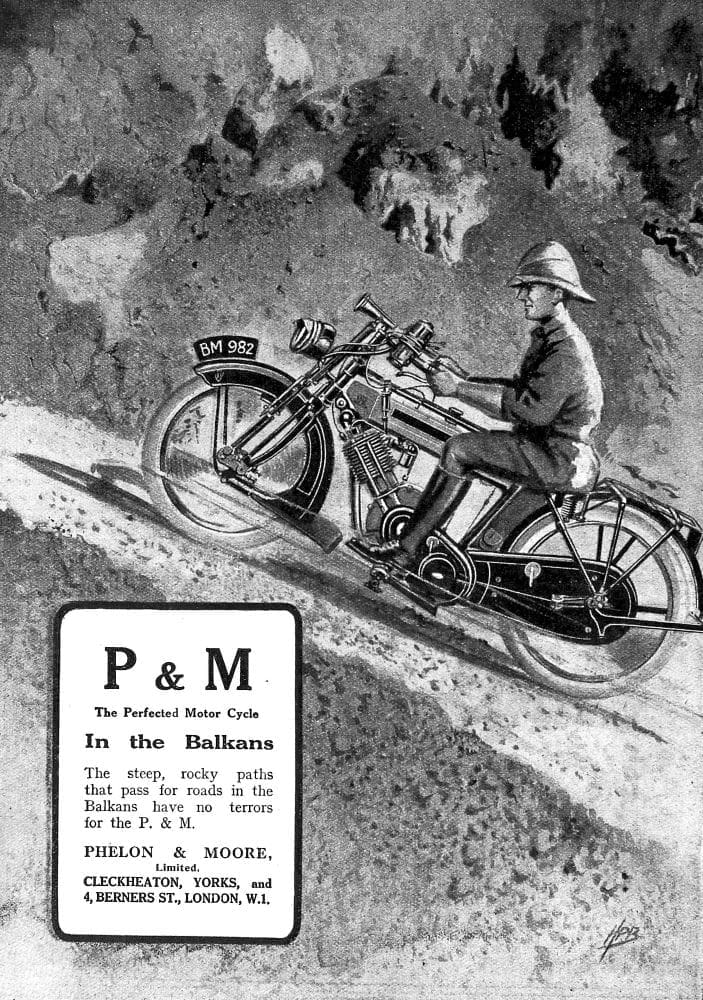

Phelon & Moore began making bicycles before the turn of the century and were destined to become a household name by producing ‘The Perfected Motorcycle’. P&M developed a range of Panther-branded single-cylinder motorcycles at its Cleckheaton factory during the early 1920s. The company became renowned for the design and manufacture of its ‘sloper’ style, large capacity, single cylinder motorcycles.

P&M also experimented with a V-twin prototype as early as 1914. Unfortunately, at the outbreak of war the factory was forced into producing solo motorcycles for the war effort. The V-twin was subsequently shelved, only to be withdrawn later.

The first Panther was launched in 1921, but it was the mid-1930s Model 100 (600cc) and later 1960s Model 120 (650cc) that brought fame and success. Panthers were renowned as excellent and reliable workhorses, best tasked to pulling a family sidecar.

The Panther won admirers with its unusually low tick-over, often described as ‘firing once every lamp post’. This was largely credited to the engine’s massive flywheels and quality engineering. Simple and robust motorcycles, they were hugely popular due to their distinctive looks and colossal OHV inclined engines. Being of excellent design, cheap to run, and exceptionally simple to service, Panthers soon attracted a loyal following. It is no small wonder that many of the later high-capacity bikes are still in use.

Phelon & Moore became generally known as Panther Motorcycles in about 1930. In 1932 the company launched a range of popular lightweight 250cc (Model 40) and 350cc (Model 45) motorcycles, which became generally known as the Red Panther range. Improved models followed and a team of P&M riders on competition 250cc models competed successfully at the Scottish Six Day Trials. In 1934 a Model 40 won the Maudes Trophy, which resulted in The Stroud, a full-on competition trials machine.

During the postwar 1950s, P&M developed a successful 197cc (Villiers engine) lightweight in two guises: the Model 10/3 and Model 10/4. These were simply three-speed and four-speed versions of the same machine and enjoyed a production run of six years.

During the scooter craze of the 1950s and 1960s, Panther imported a scooter from French manufacturer Terrot. However, this became responsible for countless warranty claims and damaged Panther’s reputation. Although Panther went on to develop its own scooter, known as the Panther Princess, it was a costly exercise and suffered from poor sales. The venture failed and the arrival of the cheap family car helped bring about the demise of P&M as a motorcycle manufacturer. Motorcycle production limped on until 1966, before P&M was forced into receivership and closed.

Strength and endurance

Pioneering motorcyclists Florence Blenkiron and Teresa Wallach rode a 1934 Model 100 combination on an epic trans-African crossing from Algiers to Cape Town – thus the Panther became the first motorcycle to cross the Sahara desert.

In February 1939, as an official demonstration of British engineering and reliability, the much-publicised ACU test of Turner’s new Triumph twin took place. Not to be outdone, P&M picked up the gauntlet…

In a similar publicity stunt, P&M devised a test of ‘Unparalleled Endurance and Severity’ for its Panther singles. In association with ACU officials, a Panther 100 was chosen from the production line and methodically checked. The chosen single would then be ridden from London to Leeds and back, continuously, day and night, for 10,000 miles. ACU official riders devised a relay system and set off from London at 6am on March 23, 1939.

Although the test Panther suffered some minor faults, it successfully completed the endurance test. According to a euphoric motorcycling press, even gales, hail and snow failed to hamper the Panther’s progress. The ACU reported that the 600cc Panther 100 Model travelled a total of 10,017 miles in 209 hours and 49 minutes at an average speed of 40mph, consuming fuel at a rate of 56.88mpg. It was declared as an amazing feat for a prewar motorcycle!

A short production run

Based on its 600cc Panther 100 Model, P&M introduced the 500cc Model 95 single in January 1938. Designed as a solo machine, the new 95 received the Model 85 diamond lightweight (350cc) frame – into which it was possible for P&M engineers to squeeze a 500cc sloper engine. The Model 100’s larger fuel tank was also added.

The Model 95 benefitted from Enfield’s better-performing hubs and brake drums. As with the other large-capacity Panther singles, the new 95 had the Redwing logo cast into its timing cover, along with a restyled model identification number.

Several key differences in the Model 95 engine (compared to previous models) were that Panther departed from its long-established practice of utilising the engine as a ‘stressed member’ and developed a single port rather than the twin port cylinder head of the time.

The 95’s change to a ‘spigot-flange’ cylinder barrel departed with the long-established practice of holding down the head and barrel by means of four long through studs that extended all the way from inside the crankcases to the top of the cylinder head. Other changes included a redesigned cast iron cylinder head and rocker box with a polished alloy rocker cover.

The combination of the significantly lighter frame and a free-revving 500cc engine (i.e., 25hp @ 6000rpm as opposed to the 600cc Model 100’s 25hp @ 5000rpm) resulted in better handling and a more ‘sporting’ ride.

Unfortunately, the 95’s production run lasted only two years, with less than a few hundred leaving the factory.