Pip Harris’s new Featherbed Manx arrived late in 1952, and when fitted as usual with a Watsonian sidecar, it proved faster than his old one. In fact, with the exception of Eric Oliver’s specially prepared Norton, the only outfit even quicker was Ted Davies’ works Vincent. Pip, who was whippet-thin in those days, surmised he was now being limited by the size of his passenger – Charlie Billingham – who had been with him from the start.

He admits that Billingham’s bulk had been an advantage when trying to keep all three wheels of the old Grindlay outfit down on the grass, but on Tarmac he felt that Charlie had become a handicap, and asked him to lose weight. “He either couldn’t, or wouldn’t,” Pip says, “and so we parted company fairly amicably and he began to passenger for Jack Beeton. Charlie still lives locally and we see each other occasionally, but I don’t think he ever really came to terms with me saying I could do better without him.”

In the short term Billingham had a point, as Beeton achieved three top-seven finishes in the Isle of Man between 1954 and 1956, while Pip was passengered in turn by Henry Mykos and Graham Holder, both of whom departed acrimoniously after promising starts, feeling that they deserved a bigger reward for their efforts. Perhaps they did, for passengering wasn’t always a bed of roses. Pip admits that on one occasion he ‘tipped Mykos out of the chair’ and didn’t wait for the ambulance men to finish attending to him before saying; “Just pick him up and put him back in the sidecar.” And in the 1954 TT, Pip was having a tremendous dice with Oliver, Hillebrand and Noll, when his brakes failed trying to match the hydraulic stoppers on the latter’s BMW, and he rammed the bank at Morney Three, pitching Holder over the front.

In the short term Billingham had a point, as Beeton achieved three top-seven finishes in the Isle of Man between 1954 and 1956, while Pip was passengered in turn by Henry Mykos and Graham Holder, both of whom departed acrimoniously after promising starts, feeling that they deserved a bigger reward for their efforts. Perhaps they did, for passengering wasn’t always a bed of roses. Pip admits that on one occasion he ‘tipped Mykos out of the chair’ and didn’t wait for the ambulance men to finish attending to him before saying; “Just pick him up and put him back in the sidecar.” And in the 1954 TT, Pip was having a tremendous dice with Oliver, Hillebrand and Noll, when his brakes failed trying to match the hydraulic stoppers on the latter’s BMW, and he rammed the bank at Morney Three, pitching Holder over the front.

By then the Featherbed frame – which, to be fair, Norton never promoted as a sidecar machine either on or off the track – had undergone fairly drastic modifications that included different fork yokes, smaller wheels and different gears. And luckily for Pip, that was when Ray Campbell bluffed his way into the chair – saying how good he was, when he’d actually never raced before. The two hit it off immediately. “Ray was brilliant,” Pip enthuses, “We raced together for many years and never had a disagreement. He didn’t even live very near to home, so we travelled separately, but I’d just say where we were racing the next weekend, and he’d be there without fail.”

With the right passenger and almost the best machine, things were really coming together, and the team was earning real funds. Graham Walker, for instance, paid them £50 start money – equivalent to several weeks’ wages – merely to start at a Silverstone meeting. And sponsorship by firms like Dunlop, Ferodo, Castrol and Esso totalled over £1500 per year! Pip’s chance to show what he could do with the very best engine – and proof that it really was faster – came at the end of the 1954 season, when Eric Oliver was sidelined with a broken arm. Rather unexpectedly in view of their rivalry – although hindsight indicates that it was probably because he was contemplating retirement – Oliver allowed Pip to borrow the short-stroke engine from his outfit that was languishing at Watsonian, provided Norton’s management didn’t get to hear about it.

During the next four races Pip had three wins and reckons he only came second in the fourth event because he missed a gear. So he’d proved his point, but the episode also confirmed his feelings about Oliver, whose surprising generosity proved to have a hidden edge to it when Pip returned the engine, and was presented with a bill for £42! “If I’d been racing, you’d have come second each time,” claimed Oliver, “so I’ve worked out how much extra you made by getting three firsts with my engine.”

During the next four races Pip had three wins and reckons he only came second in the fourth event because he missed a gear. So he’d proved his point, but the episode also confirmed his feelings about Oliver, whose surprising generosity proved to have a hidden edge to it when Pip returned the engine, and was presented with a bill for £42! “If I’d been racing, you’d have come second each time,” claimed Oliver, “so I’ve worked out how much extra you made by getting three firsts with my engine.”

