We would lay money on the fact that the event that virtually all of us have in common, that most of us will have attended at least once, is not the TT or the Dragon Rally, but the International Cycle and Motor Cycle Show. Here John Milton takes a look back to the show of 1967 using Mortons Archive images.

Back in the middle of the 20th century, there was one event to which almost all motorcyclists looked forward with enthusiasm. It brightened the gloom of an oncoming winter, it showed us what was to come, it gave us something to dream about: it was the International Cycle and Motor Cycle Show.

The first major show in this country was the Stanley Cycle Show, held at the Athenaeum in Camden and then the Royal Agricultural Hall in Islington, and always towards the end of the year. (In 1896 Harry Lawson ran a summer show he called the International Motor Exhibition in Kensington, but anyone who has followed the exploits and often scurrilous career of Mr Lawson in the A-Z of British Motorcycles will be unsurprised to hear that was a one-off event.)

Then in 1911 the Stanley Show was replaced by the Olympia Motor Cycle Show which moved the traditional dates by two weeks to the beginning of November; although the show would move around a little, it continued to be somewhere in November. Then, in 1937, the show moved to Olympia’s larger neighbour Earls Court, where it would stay for more than 40 years.

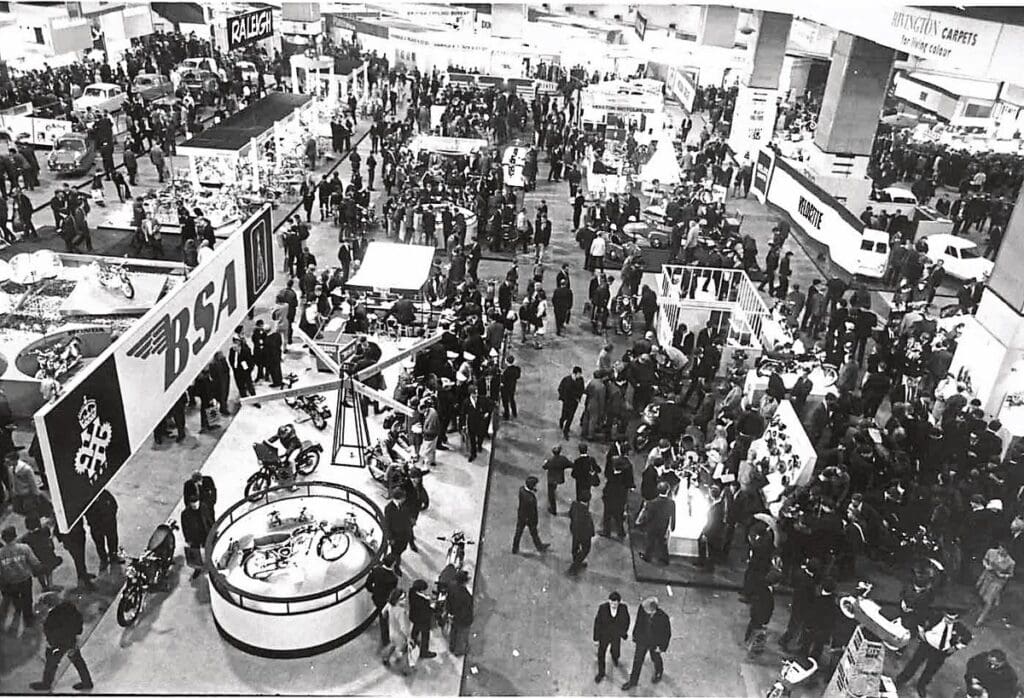

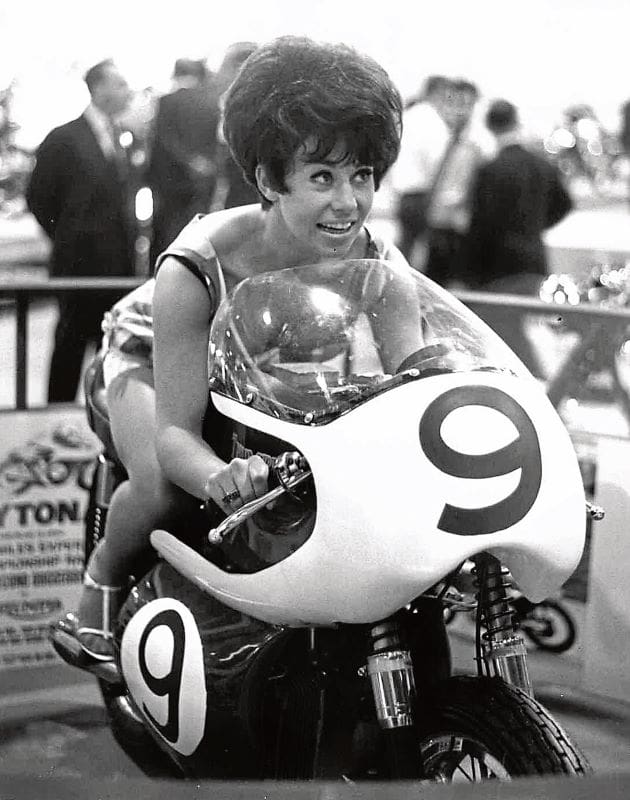

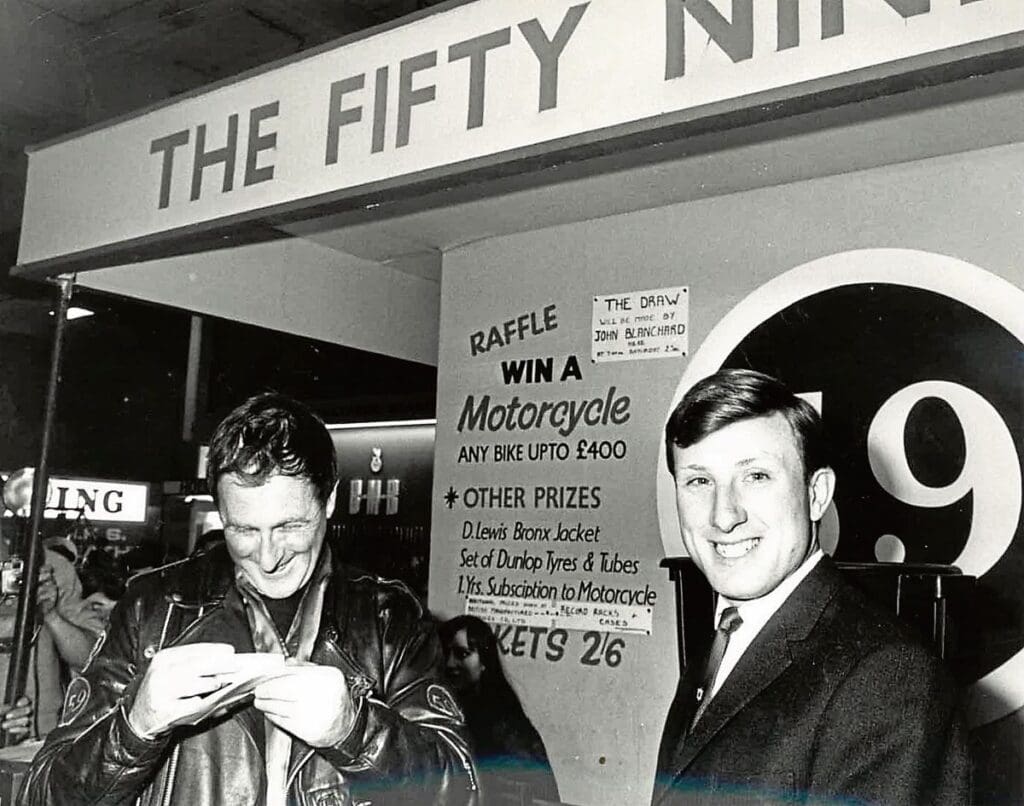

It rapidly became the most important motorcycle show in the world, an event where you could see all the models for the coming year and get a first look at the new machines which made their global debut at Earls Court. Long before Milan and Tokyo and Intermot, before a photo of a new machine could go around the world at the click of a button, there was the International Cycle and Motor Cycle Show. It was a show where you went to look at motorcycles but to which few people would ride their own bikes. For some it was the trepidation of riding in London, for others the horror stories about parking and bike thieves, but most people arrived at Earls Court by train, tube, coach, car or in minibuses. After all, as you will see from our photos of the 1967 show, many showgoers were suited and booted for the occasion, rather than in their bike gear, conscious that by letting the train (or the tube or bus) take the strain they could gather up armfuls of brochures and giveaways, as well as having the odd refreshing shandy (and the opportunity to complain about “them London prices!”).

