More than just being a staid ‘Mr Sensible’, the AJS 16MS offers surprising performance and plenty of period charm for modern riders.

Words: PHIL TURNER Photographs: GARY CHAPMAN

The April 1958 issue of Motor Cycling featured a full, front-page advert for the AJS 16MS. Above an image of two suitably-attired gentlemen, one astride and one behind two examples of the model, sat the ‘hook’: ‘A pleasure to own… a joy to ride…’ Beneath them a paragraph of copy extolled the machine’s virtues: ‘Fast and lively, yet extremely economical, the superbly finished, fully sprung 350cc OHV Model 16MS is equally happy when used for serious long distance touring with full equipment and a pillion passenger, for sporting purposes, or for daily transport.’

‘May we send you particulars?’ was – in modern advertising parlance – the ‘call to action’.

It was of course common practice for the front cover of weeklies to be adorned with a full-page manufacturer ad. What was slightly unusual about this example is that it signalled an easing of hostilities between AMC and the motorcycling press.

The relationship had started to turn sour in the early 1950s. Road testers had begun to notice – and highlight – issues with quality control and reliability and started drawing attention to a lack of technical innovation in AMC’s output. Management did not handle the criticisms well, and rather than accepting and addressing the issues raised, reacted defensively; the adversarial stance adding fuel to the fire.

Things deteriorated to such a point that AMC took the step of refusing to offer any machines to road testers, and pulled advertising budgets from their respective titles. The aim was to control the narrative around their products and avoid further damaging reviews, but it backfired, contributing to a further decline in the company’s reputation. Recognising the self-fulfilling prophecy, AMC eventually relented and by the close of the decade, tensions had eased, and the testing embargo was lifted.

Top brass

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s easy to look back on AMC’s reaction and resulting decisions with a critical eye, but it’s just as easy to comprehend why criticism of their products – in particular, the respective AJS and Matchless 350s – prompted such a response.

The G3/L’s performance during the war had furnished AMC with a reputation for making rugged, reliable machinery. Add to that their early innovations with the ‘Teledraulic’ oil-damped telescopic forks (the first of their kind fitted to a British machine), and the early adoption of swinging arm rear suspension, and it’s easy to see why AMC’s men in suits would be a bit miffed. They’d earned that reputation!

The G3/L had indeed proved itself as an incredibly worthy ally on the battlefield. It had a decent turn of speed and the aforementioned ‘Teledraulic’ forks provided a much more comfortable and stable ride than the ‘girders’ found on other dispatch mounts – the weight-saving design of the forks was the reason for the ‘L’ (lightweight) designation.

Add to that the bulletproof (not literally) OHV engine and you had the recipe for the perfect dispatching machine: reliable, comfortable and fast. Top brass were so impressed they bought 80,000 of them, and were in fact still buying them well into the mid-1950s.

