There’s much to know about this hard-to-kill bike, including its sheer quality.

Words and photos by Oli Hulme

For years, Steyr-Daimler-Puch A.G of Graz, Austria, made high-quality and innovative split-single two-strokes. But they approached the end of the 1960s with new vigour and a range of conventional yet extremely well-made mopeds, backed up with some sophisticated split single two-strokes.

Early in the 1960s the company had secured a deal with mail order giant Sears, Roebuck & Co to sell its bikes under its Allstate brand. You could order an Allstate-Puch badged as the Twingle from a catalogue, and within days a truck would arrive at your door with a bike in a wooden crate. These mail order motorcycles were almost ready for the road; despite their mechanical sophistication, just a few hours of preparation would see proud new owners heading for the road. In 1965, Sears dropped the Allstate branding and put Sears badges on petrol tanks. The frugal Austrian lightweights were popular among college students looking for cheap transport, rather than long-established motorcyclists.

When the first of the new Puch mopeds arrived in 1965, they had an immediate impact in Europe and the US. They were cheap, easy to look after, and of far higher quality than their rivals. The little mopeds were popular in the UK too, despite being quite a bit more expensive than British rivals like the Raleigh Runabout and Japanese tiddlers thanks to their excellent build quality. In 1966, Puch launched a replacement for its by now antiquated split-singles. This was a conventional 125cc two-stroke, the M125. The bike was partly born from a request from Sears for a cheaper and less complex machine to the split single to cater to a growing market for cheap wheels. Puch took the engine from a very successful trials competition machine it was fielding in Europe to create the M125, which was manufactured between 1966 and 1971.

The new tiddler was marketed in North America as the Sears Lightweight Motorcycle (SR125). This had Sears tank badges and ‘Sears’ written across the back of the seat and had the same specification as Puch-badged European models.

The Puch had a competitive price at £179, slightly more than it’s much cruder and older-spec British rival, the 175cc BSA Bantam. The 50cc capacity difference was a problem in the UK marketplace; while the Puch punched above its weight, being a 125cc single putting out 12bhp, the same as the B175 BSA Bantam, buyer perception was that it was a ‘small’ bike, even though it was physically large – much larger than Japanese or Italian rivals. Buyers being buyers were less likely to pay more for 50cc less, even though the Puch was better made and better equipped. The feeling that the Puch wasn’t big enough was hugely unfair. It was better equipped than most of its rivals, larger than many, had considerable poke, and a lot of charm. The cubic capacity caused a little extra expense for buyers. The insurance group on the popular and ubiquitous Rider Policy meant you paid the same premium if your bike was a 100cc or a 225cc machine. The financial benefit of using a 125 was lower fuel consumption, though at 80-90mpg it was no better than most other 125s.

There were two issues with the Puch that marked it as being a little behind the times. One was that on the early models there was no battery on the M125 basic model, which meant it could not have indicators and the lights only worked when the engine was running; they were powered by a power-generating coil fitted into the magneto. Lights were brighter the faster you went but were disappointingly dim at low revs. There was no ignition switch, with security provided only by an awkwardly positioned steering lock. A Sports or De-Luxe version arrived later, having a slightly racier appearance with chrome tank panels. This was fitted with battery lighting but was otherwise mechanically identical and produced between 1969 and 1971. This was designated the M125S (for Sport) in the UK. Because the slightly more sophisticated and more expensive M125S had a battery, it could have better lights and could be fitted with bar end indicators.

Owners had found that the basic M125 could have its wiring system modified, fairly simply, to fit a battery. In order to ensure the brake light worked, a coil was included in the magneto to provide a constant current to this bulb. By connecting wires to this circuit, enough electricity was provided to give a battery just enough charge to keep it alive, which was very useful when travelling at night or in bad weather. While the lack of a battery meant starting could be challenging on occasion, the magneto/generator ignition also meant you could leave the Puch parked up for months and it would still start, whether the battery was charged or not.