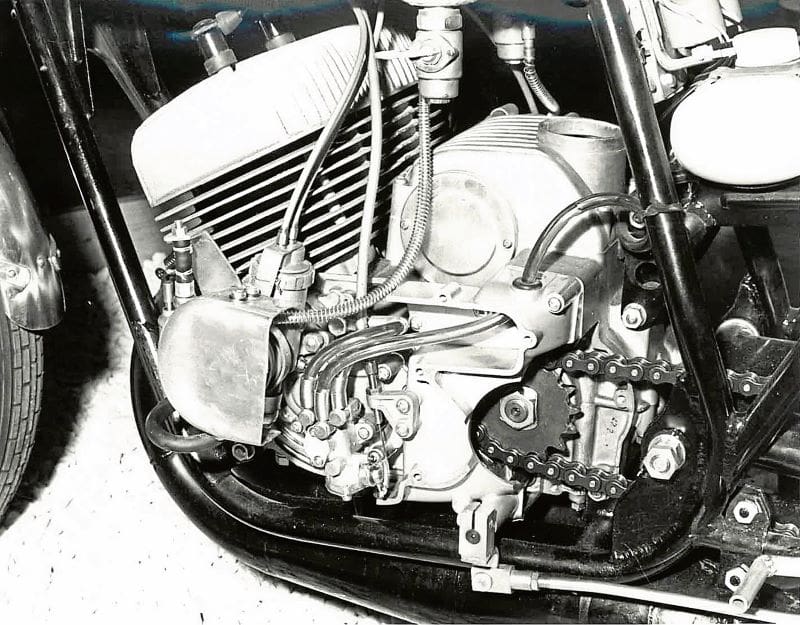

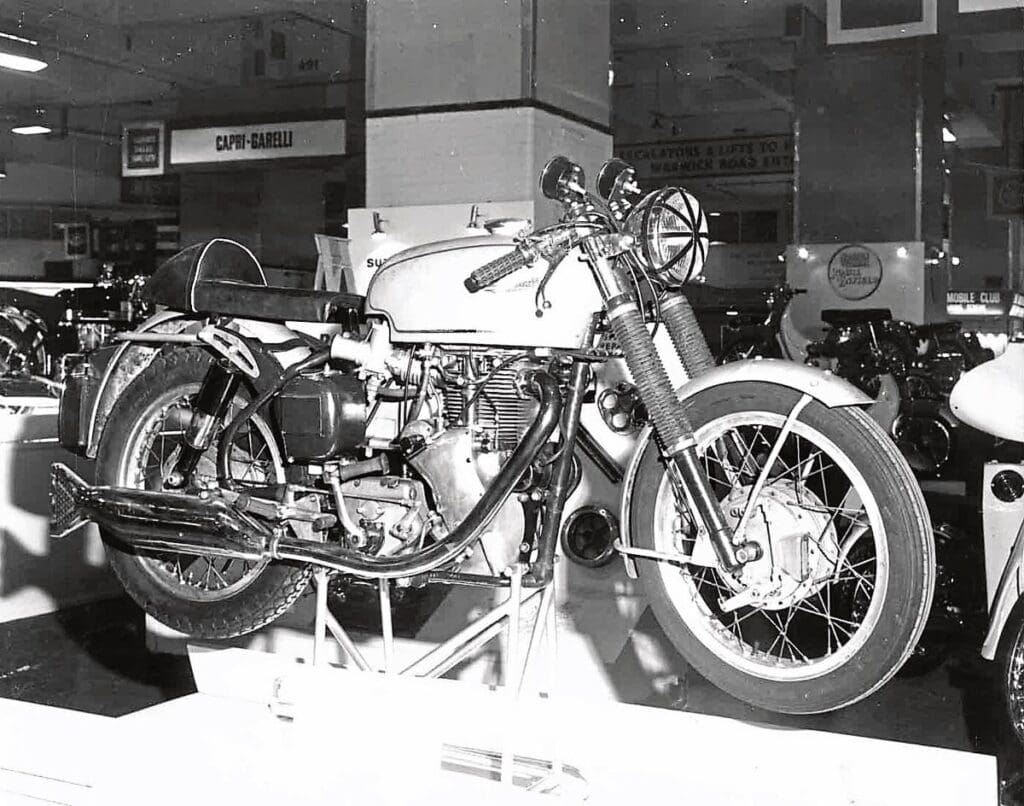

The star of the 1967 show was the new 750cc Norton Commando with its isolastic frame. It was hailed not simply as a new model, but as one which was going to save the British motorcycle industry, which was already starting to see the writing on the wall, as well as provide a large-capacity machine