John Milton looks back on the life of the man they called ‘the first motorcycle superstar’.

This July was the 30th anniversary of the death of Stanley Woods, the man who dominated motorcycle racing in the years before the Second World War. His death saw not only the passing of one of this country’s most successful racers, but of the last link with that glittering era and a man who, in many ways, epitomised those times.

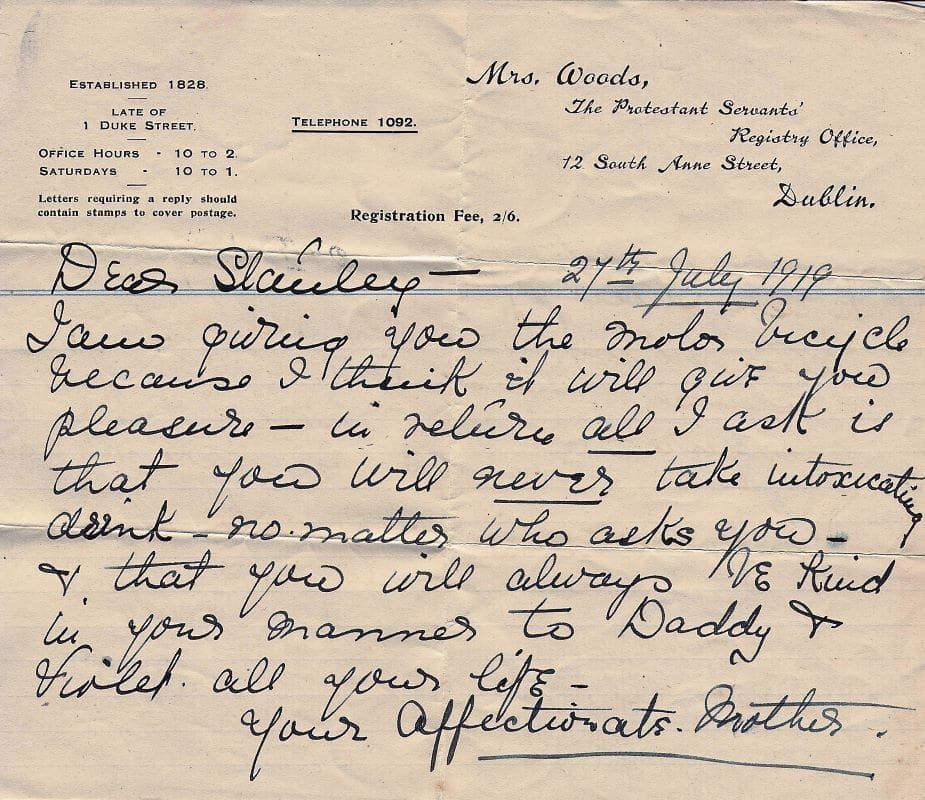

Stanley Woods was born in Dublin in November 1903 and was educated at the High School, Dublin, where fellow motorcycle racer Reg Armstrong would later be a pupil (some decades before Stanley, poet William Butler Yeats had also attended the same school). At the age of 13, Stanley was taught to ride by his next-door neighbour on an Indian and this instilled a love of two wheels which would dictate the course of his life. His father was a salesman for Mackintosh toffee and Stanley persuaded him to purchase a 1000cc Harley-Davidson combination on which Stanley would chauffeur him around to make his calls. There may have been an ulterior motive here for it was this machine that a young Woods borrowed to make his road racing debut in 1921 (much to his surprise, his father agreed to loan him the Harley).

Having removed the sidecar, Stanley took part in the Banbridge 50 although youth, inexperience and enthusiasm resulted in a crash which ended his race and broke a handlebar. However, there was still the dilemma of riding the bike home which the resourceful lad solved by cutting a holly branch out of a hedge and using it to replace the broken ’bar.

