Was the last of the triples the best of the bunch? Frank Westworth thinks so. Well, he thinks so today, at least.

Photos by Chris Spaett, Frank Westworth

How come – I asked myself while I was out aboard a really rather fine Trident the other week – how come I don’t have one of these? The reason I don’t have a T150 Trident is simple: any bike I’d like to ride a decent distance needs to have an electric hoof, and not entirely because I have become idle in my old age, although I’m sure that’s part of it. As I sailed back to base on that particular T150 – seen in these grimy pages a couple of issues back – I asked myself once again: why don’t I have an electric start Trident? And I have no answer for this – apart from one. They do sell for a lot of money – except when I’m the one doing the selling rather than the buying, as always.

Which is something of a warm topic around these parts lately. That old conundrum of cost versus value. I’d been chatting with a pal – a pal with a self-raising Trident, in fact – and he was disguising his understandable smugness and possibly attempting to cheer me up and dilute my understandable envy by remarking that I could buy one and a half brand new Triumph Tridents for the money he could sell his old, fairly tired Trident for. I was not encouraged, not really, but it’s a good point.

And oddly enough, along with St Ollie Hulme of this parish, I’d been shambling and bouncing around on a brand new Triumph Trident just a couple of days earlier. It doesn’t appeal to me at all, although I am sure that it’s a wonderful machine in every way. Unlike my last foray into the immersive world of T160 Tridents, I’m sure that ownership would simply be a matter of going off for a ride any time I felt like it – as indeed it is with our own modern Triumphs, of which we have a fine pair. Both twins, however.

There is of course little logic involved in choosing to spend a lot more on an old bike than on a new one, and as folk keep telling me that prices of 1970s clunkery are falling, maybe even the smug pleasure of being able to avoid depreciation is fading away. Not that I care about that. Not really. Although others have very different views. I’ve never entirely understood the motorcycle as investment notion. Returning to that falling prices theory, I must say at this point that the prices of bikes I would actually want to buy appear to be rock-steady and largely too high for my wallet.

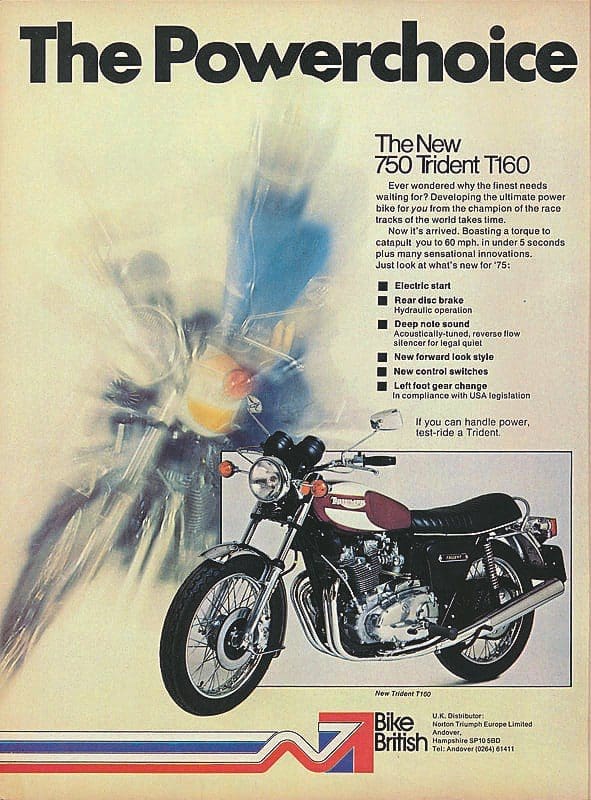

Isn’t it remarkable what a chap can think about while hooning about on a really great motorcycle? If I need to offer an excuse it can only be that I have ridden a lot of Tridents, so no longer marvel at what a stunning achievement they were for the otherwise staid British industry of the late 1960s. Like lots of folk, I wonder how different the world could have been if Triumph had launched their original triple in the trim of the T160 instead of the earlier T150. Just think: radical, almost beautiful styling, a disc brake at each end, five speeds, and that all-important electric hoof to eliminate the tedious leaping up and down at start-up time. Many years ago I swapped between a 1969 Honda CB750 and a 1976 T160 Trident for a story, battering around the roads of rural Cheshire with a friend – a friend who did actually prefer the Honda. I, on the other hand, was utterly smitten by the Triumph. I even attempted to buy it, but the owner refused.