Wartime configuration

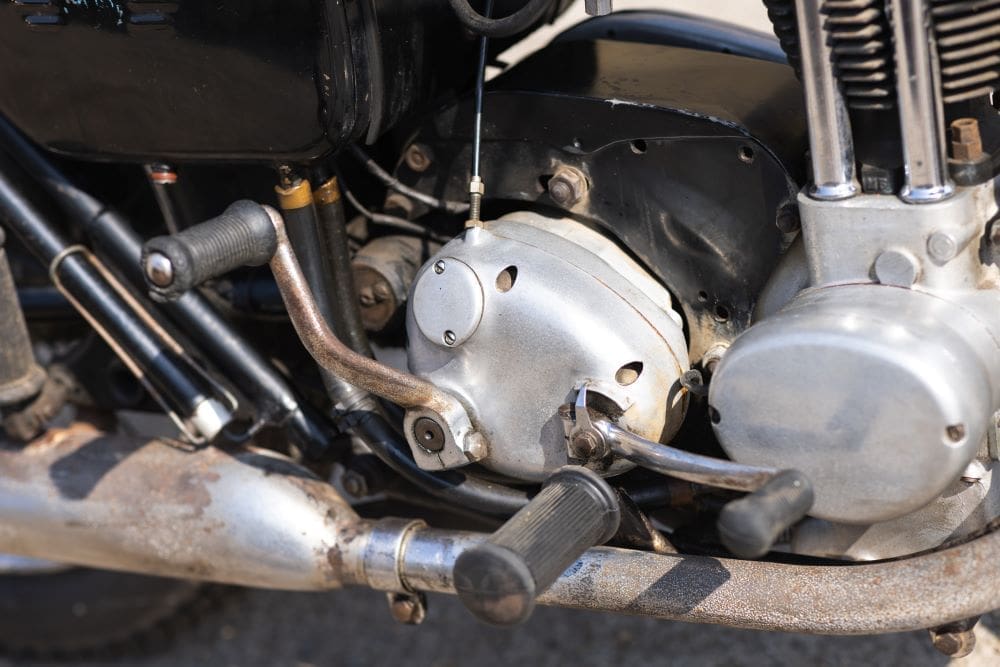

It was on this well-proven design that the new, 1946 range of 350 and 500cc AMC machines were based. All four were built on the same production line at Plumstead, and aside from the badging ‑ the 350s were either G3/L or Model 16, the 500s G80 and Model 18 ‑ the only real difference between them was the positioning of the magneto: it sat in front of the cylinder on AJS models, and behind it on their Matchless equivalents.

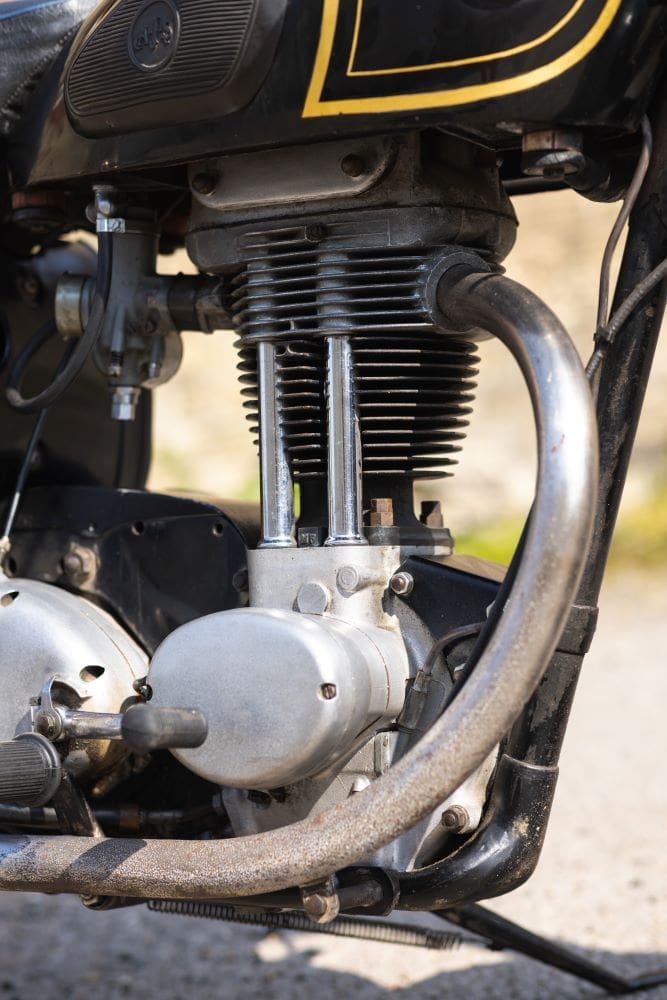

Aside from their internal dimensions, the 350cc and 500cc engines were also identical. Both had vertically split crankcases and a built-up bottom end; the crank ran on a combination of bearings ‑ two ball races on the drive side and a bush/roller setup on the timing side ‑ a one-piece connecting rod completed the assembly, supported by roller bearings.