Somewhat disenchanted with not receiving the same assistance from Norton, even after Oliver had effectively retired, Pip must have been encouraged in 1955, when he was finally offered a little works support from Matchless. Oddly, it came via the trade rather than the manufacturer, and at the Bemsee (BMRC) Annual Dinner it was the Mobil representative who asked him if he’d like a works G45. Naturally, he said yes, and bizarrely found that while the engine was free, he had to pay for the gearbox! Rated at 60bhp, the G45 gave five or six more horsepower than the Norton, but although he used it for four months, and finished third in the 1955 TT, Pip was never very happy with its characteristics.

He decided to return to his own Norton, and after he’d had achieved second place in the 1956 TT, he asked MD Gilbert Smith for a short-stroke works engine to use in it. In a final display of industrial intransigence – all the more inexplicable now their biggest sidecar star had departed the scene – Smith claimed this was impossible. Luckily, a major Yorkshire dealer overheard the conversation and interrupted with something like; “If you can’t find an engine for Harris, you needn’t bother finding the 50 Nortons I’ve got on order.” Strangely enough, the short-stroke motor was delivered almost immediately!

Unfortunately, the long wait didn’t produce the desired effect, as the motor didn’t prove very reliable. In fact the long wait meant the Manx had had its day as a sidecar machine. As a solo the frame’s capabilities could still make for a shortfall in power, but that advantage was naturally lost when the third wheel was added, and the tall motor didn’t lend itself to the lower and more streamlined outfits now emerging.

Unfortunately, the long wait didn’t produce the desired effect, as the motor didn’t prove very reliable. In fact the long wait meant the Manx had had its day as a sidecar machine. As a solo the frame’s capabilities could still make for a shortfall in power, but that advantage was naturally lost when the third wheel was added, and the tall motor didn’t lend itself to the lower and more streamlined outfits now emerging.

On the continent, all the top drivers had switched to BMWs, and the boxer twins were sweeping all before them, being powerful, reliable, and with a layout ideal for the genre. Pip decided that if he couldn’t beat them, he’d have to join them, so he and fellow charioteer Jack Beeton purchased a BMW race engine from Australian racer Jack Forest. Pip went over to Germany to have the engine rebuilt and to buy a new Rennsport race frame for it. “They did everything while I was there,” he recalls, “and were incredibly efficient. They were also extremely expensive, charging an astronomical £1500 in a bill that even included the petrol they’d used to wash the parts!” The would-be partners shared the initial cost, but it quickly became apparent sharing an outfit wasn’t going to work, so Pip bought out Beeton’s share and became the sole user.

The Rennsport frame was intended for solo racing, and like the Featherbed it proved less than ideal when hitched to a Watsonian chair in the sidecar class, where the trend – started by Eric Oliver – was towards ever lower and more integrated outfits. Never claiming any great mechanical or developmental skills, Pip again decided he had to follow fashion. “I basically set the engine, and myself, between the wheels, and asked my brother John to join everything together.”

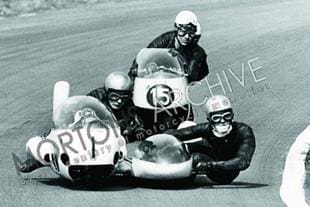

The result, brazed up in Reynold’s 531 tubing, and developed over the next few seasons was devastatingly successful. Pip didn’t even have any trouble converting to a kneeler chassis, after years in the saddle. “On the contrary, it seemed very easy,” he says, “I felt part of the machine, and it seemed really natural to drift it round corners.” The effectiveness of Pip’s BMW outfit, aided by passenger Ray Campbell, can be judged by the way it led the TT for several laps until the drive shaft broke. And he had similar combination of form and bad luck in a late-1950s Dutch TT, when only a dropped valve deprived him of a win.

The result, brazed up in Reynold’s 531 tubing, and developed over the next few seasons was devastatingly successful. Pip didn’t even have any trouble converting to a kneeler chassis, after years in the saddle. “On the contrary, it seemed very easy,” he says, “I felt part of the machine, and it seemed really natural to drift it round corners.” The effectiveness of Pip’s BMW outfit, aided by passenger Ray Campbell, can be judged by the way it led the TT for several laps until the drive shaft broke. And he had similar combination of form and bad luck in a late-1950s Dutch TT, when only a dropped valve deprived him of a win.

But that was the scene of what was perhaps his greatest triumph in 1960, when he was the first Briton to win in the Netherlands, and he did it against the top Continentals with their more powerful works engines. It was evidently an action-packed duel during which Fritz Scheidegger shunted the Harris outfit, loosening a carburettor float bowl (which Ray Campbell bravely held in place for the rest of the race!) and Pip only got past Florian Camathias by taking to the grass after overcooking things at the hairpin.