for the American market that Norton-Villiers so desperately needed.

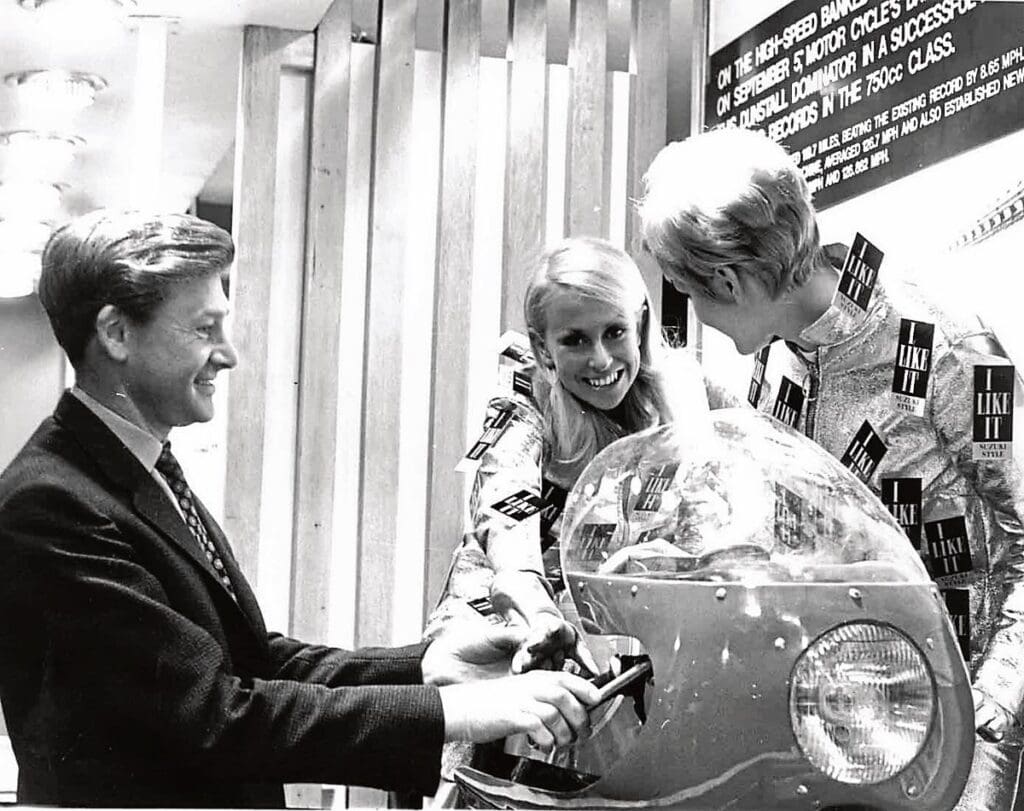

The Commando on display was certainly interesting. Finished in silver, it sported an orange seat and a top speed of more than 200mph, while three conversion kits, produced in conjunction with Paul Dunstall, would be available to provide between 10 and 20% extra power.