Twin cams and pushrods housed in external tubes took care of valve actuation, with coil springs ensuring their return. A unique worm-driven rotating plunger pump handled engine lubrication.

Drive was transferred through a single-row chain primary, a wet multiplate clutch and Burman four-speed gearbox.

Electrics were of course six-volt, and fuel was delivered by a standard Amal carburettor.

The chassis retained the wartime configuration of a rigid rear and Teledraulics at the front.

Candlesticks and jampots

Development would follow the usual ‘evolution, not revolution’ path and timescale. The 1948 season saw a couple of notable tweaks. Hairpin valve springs swapped in for the older coil type, and swinging arm rear suspension became an option. The initial design featured slender shock absorbers with twin coil springs and dampers, earning the nickname ‘candlesticks.’ These skinny units were eventually deemed a bit light on damping and replaced in 1951 with sturdier items boasting increased oil capacity ‑ christened, with equal creativity, ‘jampots.’ Additionally, a lightweight alloy cylinder head replaced the previous cast iron version.

The 1952 models were marked by a lack of nickel/chrome plating: a consequence of the Korean War. Additionally, Matchless owners saw the magneto repositioned ahead of the cylinder for that year. This was a particular boon for them, as the dynamo had previously been tucked awkwardly beneath it. Servicing it meant removing the timing cover, which inevitably threw timing settings out of whack.

A dual seat replaced the single saddle in 1953, and an Amal 376 Monobloc of 1 inch diameter was fitted for 1955. In 1956, AMC’s own four-speed gearbox replaced the Burman; AMC replaced the Burman gearbox with their in-house four-speed unit in 1956. Girling shocks replaced the jampots a year later. In 1958, the march of progress arrived with the adoption of alternator electrics.

Shortcomings

The problem was that the reputation the G3 had built during the war was so good, that any Matchless or AJS that followed it had to perform just as well, if not better; AMC couldn’’t afford to let standards slip.

Initially, they didn’t. Sensible upgrades to engine internals and an improved electrical and charging system helped maintain that oh-so important reputation for reliability; while the early adoption of swinging arm rear suspension (unlike much of the competition, AMC did have the foresight not to go down the plunger blind alley first), an aluminium cylinder head and tweaks to the Teledraulics kept both the G3 and 16M running with the pack.

Unfortunately, the improvements did little for performance, and facing stiff competition from more innovative designs ‑ from home and abroad ‑ AMC 350s quickly became overweight, underpowered and outclassed. Problems with quality and discrepancies in performance between models also started to creep in.

It was of course the duty of road testers to point out such shortcomings when offering prospective buyers an assessment of model options ‑ and one can’t argue that it was within AMC’s power to do something about them, of course – but it must have cut the factory deeply to have a model line they held so much pride in, dismissed in such a way.

AMC would finally give their 350s a much-needed performance boost in 1963, with an increased bore and shorter stroke, higher compression ratio, bigger valves and carb.

It turned what were by then very old-hat and mundane middleweights into thoroughly usable and rideable machines. The journalists loved them, but by then it was too late.