Despite always being one step behind the Continental riders when it came to machinery, Pip is full of praise for the BMW engines and their makers. “I lost touch with the factory when my initial contact, Muller, had a heart attack and retired,” he says, “but it didn’t really matter because the long-stroke engine was incredibly reliable.” A good example of the difference between the German factory, and the English ones he’d been used to, came when Pip’s engine seized in practice for the 1960 TT. Geoff Duke contacted the factory on his behalf, and they flew a crank, barrel and pistons to the Isle of Man in time for him to take part in the race! And then BMW star Helmut Fath rebuilt Pip’s engine free of charge, after which he and Pip rather appropriately had a one-two in the race itself.

With results like the TT and the Dutch under his belt, Pip feels he might well have been offered a works ride if there hadn’t happened to be so many European aces around. As it happened, stars like Camathias, Scheidegger and Fath were just three of an amazing batch of aces that also included Max Deubel, Klaus Enders, Horst Owesle and others. The result was that each year between 1959 and 1967 all of the first five places in every World Championship were occupied by BMW-powered outfits, and in the 22 years after 1953 continental racers with BMWs won the championship no fewer than 20 times!

With results like the TT and the Dutch under his belt, Pip feels he might well have been offered a works ride if there hadn’t happened to be so many European aces around. As it happened, stars like Camathias, Scheidegger and Fath were just three of an amazing batch of aces that also included Max Deubel, Klaus Enders, Horst Owesle and others. The result was that each year between 1959 and 1967 all of the first five places in every World Championship were occupied by BMW-powered outfits, and in the 22 years after 1953 continental racers with BMWs won the championship no fewer than 20 times!

Pip’s engine was naturally outclassed by the short-stroke works jobs used by these top men, and it wasn’t until 1969 he got his hand on one that had previously been used by Georg Auerbacher. It was too late to transform the situation, though, as domestic racers like Chris Vincent could now get more power from their 650cc engines, and Helmut Fath’s four cylinder URS was even outclassing the BMWs in the GPs.

Pip was also beginning to feel some of the drivers had barely enough skill to control their faster outfits, and he wasn’t too keen on sharing the track with them. Throughout his career, he’d actually been fairly lucky as regards accidents, apart from a serious one in 1963 when he was dicing with Chris Vincent at Snetterton. On that occasion he admits to trying too hard with the result the outfit up-ended at Riches, and he remembers flying through the air expecting the worst, only to have a surprisingly soft landing. This, he subsequently discovered, was because he’d landed on top of poor Ray Campbell, but he still broke a vertebrae, and lost almost a whole year’s racing with restricted movement in his left arm caused by a trapped nerve.

An even more decisive incident occurred at Cadwell in 1971, when Pip had ‘a bit of a crash’ and the long-suffering Campbell broke one wrist and badly sprained the other. Understandably, Ray decided to call it a day, and although Pip subsequently had some enjoyable races with John Thornton in the chair, trade support was dwindling and he decided to retire while he was still solvent and in one piece. It was probably a wise decision, as his first marriage had foundered with the pressures of work and racing, and about this time he met and married his present wife Anne. The couple, plus their two children, Peter and Ruth, have enjoyed a much more stable life than would have otherwise been possible. And the small farm which became the family home has enabled Peter Junior to pursue an interest in horses that has led to him becoming a top-class show jumper.

During his racing career Pip had continued running the family garage in partnership with a school friend. Sales of Esso petrol had proved lucrative, and a Mazda car agency had also been successful, so Pip did quite well when he sold out and retired in about 1987. The garage is still running today, under the new owner’s name.

During his racing career Pip had continued running the family garage in partnership with a school friend. Sales of Esso petrol had proved lucrative, and a Mazda car agency had also been successful, so Pip did quite well when he sold out and retired in about 1987. The garage is still running today, under the new owner’s name.

Before that, though, with no motorcycles to worry about, he’d taken up a completely different hobby and made a concrete-hulled 35 foot ketch-rigged yacht, which he only sailed a couple of times before that hobby was curbed by heart trouble. He believes that the boat is still in existence, and so is his old BMW outfit, whose current owner – Alex McFadzean – loaned it to him for a lap of honour in the Isle of Man during the 1990s. “I hadn’t entirely lost my touch,” he says proudly, “I lapped at 82mph after all that time out of the saddle, so I was quite pleased with myself.”

Pip was equally pleased by an occurrence at the Centenary Celebration for the Dutch TT where he was asked for his autograph by a German fan who declared that he’d been trying to meet him for 30 years. “He said that he’d always been a fan of mine,” beams Pip, “because he regarded me as the Geoff Duke of sidecars. You can’t have a much better testimonial than that, can you?”