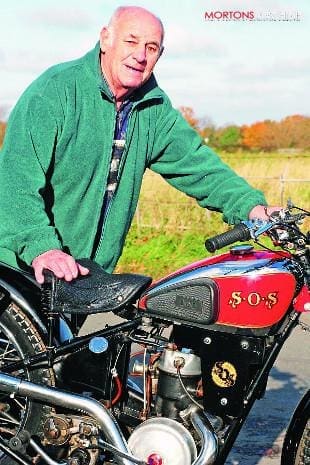

SOS surely has the most pleasing symmetry of all the motorcycle makers who ever traded under a set of initials. The letters changed their meaning during the commercial life of the trademark, although their shapeliness remained encapsulated in the monogram of a rotating wheel right through to the final models. The SOS manufacturing history is relatively short and began in the village of Hallow, in rural Worcestershire, where Leonard Taylor has lived since he was six-years-old. Having moved to the picturesque location with his parents in 1938, he missed seeing motorcycles manufactured in the village centre by only six years. However, he does have some unique memories from a much later era of the bikes’ progenitor, centenarian motorcyclist Len Vale-Onslow, who lived nearby.

“I used to call him ‘Mister’, which was his familiar name, and would occasionally chat with him down in the village,” he recalls. By this time, Leonard already had a particular interest in motorcycling that he shared with his namesake, having bought an SOS motorcycle to restore during the late 1980s. He had long wanted to own an example for its local connections and eventually found one, advertised by a private seller near Heathrow Airport.

“The bike was in a very rough state, with no exhaust pipes or radiator and everything else painted green,” he remembers. “The chap didn’t know quite what he’d got, but I still paid £1200 for it, which reflected its rarity even 20 years ago.”

Leonard took three years to restore the incomplete machine to its original specification. He was fortunate to be able to borrow several standard parts from Vale-Onslow himself, who remained active at the family’s retail shop in Sparkbrook, Birmingham. These components became the patterns for missing items, Leonard using contacts from his employment as a motor mechanic to get the work done locally. The late Reg Kelly provided a piston and barrel from his personal collection of spare parts, covering every SOS model and including several complete machines, which proved to be a handy reference source during the restoration. Nevertheless, after completing the final task of painting the re-chromed fuel tank in the correct shade of red and applying its gold pinstriping by hand, Leonard found that the bike attracted little specific local interest. Clearly, many people living in the village during this time were unaware of the motorcycling heritage that had once put Hallow on the map.

Leonard took three years to restore the incomplete machine to its original specification. He was fortunate to be able to borrow several standard parts from Vale-Onslow himself, who remained active at the family’s retail shop in Sparkbrook, Birmingham. These components became the patterns for missing items, Leonard using contacts from his employment as a motor mechanic to get the work done locally. The late Reg Kelly provided a piston and barrel from his personal collection of spare parts, covering every SOS model and including several complete machines, which proved to be a handy reference source during the restoration. Nevertheless, after completing the final task of painting the re-chromed fuel tank in the correct shade of red and applying its gold pinstriping by hand, Leonard found that the bike attracted little specific local interest. Clearly, many people living in the village during this time were unaware of the motorcycling heritage that had once put Hallow on the map.

“An attractive model having as its chief characteristics economy and comfort, coupled with speed and reliability” was how The Motor Cycle heralded the first production Super Onslow Special, in its issue dated 8 September 1927. In typical style, proprietor Len Vale-Onslow put it more prosaically, announcing “a sound job, a square deal and value for money.”

LH Vale-Onslow’s life story would fill a book by itself. The eighth of nine children, Len first rode a motorcycle built by his brothers on the public road at the age of eight and soon learned to modify various makes of motorcycle, eventually building a complete rolling chassis to his own design. Success in racing from 1923 prompted a demand from local riders for replica machinery, and this led him to set aside a development area in the motor garage that he ran with his brother Cecil in Hallow. The rural premises lacked a mains gas supply for brazing work, so he fabricated frames by a new process of oxy-acetylene welding, having first obtained permission from the Air Ministry to use special chrome-molybdenum tubular steel. No castings were used in a method that ensured both strength and lightness (each duplex full-cradle frame weighed just 19lb), and which ultimately became the industry standard for chassis construction. The first production bikes, assembled from 1926 onwards, used four-stroke JAP and Rudge Python engines and two-stroke Villiers units in various sizes from 172cc up to 343cc, before standardising on Villiers after 1930.