It must be presumed that Woods Senior wasn’t too perturbed for Stanley went on to use the Harley in sprints and races and, in 1921, took it to the Isle of Man TT races with his friend CW ‘Paddy’ Johnston who was equally as keen on two wheels and happened to be the Dublin agent for Cotton. (Paddy would himself race at the TT many times and, after a spell as a dispatch rider during the Second World War, was a founder member of the Normandy Motorcycle Club.) That year they were both spectators, but halfway through the race Stanley turned to Paddy and said: “I could do that.” Paddy said he could too – and they did, both returning in 1922 as competitors!

Telling a few fibs

However, there was the problem of what to ride. Back home in Dublin, Stanley wrote to countless manufacturers to request the loan of a machine for the 1922 TT. Those companies which were only going to enter 500cc bikes he assured that he already had a Junior ride and was therefore looking for a machine for the Senior race, while those makers of 350cc motorcycles were told that he had a machine for the Senior TT and was only after a smaller bike for the Junior. Both, of course, were whopping lies!

But Bill Cotton was sufficiently intrigued by the young Irishman’s letter to make further enquiries. It was here that Paddy Johnston stepped in and provided a glowing reference that described Stanley as little short of a racing superstar. (Stanley also provided two other referees, although he later cheerfully admitted that he wrote both letters which described himself as a superb rider!) Bill Cotton not only agreed to lend Stanley a machine for the TT, but also to pay half his entry fee. It was somewhat of a surprise when the boy Woods turned up and was little more than a schoolboy – he was indeed just 18.

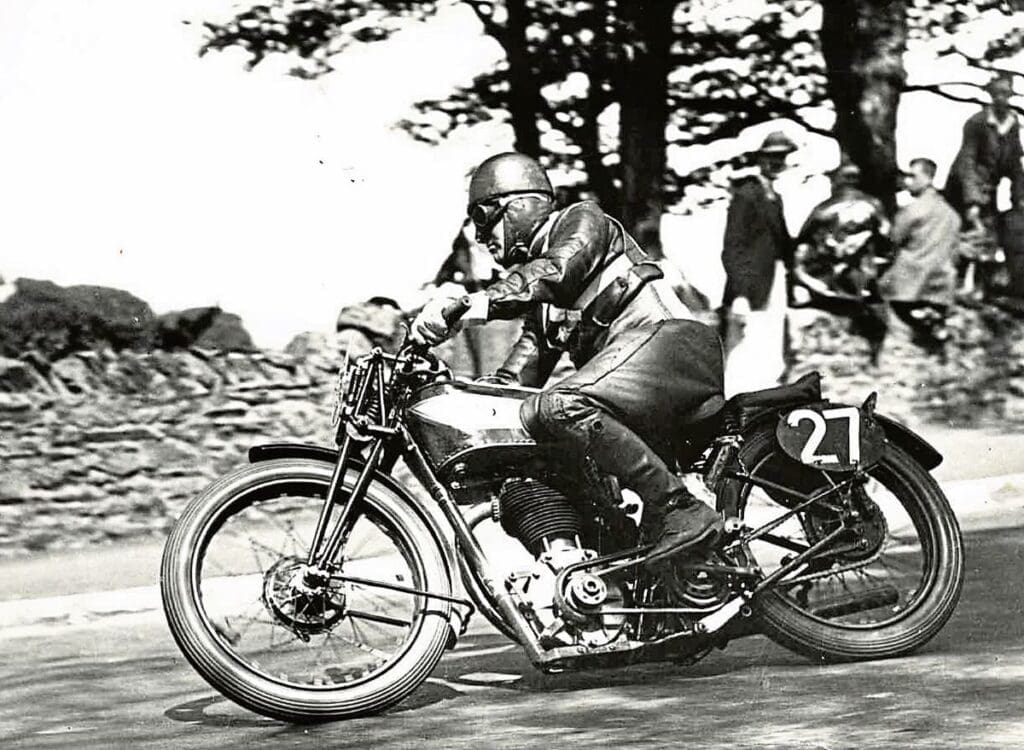

It was quite a gamble for Cotton for 1922 was the first year that the Gloucester firm, then just two years old, was competing in the TT. But if Stanley’s age had been a shock, then the teenager’s racing prowess would be even more of a surprise. It didn’t start promisingly. Spare spark plugs fell out of his pocket on the start line and Stanley stopped to pick them up. He made up time but then fell off on lap two, although not before he’d hit a kerb and broken off an exhaust pipe at the port. Pulling into the pits, the bike – and Stanley – caught fire when fuel splashed on to that hot port. Back out on the track, he had to stop to replace an exhaust valve. Later in the race he discovered that, during the fire, the rear brake cam lever had split and consequently he had no brakes. Then, on the last lap, he fell off again at the Ramsey Hairpin. And modern racers think they have it tough!