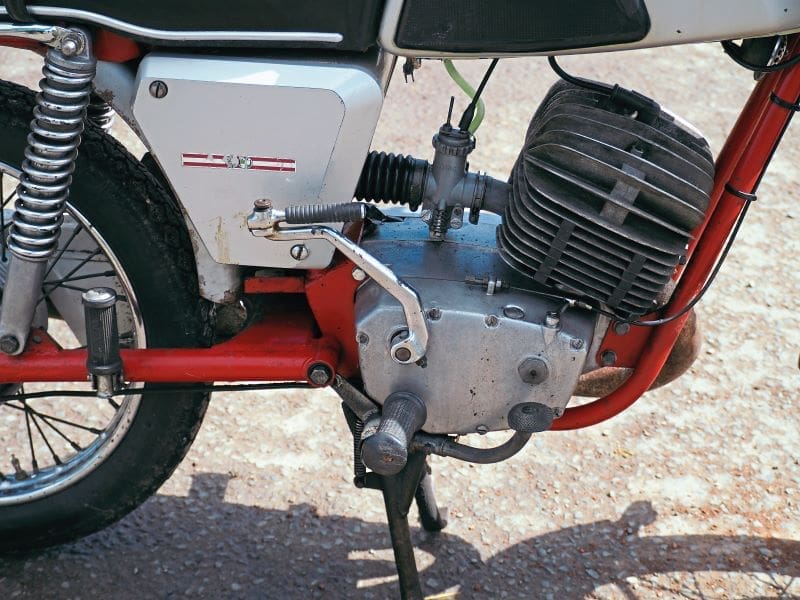

The other outdated feature was that it operated on a ‘petroil’ mix of petrol and two-stroke oil, unlike Japanese rivals which had oil injection – less messy and didn’t need any maths to get the ratio correct. This was an odd decision by Puch, which had pioneered oil injection on the Twingle. Puch, as did other manufacturers, put a handy cup under the petrol cap to make sure you got the oil-petrol ratio correct. You still had to carry around bottles of oil, though. The engine was a simple piston-ported two-stroke single, which had chrome bores. This offered considerable longevity, but if they did wear out, it meant getting the barrel sleeved. Today you can still find new-old-stock engines in Germany for about £1000. The kick-start is a splendid bit of design, allowing a decent throw without fouling the footrests but remaining compact and tucked away, and the clutch is mounted on the right-hand end of the crankshaft. The transmission had four well-spaced gears.

Something that made the Puch stand out was the quality of the original equipment, apart from the European-style ‘snuff box’ switchgear, which, while better than Wipac yet not as good as Japanese offerings, was still pretty good for a 1960s Euro tiddler. Otherwise, there was a host of top-notch kit on there.

The brakes were full-width and excellent, and there was a VDO speedometer in the CEV headlight. There was a CEV taillight, also used on much bigger Ducatis and Moto Guzzis, among others, and ignition by Bosch. The silencer is a Silentium with curious ‘gills’ cut into the rear for some reason, possibly to give better dispersal of blue smoke. The engine castings are of competition standard, and there is lots of heavy finning on the barrel and a very attractive race-inspired, heat-dispersing, radially finned cylinder head. It made the Puch engine appear to be a much bigger capacity than it really was and ensured proper cooling, making the Austrian marvel far less prone to seizing than lesser models. The cradle frame is properly stiff and painted a striking shade of red. The incredibly comfortable seat is from German seat maker Denfeld, which had a long history of making solid rubber seats for BMW and Zundapp and provided top-quality perches for Vespa too, among others. Denfeld also provided much of the other rubber wear.

The whole bike felt grown-up. The airbox was a chunk of cast aluminium and the carb was a Bing with an automatic choke. You pushed down the choke button, started the bike, left it a moment to warm up, and when you rolled back the throttle it turned itself off. On later models, the suspension at the rear was adjustable not by fiddling with the shock, but by fixing the bottom mount in one of three holes on the swingarm mounting plate, depending on the load to be carried. A tuned version of the engine was also used in the original Dalesman motorcycles built in Otley, West Yorkshire, and by Wassell when it made off-roaders, and a company called EFS made versions of the M125 in Portugal.