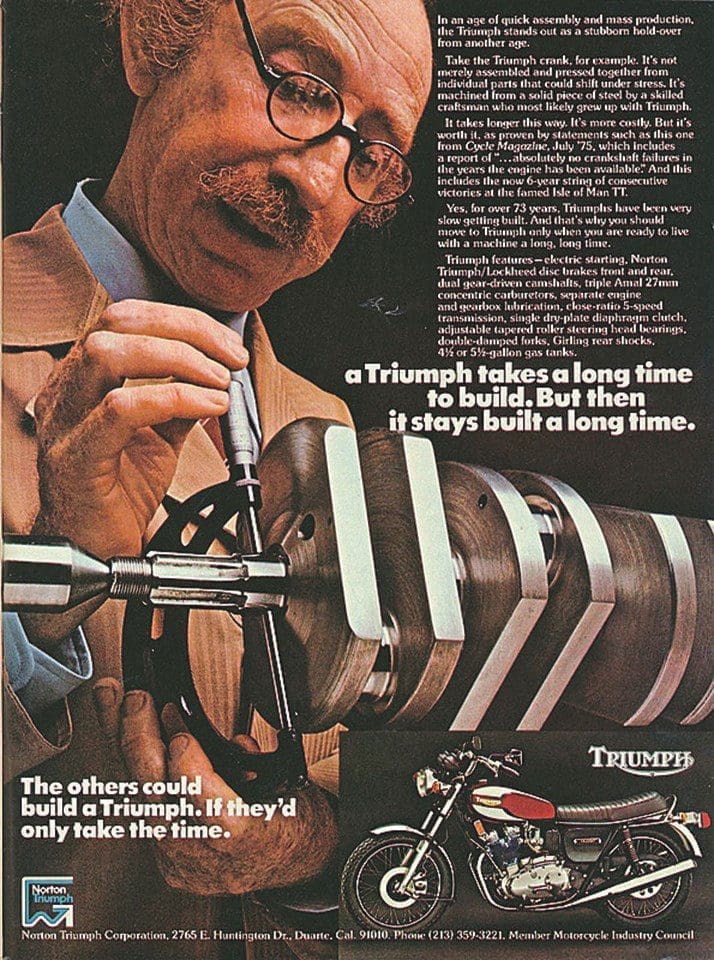

Anyway, back to the machine you can see here. Looks great, starts on the button, sounds awesome. That’s it; the abbreviated road test. Who needs more before parting with rather a lot of money? Yes; so would I.