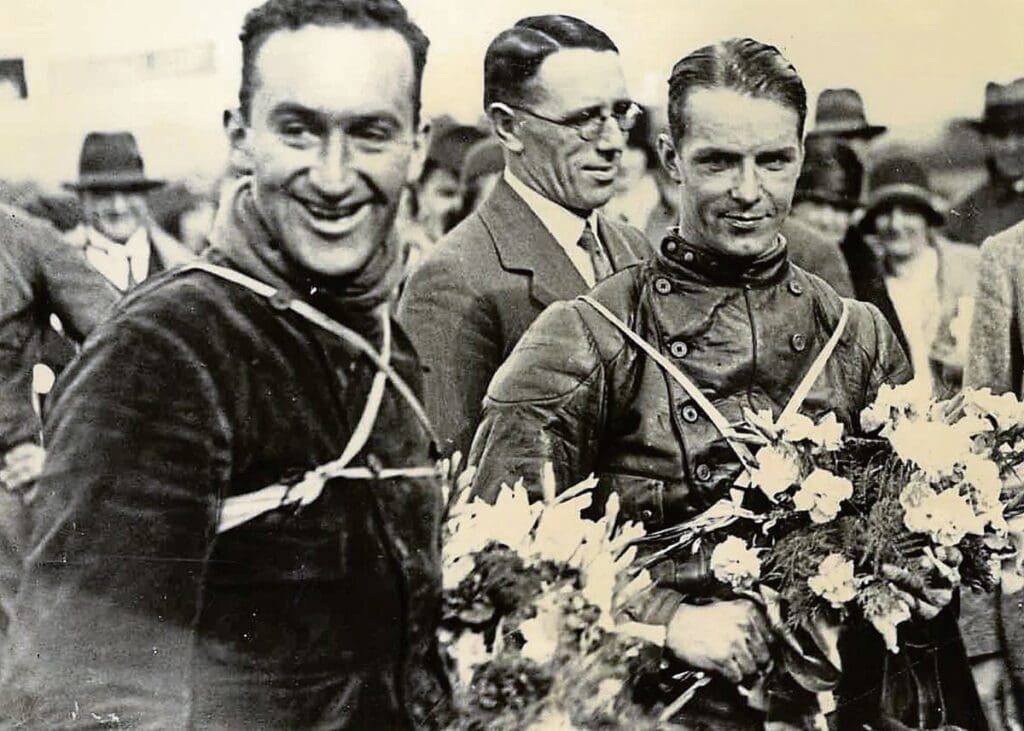

Despite this, Stanley Woods finished the 1922 Junior TT – with no brakes – in fifth place. It was the best result of the three Cottons entered in the race and it assured the youngster of a ride in the 1923 Junior TT. Stanley rewarded Bill Cotton’s faith by winning that race, the first win for Cotton and the first of Stanley Woods’ 10 TT victories. (Incidentally, the same year his friend Paddy Johnston also won the 200-mile race at Brooklands for the Cotton factory.)