Also new was the AJS production racer with a 247cc Starmaker engine and a six-speed gearbox, while Greeves unveiled the Oulton, a big sibling to the successful Silverstone, but destined to become the least well-known of Thundersley’s products. Although its slimmed-down weight should have made it a contender, it couldn’t come close to the success of the Silverstone and just 21 Oultons were built.

In 1968, Bert Greeves retired and Greeves stopped making production racers altogether.

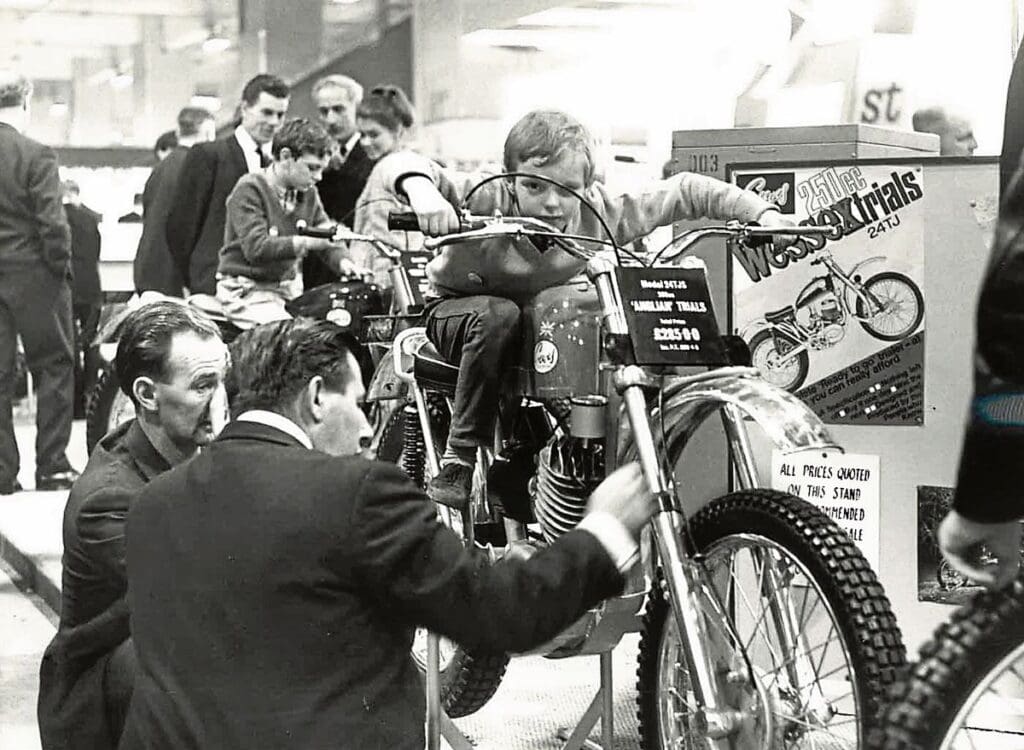

What is noticeable from looking at photos of the 1967 show is how, with the exception of the Commando, there was little new from the main British manufacturers. If people were hoping to see Triumph’s long rumoured three-cylinder machine they would have to wait another year for the Trident and the BSA Rocket 3. Other notable absences were British 50cc machines. Why should this be of concern? Well, it was almost 1968 and there were already rumblings afoot of a change in the law. Although 16-year-olds were still allowed to ride 250cc bikes on L-plates, it was clear that sooner rather than later this would be changed to limit those young people to 50cc machines fitted with pedals until they turned 17. The law would eventually take effect three years later in 1971, but the British motorcycle industry was, at this point, doing little to woo this youthful audience.