A sure-fire case

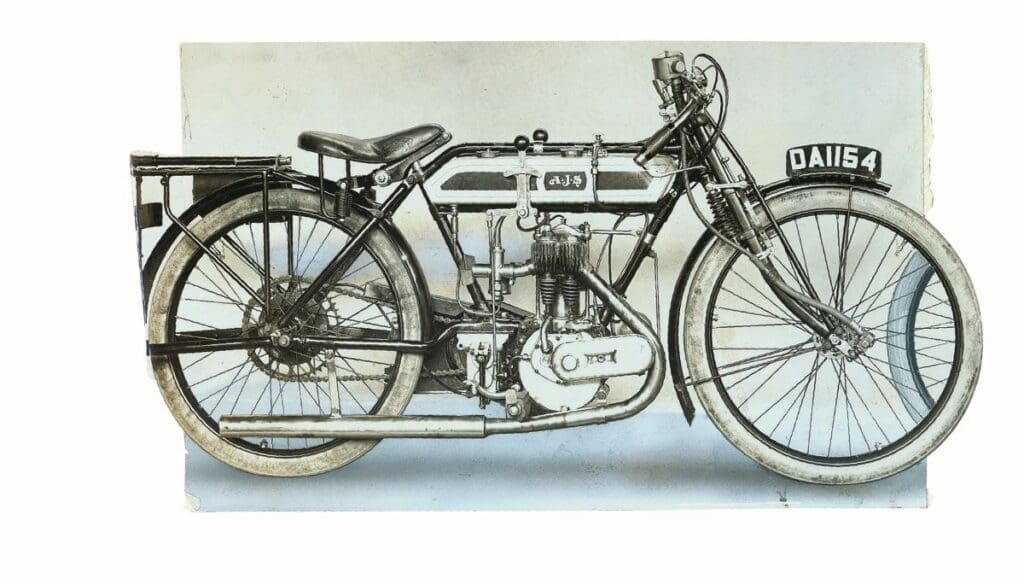

This particular example of the AJS 16MS (the S stood for ‘sprung’ highlighting the addition of the swinging arm rear suspension) – a 1959 model – caught editor James’s eye as he and I were perusing Andy Tiernan’s stock one sunny spring afternoon. Just new in stock, it had been owned by the same Norfolk family for the last 40 years.

The MS stood out to him not for its rarity, sporting achievements, or its gleaming, just-restored condition, it, in fact, has none of the above and as a result, was available for just £2850. It didn’t hang around long and soon sold – but have a look at www.andybuysbikes.com for similar machines on offer.

It’s often asserted that motorcycling – particularly classic British motorcycling – is an expensive hobby, but here’s a sure-fire case to dispel the myth: for less than the price of a Chinese-made 125cc, this humble AJS 16MS provides an entry into the classic motorcycling fraternity, a rolling restoration project for those looking for a weekend hobby, something to join local club runs with, or bimble about the back lanes on a sunny Sunday, or even an economical commuter ‑ the UK average is apparently only eight-miles each way. Free road tax, no mandatory MoT to worry about, low-cost classic insurance, and you don’t need a computer diagnostics machine and a degree in engineering to fix it; an annual subscription to the Owners’ Club would give you access to spares, support, and a host of other benefits besides.

An almighty crackle

That’s certainly an appealing prospect on paper, but would a budding young motorcyclist find the 16MS a little too tepid for his or her tastes? Well, it certainly didn’t feel like it was lacking in get up and go, as I pulled out of Andy’s yard onto the somewhat hectic stretch of road leading to Framlingham town centre.

Fairly brisk acceleration was needed to avoid interrupting the frantic flow of traffic and as I twisted the MS’ throttle, I was most relieved – and pleasantly surprised – to find its performance wasn’t lacking: the 347cc single pulling hard, and letting out an almighty crackle from the exhaust, worthy of something twice its capacity.

I was also happy to find the clutch featherlight and perfectly adjusted, and the four-speed gearbox equally easy and positive to work – no false neutrals or clunky changes, and no frantic stamping on the lever.

In just a few minutes I was past the lunchtime rush, and heading out of town, the motor feeling completely unflustered, strong and solid enough to keep it there as long as I needed it to.

The physical dimensions and weight of the 16MS give it a real ‘big bike’ feel; the seating position upright, the seat large and comfortable and the distance between it, the handlebars and footpegs allowing plenty of room to stretch out. It also carries its weight well and manhandling it isn’t difficult either – at rest it does still feel like a lightweight.

The somewhat chunky cycle parts also do a good job of making the Ajay feel like a much bigger bike in the turns too; the Teledraulics and Girling shock absorbers do a good job of staying poised over bumps and ruts in the road surface, handle fast direction changes with minimum fuss, and hold the line well. Great fun!

Given enough forethought, the five-inch SLS drums front and rear – although far from modern disc-brake standards – offer enough stopping power and control to calm progress.