The move to Norton

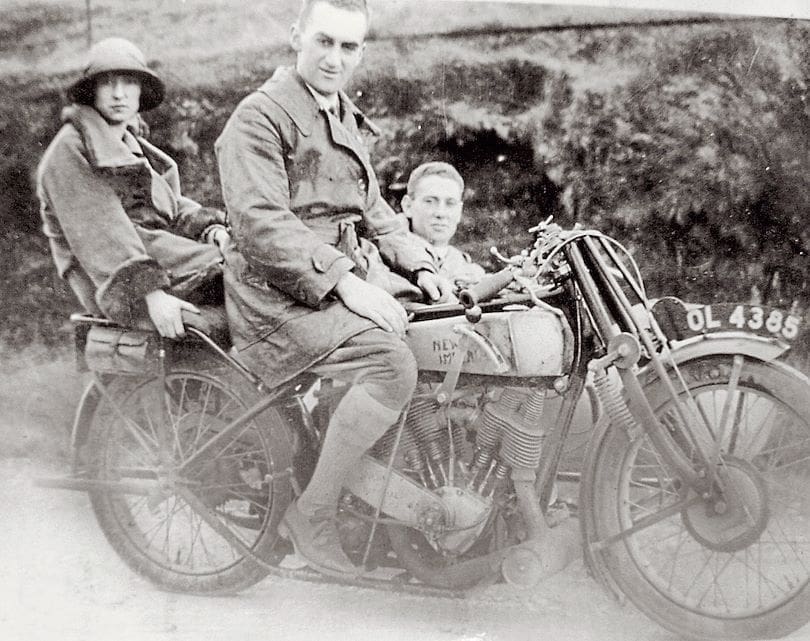

Still just 20 years old but with some money in his pocket from his wins, Stanley decided to buy a new big V-twin which he could use both on the road and for racing. He had set his cap at a Brough Superior SS80 although that came to naught when George Brough refused to give him a discount. Instead he talked New Imperial into selling him a JAP-engined machine at an impressive 40% off! He called the Model 11 Super Sports ‘Patricia’ and had some success in road races in Ireland on it. He was adored by the press for his flair and his gift of the gab, leading to his nickname of ‘The Irish Dasher’.

Ever ambitious, Stanley would soon move on from Cotton who, it appears, he found a little too casual in its approach to racing. He wanted to work with a concern that would further his career and he found that with Norton, although it proved to be a love/hate relationship. However, in 1926, he won the Senior TT for Norton and this allowed him to turn professional the following year; until then he had followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming a commercial traveller for Mackintosh toffee. It was the start of a glittering career; over the next few years he went on to win some 29 Grands Prix (including seven times at the Ulster Grand Prix) with a remarkable 10 TT wins, a record that would stand for more than a quarter of a century. His racing took him all over Europe and, at some point, he secretly married a French woman, Mme Dumonteil, a marriage which didn’t come to light until he divorced her in 1936 to marry a beautiful young Canadian artist, Mildred Ross; they would become sport’s first glamorous celebrity couple.

Leaving Bracebridge St

In 1932 and 1933 Stanley won both the Junior and Senior TT races for Norton, but he was unhappy with the Bracebridge Street factory. There were arguments over team orders and money and in 1934 he moved to Husqvarna, although it was a short-lived arrangement with the Swedish company. By the following year, he was riding for Moto Guzzi and, in 1935, won both the Junior and Senior TT on a Guzzi, only the second time that a non-British bike had won the TT, and the first since 1911 when an Indian had been victorious. In the 500cc race there was a sweet moment when he passed Jimmy Guthrie to snatch victory – Guthrie was the new team leader for Norton. Incidentally, Stanley was an eyewitness to the crash in the 1937 German Grand Prix which killed Guthrie and he always claimed that DKW rider Kurt Mansfield forced Jimmy off the track, despite being a lap behind. It was Stanley’s belief that the move was deliberate because the Nazi regime was angered by the success of the English riders.

