Then imagine how you would have felt when somebody asked you for a ride, on a busy morning, in the traffic. Rehearse your reply.

David Nairne Clark coped like a man, though a source close to the family leaked the information that, in the subsequent 15 minutes, he wore a track into the lawn between the front door and the hedge, and started . smoking again. He denies this.

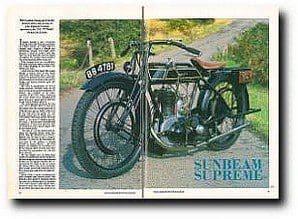

BB 4781 is exceptional. As well as being perfectly restored, most of the parts of this Sporting Solo Sunbeam (TT Model) are common to no other machine in the 1921 range. Replacing the items which were damaged took years and cost a great deal in cash and swaps. Was it worth it? Read on.

The Sporting Solo Sunbeam for that year was a genuine flyer. It had been developed from the racing machines of 1920 like the one on which Tommy de la Hay had won the Senior 7f. His average speed was 51.79mph over the 226.5 miles, a new race record. The road model — the term IT Replica was not yet in use — had the racer’s minimal road equipment, a close-ratio gearbox with no kickstarter, and a tuned engine with an aluminium piston.

“We take it,” say the instructions for using the Sporting Model 3.5hp Sunbeam, “that the owner is not a novice.” Indeed not, for this is not a novice’s machine. To own it at all would have set you back by 145 guineas — around £6,000 in today’s money — for what might, not unkindly, be described as a motor bicycle. Most of those sold were intended for competition use, and few have survived.

“We take it,” say the instructions for using the Sporting Model 3.5hp Sunbeam, “that the owner is not a novice.” Indeed not, for this is not a novice’s machine. To own it at all would have set you back by 145 guineas — around £6,000 in today’s money — for what might, not unkindly, be described as a motor bicycle. Most of those sold were intended for competition use, and few have survived.

BB was bought new by baker John Palmer of Coldstream, not for racing but for fast transport, both solo and with Mrs Palmer on the flapper bracket. She remembered the ‘beam as able to outrun the fastest bikes in the area Eventually, time caught up with the Sunbeam and it was stored away and, over the years, forgotten.

David Clark, a native of Coldstream and a former army motor cyclist, had rebuilt a fine Model 9 Sunbeam which he took on a holiday back to Scotland. “Oh,” said a friend. “John Palmer had a Sunbeam some time since.” David went to see John who said that, as far as he knew, the bike was still in the shed and that David could have it if he could find any use for it. Sadly, time had caught up with the shed as well. The collapse of the stove chimney had left water dripping on to the bike and soaking the floor. The ends of both stands and the front rim had rotted away.

Petrol tank

Worse was the effect of the drip itself, which had cut through the top tube of the frame, worn a huge hole in the petrol tank and eaten away the top of the iron cylinder, exposing the piston, before wrecking the primary chaincase.

It had almost cut the bike in two. “The front and back mudguards,” says David dryly, “were in quite good condition.” A thorough search of the shed revealed some minor parts, including an AMAC float chamber top which John had discarded in favour of the Amal one still on the bike — AMAC tops have no fixing screw and tend to fall off — and the rear oilbath, taken off years before, squashed flat under a family Bible.

Home to the Black Country came the remains. Running alongside other Sunbeam rebuilds — for David loves no other make — the work was started by carefully jigging the damaged frame and having a top tube made and inserted by another Clarke, Jim, the wizard welder of Walsall. The apprentices at Marston Palmer Ltd, the successors to John Marston, made a new tank to the original dimensions, using the existing brass fittings. “Not a pattern tank,” says David, “but a replacement from the factory.”

Home to the Black Country came the remains. Running alongside other Sunbeam rebuilds — for David loves no other make — the work was started by carefully jigging the damaged frame and having a top tube made and inserted by another Clarke, Jim, the wizard welder of Walsall. The apprentices at Marston Palmer Ltd, the successors to John Marston, made a new tank to the original dimensions, using the existing brass fittings. “Not a pattern tank,” says David, “but a replacement from the factory.”

A cylinder was prised out of the hands of a fellow enthusiast, though David regretted the number of original Sunbeam publications he had to part with in exchange. Why? Because the 85mm fixed-head cylinder was promptly ruined by a `skilled’ reborer and another — more rare than rare — had to be dragged from the same grasping collector. The man also released a good front chaincase, unique to this model, in exchange for the rest of David’s library. David bored the second cylinder himself.