Instead, it was left to the Europeans to produce machines that would appeal to these disenfranchised 16-year-olds. One such was the Solifer Super Sport which was designed in Finland but fitted with an Anker M37 49cc single cylinder engine and a claimed top speed of 60mph. Moreover, it looked more like a motorcycle that a lad’s big brother would ride, rather than a pedal moped his mum might own. It was a trend that would be capitalised upon by, most famously, Yamaha with the FS1-E, in 1972. But the only British firm at the 1967 show who seemed to be taking note of this future 50cc market was Heldun Engineering and it would go bust within six months.

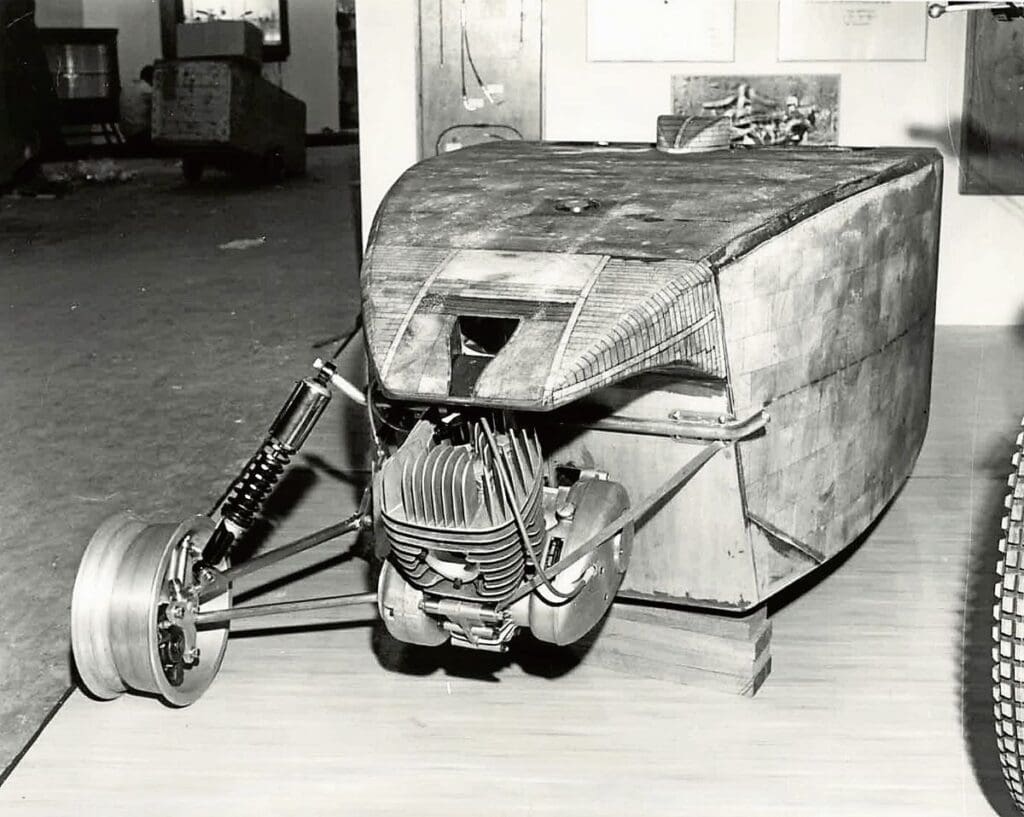

But the 1967 show was, if anything, a tipping point. The Japanese manufacturers, until then something of a novelty at the annual show, were suddenly there in number and with bigger stands than ever before. Honda, Suzuki, Yamaha, Bridgestone and Kawasaki were all present. While Lucas had at the heart of its stand a machine which claimed to represent the future, perhaps a better bellwether of the years to come could be seen by looking at the show as a whole and witnessing the apathy and unwillingness to change of the main British manufacturers and the enthusiasm of the up-and-coming Japanese companies.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing but, from the viewpoint of the 21st century, it could be said that the 1967 International Cycle and Motor Cycle Show was a portent of what was to come.