‘May we send you particulars?’

It’s fair to say AMC’s singles haven’t really ever managed to shake off the ‘Mr Sensible’ image they picked up in the late 1950s. As an option for a prospective classic buyer today though, the negatives contemporary road testers picked up on, suddenly become positives and that April 1958 AMC advert suddenly sounds quite true: ‘Fast and lively, yet extremely economical, the superbly finished, fully sprung 350cc OHV Model 16MS is equally happy when used for serious long-distance touring with full equipment and a pillion passenger, for sporting purposes or for daily transport.’

I think I’d definitely say, ‘Yes, you may send particulars…’

Famous 350cc Ajays

Though perhaps Velocette might have claim to be the most famous makers of 350cc models, AJS also possessed an impressive record in that class, one backed up by myriad competition success.

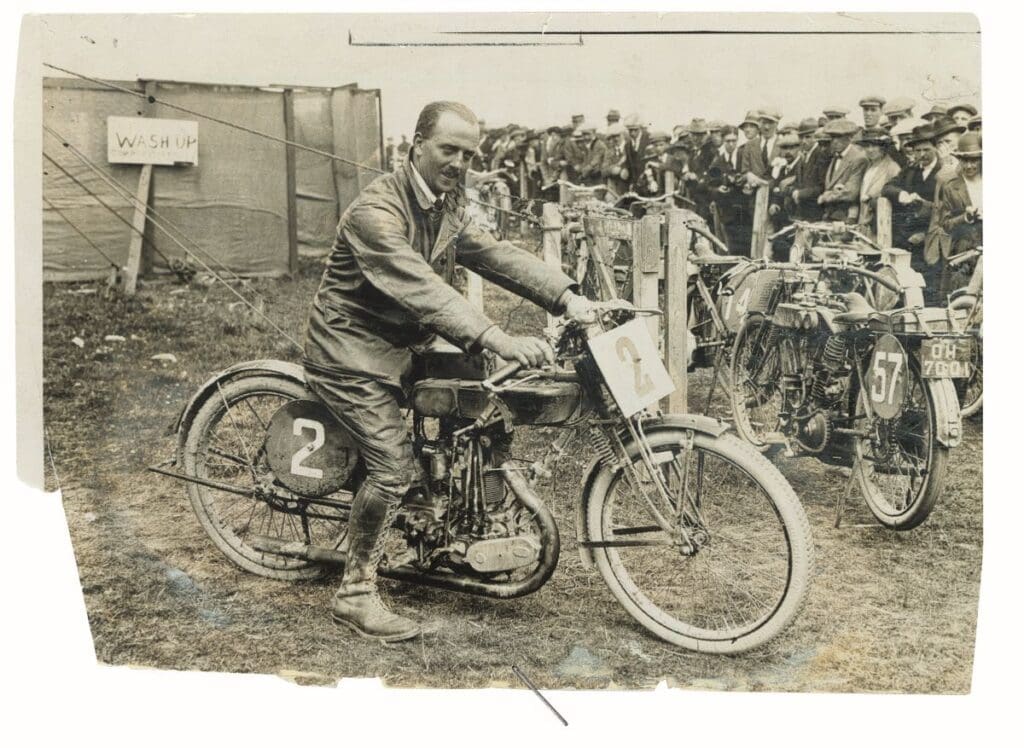

The first all-AJS production motorcycle made, went on sale in 1910, being a 292cc four-stroke, side-valve single. The new AJS quickly established a solid reputation and with the introduction of a Junior TT, AJS was at the forefront and by 1913 a full 350cc model was good enough to run as high as fourth, before problems (largely punctures) dropped it to ninth.

But in 1914 came the first successful AJS 350cc racers, as Eric Williams won the Junior TT, with team-mate Cyril Williams (no relation) runner-up, and other Ajays fourth and sixth. These machines were side-valves, though did boast four-speed gearboxes.