Austria and back in a weekend

In 1968, Motorcycle Mechanics decided to put the Puch to the test in a big way. It would send a team of four to ride a Puch 125 flat-out from London to Graz in Austria and back again in a long weekend: 2000 miles across Europe and over the Alps and back, sometimes two-up. One Friday morning, the bike was flown to Rotterdam and the team rode the little beast for 23 hours, almost non-stop, getting lost once, averaging 46mph and 75mpg. The only thing that broke was a rear bulb filament. At Graz, the riders had a day off, Puch gave the bike a once over, weakened the mixture, and on the Monday the team rode it back again. It took 19 hours, including changing a fouled spark plug in Munich. Not bad for a 1960s 125, really. As the magazine headlined its test – ‘We tried to break it but couldn’t.’

The Maxi pushes out the M125

Why did the M125, and in particular the M125S, go out of production if it was so good? It was something that had happened in 1969… the launch of the Puch Maxi moped.

The Maxi was simple and cheap, incredibly reliable, safe, and easy to use. Demand rapidly outstripped supply at the Puch factory, and, ever the pragmatist, Puch shut down the M125 production line and put the factory on to building the Maxi. Eventually, the firm had made 1.8 million Maxis, and while later in the 1970s it came up with some of the best-ever sports mopeds, including the Grand Prix and the M50 (the moped that eventually took over the role of the Bantam for Post Office telegram boys), the Maxi was the money-maker.

The M125 was the Austrian company’s last ‘proper motorcycle’, but it definitely went out on a high.

Andy and Poppy – so good he bought it twice

Andy Williams first came across Poppy, the name he has given to his Puch M125, in 2014.

“It had been around a bit,” he said, “and was first registered in Swindon, went to Bristol, then off to Dundee in Scotland and another Scottish owner in a town called Errol, and then it came back to Bristol, where I bought it from a bloke who had done some work for a motor trader who had it for years and gave it to him as payment. He wanted £199 for it but wouldn’t give me the original numberplate, so I suppose he must have sold the number, and I had to reregister it.”

He carried out the battery charging conversion after seeing an article printed in a 2007 edition of Classic Bike Guide by Tony Phelps and fitted the bar end indicators. Following a period of ownership, Andy parted company with the little Puch and three Puch mopeds in his possession after a bout of illness meant he couldn’t ride for a bit. But he kept fettling bikes, concentrating on tuning Honda CB500 twin race bikes.

Early this year, he was on a Facebook page called Great Fun On Small Bikes and spotted Poppy being used in Essex, so he contacted the owner and asked if he wanted the Poppy numberplate to go with it. In response, the owner asked Andy if he wanted the bike to go with the numberplate, so a deal was done and the little Austrian marvel made its way back to Worcestershire, where he rides it through the Malvern hills – and rides it hard.

Andy now runs the Puch-125.org website for fans of the single. “It feels like bikes used to,” he said. “The wide tyres they use on little bikes today have changed the feel of them completely. If you look at old Yamaha 350s or small Triumphs, you could ride them on the footpegs, and the Puch is just like that.

“The front end feels so planted, even though it’s quite soft. And it feels restless but nice with it, especially now I’ve rebalanced the wheels. The bike feels like it’s encouraging you to go faster. Getting 65 out of it is not a problem, and it doesn’t feel like you are riding it too hard at that speed.”

“It’s one of the most pleasant small bikes I’ve ridden,” he added. “As far as grins per mile go, it’s way up there.”

Specification:

ENGINE: 124cc single-cylinder two-stroke BORE/STROKE: 55mm x 52mm COMPRESSION RATIO: 10:1 POWER: 12bhp @ 7000rpm IGNITION: 6v Bosch flywheel magneto ignition TRANSMISSION: Four-speed SUSPENSION: Telescopic front fork, twin shock rear BRAKES: 6.3-inch SLS front and rear TYRES: Front 2.50 x 17, rear: 3.0 x 17 WHEELBASE: 49.5 inches SEAT HEIGHT: 31 inches WEIGHT: 218 lb (wet) FUEL CONSUMPTION: 74mpg TOP SPEED: 70mph