As the build continued, David took care to ensure that only genuine parts were used. Wheel spokes, for instance, came from other Sunbeam wheels and were cut down and re-threaded in David’s workshop, a 14ft by 6ft wooden shed. He does all the polishing and plating himself on one of Dynic Sales nickel plating kits.

Eventually, the metalwork was fit for painting, again a job done at home. Many coats and much rubbing down later the finish is as good as that of the Sunbeam factory. The tank was also enamelled at home and then gold-leaf was applied by a local craftsman, David being contemptuous of tank restoration firms who take the cheap way out with gold paint. The transfers were found in a drawer at a local factory and are Sunbeam originals.

Contemplated his ride

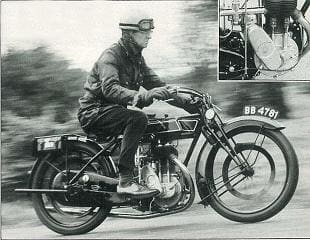

Those are some of the reasons for the nervousness felt by your reporter as he contemplated his ride. This machine isn’t a bolt together kit of pre-finished pattern bits but all Sunbeam, all rebuilt, all by hand.

It’s worth quoting the book on starting: “Inject a few drops of petrol into the cylinder head through the compression tap. A priming cock is provided for this purpose. Ensure that the petrol is flowing by flooding the carburettor. Engage middle gear, close air lever, open gas lever not more than one third, set magneto at half advance (all Sunbeam levers open inwards) raise exhaust valve lifter and push machine forward to set the engine revolving. Directly the engine commences to fire, adjust the carburettor and magneto levers so that it fires regularly and as slowly as possible.” Much more fun than an electric starter.

David sets the controls but starts by giving the rear wheel a tug whilst the bike is on the stand. The result is the traditional Sunbeam tenor boom from the straight-through pipe and no other sound save for a chuffing noise from the AMAC’s trumpet. There is no mechanical noise at all. Once, all Sunbeams sounded like this one, a testimony to David Clark and Horace Banks, his mentor in mechanics.

David sets the controls but starts by giving the rear wheel a tug whilst the bike is on the stand. The result is the traditional Sunbeam tenor boom from the straight-through pipe and no other sound save for a chuffing noise from the AMAC’s trumpet. There is no mechanical noise at all. Once, all Sunbeams sounded like this one, a testimony to David Clark and Horace Banks, his mentor in mechanics.

And the ride? Naturally I have never ridden a new Sunbeam before, the Paul Street factory having closed years before I was born, but this must have been how the new owner felt. Declutch, lever down for first gear, let the clutch in as the throttle lever comes back, glance round and away. Gear lever up for second, a two finger change despite this being the first edition of Sunbeam’s infamous ‘crash’ gearbox, before accelerating gently.

A bit of straight road here, so magneto lever further back and a gentle pootle down the road to warm up, get comfortable on the lovely, leaf-sprung saddle (which took eight years to find) and check the oil drip in the sight feed glass. A high order of computational skill was required of the rider, before automatic oil pumps, since Sunbeams commanded that a pump full of oil should pass through the drip feed about every eight miles. Not easy to judge when no odometer is fitted.

Second gear will cope with most traffic, the machine’s light weight and the engine flexibility ensuring that the speed range is from walking pace, with a touch of air lever and about half advance, up to a putative 50 when pressed. A quick check for the brakes, thankfully changed from the original Sunbeam traditional placing of the front brake on the left, pedal cycle style.

A longish stretch of open road prompts a change into top, the mag lever fully back and a fingerful of throttle. We’re off, like a little rocket. This is no soft, vintage side-valve but a true sportster; so much so that lines of cars seem to go backwards as we whistle past, pull ing a patently illegal speed. (Didn’t I tell you that, David?) In deference to running in we stick to the local bypass. Handling? Very light and direct in the manner of the Twenties. No problem at all.

There has to be a catch, a disadvantage to this beautifully balanced thoroughbred, and of course, it appears as the traffic lights change. The front brake unlikely to cause a skid, said Sunbeam in 1921 — has an almost nil effect on forward motion, and a look at its built-in negative servo design shows why. The back brake is much better, but a fluency with the hand change and lever controls is necessary to use the excellent engine braking when needed.

Quite simply, the Solo is not for riders unskilled in handling the demanding characteristics of a fast vintage motorcycle, riding one of which needs much more skill and concentration than the mere twistgrip and pedal work of post 1950 machines. In good hands, the Sunbeam is supreme.

So there it is. BB 4781 is a true 100 Point rebuild of a rare performance motorcycle which goes every bit as well as it looks. View original article