LH Vale-Onslow’s life story would fill a book by itself. The eighth of nine children, Len first rode a motorcycle built by his brothers on the public road at the age of eight and soon learned to modify various makes of motorcycle, eventually building a complete rolling chassis to his own design. Success in racing from 1923 prompted a demand from local riders for replica machinery, and this led him to set aside a development area in the motor garage that he ran with his brother Cecil in Hallow. The rural premises lacked a mains gas supply for brazing work, so he fabricated frames by a new process of oxy-acetylene welding, having first obtained permission from the Air Ministry to use special chrome-molybdenum tubular steel. No castings were used in a method that ensured both strength and lightness (each duplex full-cradle frame weighed just 19lb), and which ultimately became the industry standard for chassis construction. The first production bikes, assembled from 1926 onwards, used four-stroke JAP and Rudge Python engines and two-stroke Villiers units in various sizes from 172cc up to 343cc, before standardising on Villiers after 1930.

When the range expanded to meet further demand, Len moved production to larger factory premises, still in Hallow, where up to 25 machines were completed to a luxury specification each week. By this time, his competition record on SOS machinery had inspired a catchy sales slogan of ‘Success On Success’ and he shared with George Brough the rare distinction of being a racer who designed and manufactured his own mounts. Problems in the supply chain led him to relocate production to Birmingham early in 1932 and it was around this time that he completed the design of a water-cooled cylinder head and barrel conversion for air-cooled Villiers engines. Sight of the running prototype prompted the Wolverhampton-based company to take up the idea itself, assigning one year’s exclusive supply of the new units to the SOS assembly line. But Len had already realised that greater long-term profitability lay in retailing, so he sold the manufacturing rights in October 1933, just three months after a water-cooled 249cc model joined the range.

Leonard Taylor’s 1936 model DW demonstrates the inherent simplicity of the water-cooled top end design on the Mark XIVA Villiers engine, with two large-bore rubber hoses leading from the cylinder block and head to a radiator housed in a steel cowling beneath the fuel tank. Just three bolts secure the cylinder head and this, unusually for a two-stroke, incorporates a decompression valve that is operated by a lever on the left handlebar. After flooding the gauze-filtered Villiers carburettor, the low-compression motor proves easy to start and ticks over with a fair degree of noise, the nearside upswept exhaust pipe doing a useful job of shielding the rider’s left boot from the rotating flywheel and exposed rear section of the primary drive.

Leonard Taylor’s 1936 model DW demonstrates the inherent simplicity of the water-cooled top end design on the Mark XIVA Villiers engine, with two large-bore rubber hoses leading from the cylinder block and head to a radiator housed in a steel cowling beneath the fuel tank. Just three bolts secure the cylinder head and this, unusually for a two-stroke, incorporates a decompression valve that is operated by a lever on the left handlebar. After flooding the gauze-filtered Villiers carburettor, the low-compression motor proves easy to start and ticks over with a fair degree of noise, the nearside upswept exhaust pipe doing a useful job of shielding the rider’s left boot from the rotating flywheel and exposed rear section of the primary drive.

After weakening the fuel supply with the inscribed mixture control on the right handlebar, I click the foot lever down for first gear and set off to ride through the village of Hallow. The engine emits plenty of oily smoke during the first couple of miles, from twin high-level silencers that were a feature from the earliest SOS designs. The three-speed Albion gearbox feels positive and its ratios seem well spaced for normal road work as I gradually increase the pace, the blue cloud behind me dissipating once the engine has fully warmed up. There is adequate torque for most solo situations, but the long-stroke engine would surely have laboured to pull top gear uphill, especially with a passenger in the lightweight single-seat sidecar that was an optional extra. A sidecar mounting lug is visible beneath the seat pivot on the nearside and the frame is well braced, particularly in its lower sections. To the rear of the lug is a chromed tap for regulating oil flow from a separate tank as part of the Villiers Automatic Lubrication System, though Leonard prefers to pre-mix two-stroke oil with the petrol by the traditional method of a measuring jug and a good shake, which probably accounts for the initial exhaust haze.