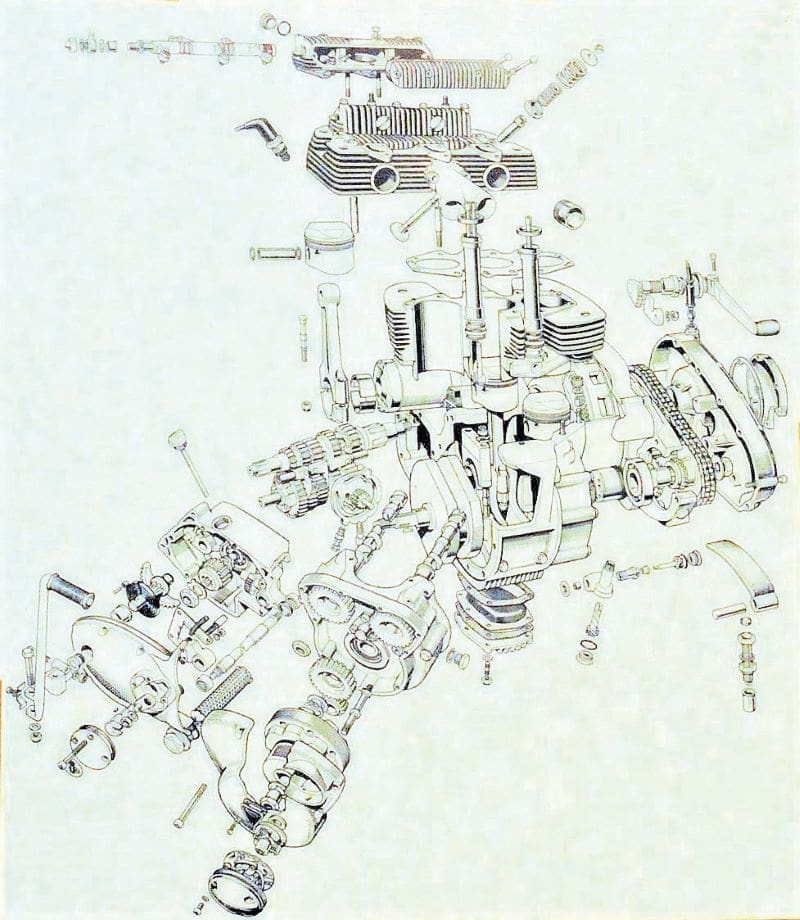

One of the many slightly amazing things about the T160 – not just Tridents in general, although their entire history is seriously remarkable – is just how many changes were made while developing it from its predecessor. Given that parent company NVT were not exactly awash with cash and were mired in relentless industrial trouble, it always comes as a fresh surprise when I read up once again on the development story of these machines. I would bet that a vast number of unpaid overtime hours went into it.