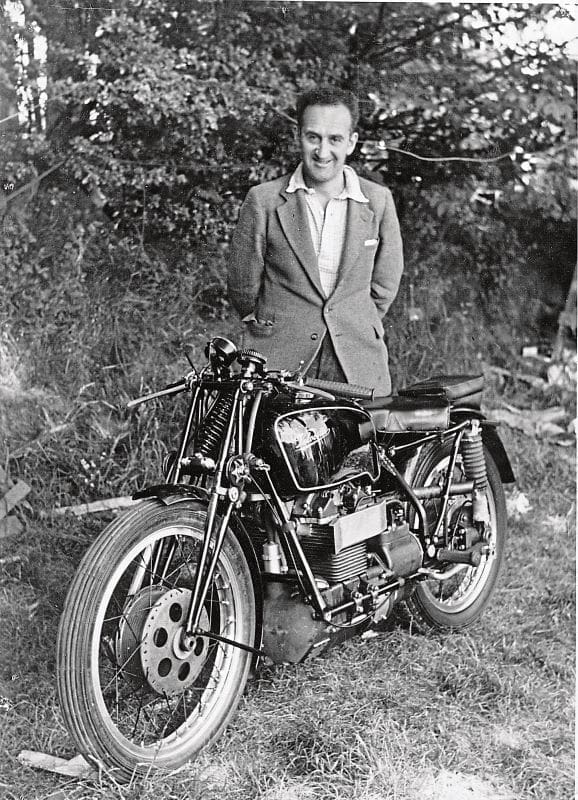

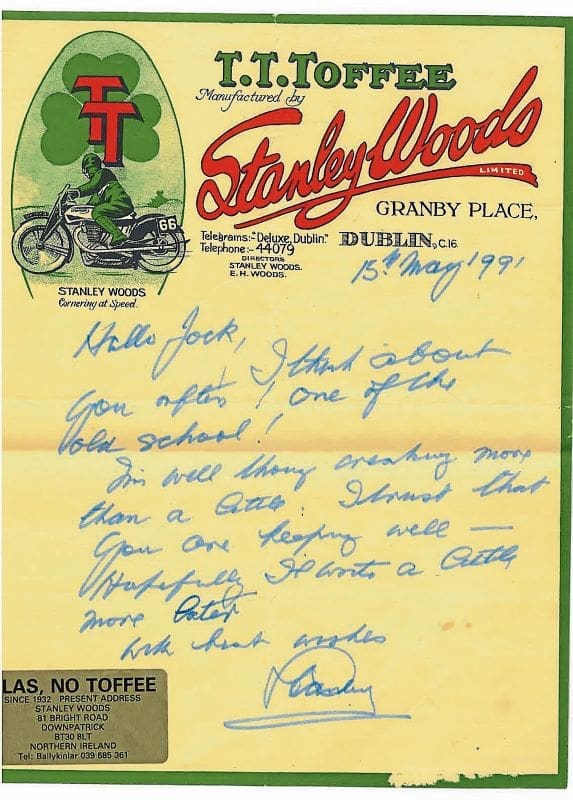

During the 1930s, Stanley became famous not just for his racing prowess and his superstar lifestyle – he and Mildred travelled the world in style – but for his toffee making, a throwback to his earlier life. He had his own factory in Dublin which manufactured ‘TT Toffee’ and always took boxes of the confectionery for the Scouts who manned the TT scoreboards.