The TT didn’t return until 1920 – but AJS won again, the new, soon-to-be-legendary Big Port ohv models proving a class apart. The most famous 350cc AJS victory, though, was to occur in 1921 when Howard R Davies won the 500cc Senior TT on his 350cc AJS; that same year, AJS were one-four in the Junior race for good measure. There was a win in the 1922 Junior TT too, but Big Ports weren’t to claim another outright Isle of Man success. But the reputation as one of the most exhilarating machines from the period was cemented.

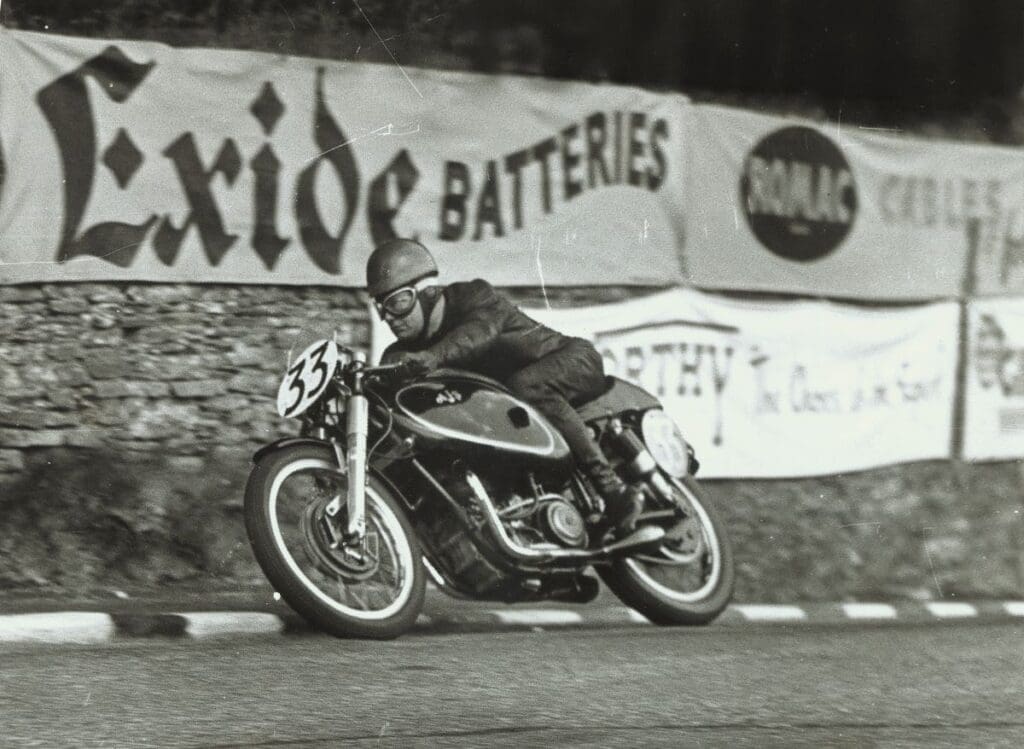

After the demise of the original Big Port, AJS made sporting 350cc ohc models and enjoyed modest success, though it was the post Second World War 7R which was the next, famous 350cc AJS. The model took several Manx GP wins in the 1950s and early 1960s, but the most famous victory came in the 1954 Junior TT, when Kiwi Rod Coleman rode the three-valve 7R3 to AJS’s last TT win. There’d have been another Junior TT success in 1961 for a (two-valve) 7R, but a broken gudgeon pin eliminated Mike Hailwood’s machine, when leading, just 14 miles from home.

That same year, 1961, did however see a famous 350cc AJS victory – Gordon Jackson’s ‘one dab’ Scottish Six Days Trials win on his works machine, registered 187 BLF, which is probably the second most famous trials machine in the world. It, incidentally, now resides in Sammy Miller’s New Milton, Hampshire museum, alongside GOV 132, Miller’s own Ariel, the most famous trials machine ever. But the AJS is probably the best-known 350cc trials motorcycle of all time, a fitting memorial to the marque’s success at that engine size.