Good brakes more than compensate for a lack of engine retardation, although the rear is quite fierce and difficult to apply progressively, due to a steep-set pedal that really needs remounting in its proper position. Webb girder forks absorb most surface irregularities, a plush sprung saddle dealing with any large bumps that get through. My knees project some way beyond the rubber tank grips in spite of rearward-set footrests, though the bike’s compact dimensions would no doubt have suited Len Vale-Onslow’s limited stature perfectly. Overall, the machine has an air of well-engineered quality in spite of its small size, limited horsepower rating and significant mechanical noise.

Good brakes more than compensate for a lack of engine retardation, although the rear is quite fierce and difficult to apply progressively, due to a steep-set pedal that really needs remounting in its proper position. Webb girder forks absorb most surface irregularities, a plush sprung saddle dealing with any large bumps that get through. My knees project some way beyond the rubber tank grips in spite of rearward-set footrests, though the bike’s compact dimensions would no doubt have suited Len Vale-Onslow’s limited stature perfectly. Overall, the machine has an air of well-engineered quality in spite of its small size, limited horsepower rating and significant mechanical noise.

If a lightweight, luxury two-stroke roadster is not a contradiction in terms, then this is the best example of its period that I have sampled on the road.

I ride past the apartment block where ‘Mister’ spent the last five years of his life. A little further along, I pass the site of the black-and-white Hallow Garage, next to the Royal Oak pub, where he assembled the very first SOS models. This is now a nondescript brick-built storage shed with planning permission for a four-bedroom house. The factory building still stands across the road, though it houses a modern car dealership. A year or so after the move to Birmingham, the SOS business was sold to TG ‘Tommy’ Meeten, an established Surrey agent, who strove to maintain its reputation as the premier manufacturer of Villiers-engined lightweights. Accordingly, he rebranded the 1934 SOS range as ‘So Obviously Superior’, advertising its liquid-cooled models as ‘mile a minute two-strokes’. This accolade derived from the water jacket overcoming the Villiers’ inherent tendency to seize up if ridden hard for long periods without a break, though it did add complexity to engine servicing and looked ungainly compared to the air-cooled motors.

Tommy Meeten was a successful all-round racer and ardent fan of two-strokes, who had been instrumental in founding the British Two-Stroke Club in 1929. He developed new sporting and luxury models for the SOS range, making tuning and chassis options available in-house, but failed to secure a military contract and so stopped production in 1939. Plans to restart manufacture after the war were foiled by theft of equipment from the factory, though Meeten continued to service the bikes and sold other Villiers-powered makes from his Meeten’s Motor Mecca shop up to the mid-1960s.

Tommy Meeten was a successful all-round racer and ardent fan of two-strokes, who had been instrumental in founding the British Two-Stroke Club in 1929. He developed new sporting and luxury models for the SOS range, making tuning and chassis options available in-house, but failed to secure a military contract and so stopped production in 1939. Plans to restart manufacture after the war were foiled by theft of equipment from the factory, though Meeten continued to service the bikes and sold other Villiers-powered makes from his Meeten’s Motor Mecca shop up to the mid-1960s.

The letters SOS in Morse code became the worldwide standard for a maritime radio distress signal on 1 July 1908 and remained so for the next 91 years. Incredibly, Len Vale-Onslow both predated and outlived this famous cipher, winning more than 400 trophies on his way to becoming the world’s oldest and longest-active rider, and ultimately garnering plaudits that included an MBE, honorary degree and lifetime achievement award for his services to motorcycling. His family’s retail shop still exists on its original site on the Stratford Road in Birmingham and many of the SOS models that Len designed and built still run today, making him a pioneer in every sense.

Leonard Taylor believes that the younger inhabitants of Hallow only became aware of the celebrity in their midst when ‘Mister’ celebrated his100th birthday by riding one of his self-restored machines along Pall Mall in London, for the benefit of cameras.

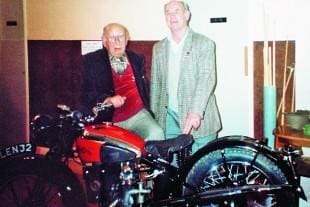

Subsequently, Len’s daughter Jean, who still lives locally, asked if she could borrow Leonard’s SOS for her father’s 103rd birthday party in May 2003. Leonard remembers the occasion well, “I have a photograph of him sat on my bike during that special day, less than a year before he died on St George’s Day in 2004.” Now aged 76, he feels it is appropriate that fate should have brought together man and machine for that ultimate reunion in Hallow. “I feel that my SOS has still got some of Len’s soul in it and I tip my hat to him every time I fire it up,” he says.