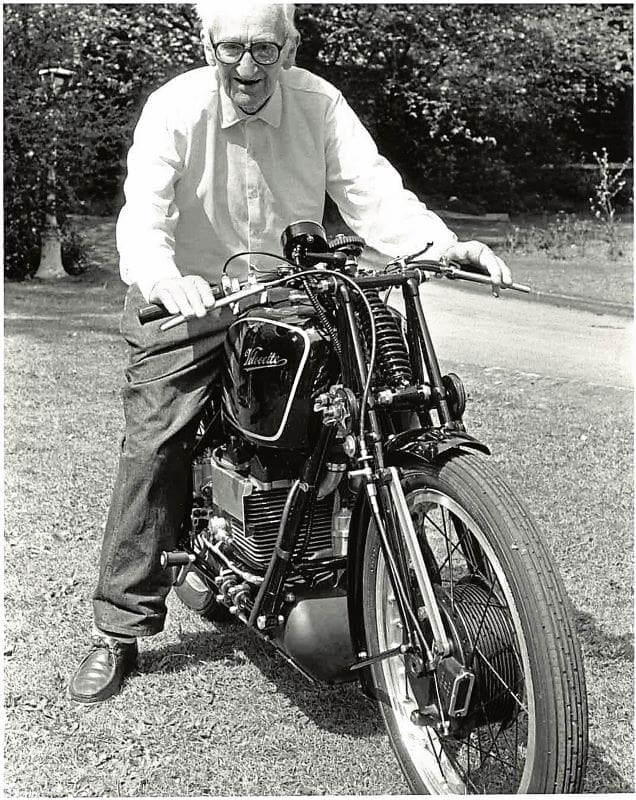

From 1936 to 1939, Stanley rode mainly for Velocette with whom he had a good relationship, even though it seems likely he was paid less than he had been at Norton. However, bonuses from his wins – and there were many, including TT wins for Velocette in 1938 and 1939 – allowed him a good living. Interestingly, given his views about the death of Jimmy Guthrie, he also rode for DKW at this time, although with limited success due to the fragility of the German supercharged machine.

The final TT victory

With the outbreak of the Second World War, all motorsport ceased and Stanley joined the Irish Army, rising to the rank of Major in the Fourth Cavalry Motorcycle Riders. He was in charge of motorcycle repairs and the training of motorcycle riders and his last duty before returning to civilian life was to organise the Cavalry Motorcycle display at the Royal Dublin Society in 1945.

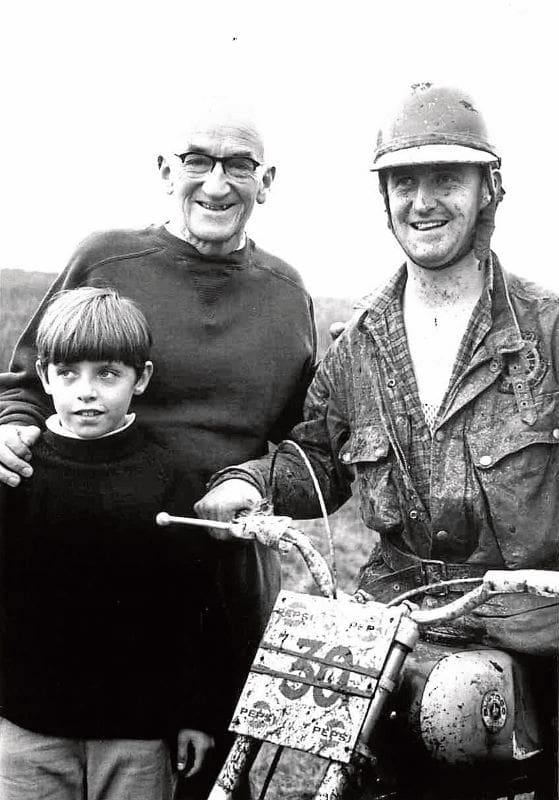

Ill health made it impossible for him to return to his road racing career although he had ended on a high note, winning the Junior TT – his 10th win – for Velocette in 1939. He went into business in the motor trade until retiring in 1966 and took up skiing along with trials and scrambles. In 1957 he returned to the Isle of Man for the Golden Jubilee of the TT and showed everyone how it was done, lapping the course on a 350cc Moto Guzzi at over 82mph. (He would do it again at the age of 87.) When Mike Hailwood finally beat Stanley’s record of 10 wins in 1967 one of the first people to congratulate him at the finish line was Mr Woods.

Some years before his death in 1993, Stanley donated his collection of trophies to the Ulster Transport Museum where an exhibition was mounted in his honour. However, he was an inveterate chronicler, note taker and diary keeper throughout his life and photographs and items he owned still occasionally appear at auction (at the recent Bonham auction at the Stafford show a selection of memorabilia was offered, including a Stanley Woods TT Toffee notepad and headed paper and a testimonial dinner menu).

Several riders have since equalled or surpassed Stanley’s 10 TT wins and, of course, the current magnificent record of 26 victories was set by another Irishman, the late Joey Dunlop. But before them all was Stanley Woods, a man who we can rightly claim to be the greatest TT rider of all time.