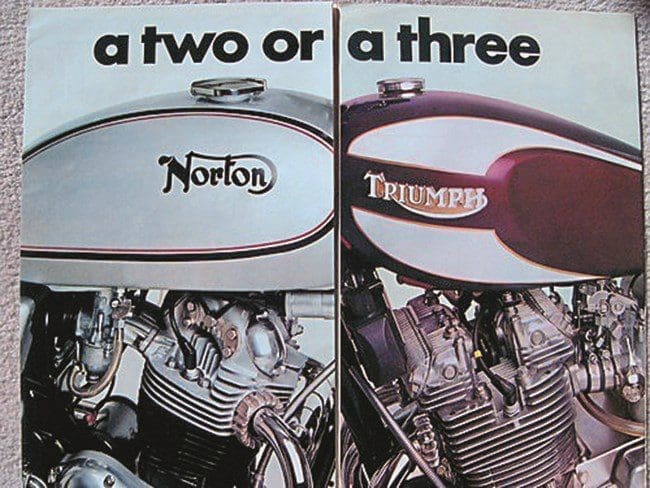

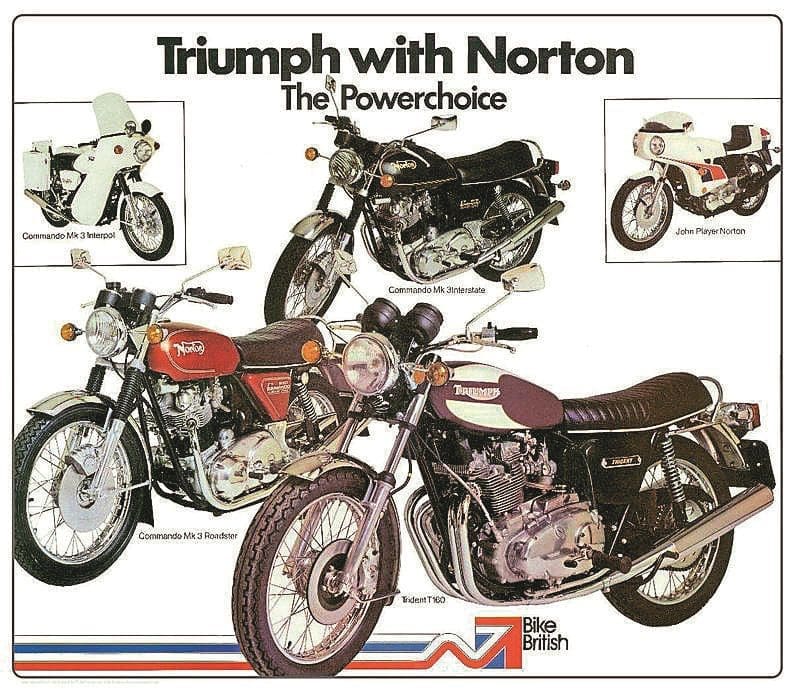

The most obvious changes are visual – of course they are. When the model first appeared, we all sneered that Triumph had adopted the slanted engine of sadly departed BSA’s own triple, the Rocket 3. I could probably confess that I prefer Rockets 3 to most T150 Tridents, strangely enough. But in fact the major castings which provide the forward inclination are unique to this Trident, not least because the BSA’s lean angle was a weedy 12°, whereas the Trident’s is an heroic 15°. Please don’t ask me why, because I have no idea. Back then, we all assumed that the tilt was to provide space for the starter motor and associated gubbins, but it proves to be perfectly possible to fit an electric hoof to a T150. Check out the John Young machine in RC 209. Other probable causes were to make space for a much enlarged airbox to meet intake noise levels, and maybe to permit both lowering the main frame and raising the engine in it, both of which are unsung features of these machines.

And yes, although many fans know that the T160 frame was based on a ‘short’ design intended for production racing, most of us forget that the engine was moved upward by an inch and forward by half an inch. Only engineers will understand why, apart from a nod towards the engine’s width and ground clearance when racing, but it will explain why the T160 feels so different to its earlier brethren – which it does.

It would be possible at this point to list as many changes made to differentiate the T160 from the T150, but let’s go for a ride instead. There are lots of good books on the market which detail the changes and much, much else. Riding the bike provides a practical opportunity to feel those developments, and is a lot more fun than endless reading!

The later bike feels lower, for starters. You feel like you’re sitting lower, and there’s rather more air between your eyes and the top of the fuel tank. So it may come as a surprise to learn that although the T160 does indeed boast a lower seat height than the T150 – it’s a whole half inch. Them’s the facts – I looked them up. This is always a moment of wonder whenever I write up a T160 triple, because the seat feels and looks less well upholstered, the forks are shorter and have less travel, and the swinging arm is a little longer, all of which should lower the seat height. Half an inch. OK.

You will notice that I’ve parked myself on the bike before remarking upon its truly handsome good looks. That tank, those shallower side panels and the utterly glorious exhaust system are all deeply eye-catching stuff. And the rider’s eye is caught by a radically modernised instrument cluster, too. I shall say nothing about the handlebar switchgear for the moment.

There’s even a tickler for the centre carb, although the great tradition still seems to be to just tickle the outer pair of Amals and apply a little choke if it’s cold. If the ambient is mild, they start well with just a tickle or two. And a leisurely caressing of the big button which applies electrical urge to the starter motor.

An aside: back in the later 1970s when T160 Tridents were occasionally and seemingly miraculously available new, those few of my pals who risked financial ruin by buying one argued endlessly about the desirability of replacing the standard ignition arrangement, which involves three sets of points, one for each cylinder, with one of the new electronic devices, most notably that offered by Boyer Bransden. Everyone I knew fitted the latter, but not everyone else did the same, suggesting that the drop in voltage caused by the starter motor’s load on the battery stopped the coils firing. When the late John Anderson made my own T160 run properly, one of the changes he made was to convert it from a Boyer back to stock.

The only important thing here is that this machine fired up perfectly well with just a little encouragement from the right thumb. This is as it should be, of course. Only the outer pots burst into life at first, with the centre soldier leaping into action in under a minute. And although the idle from cold was lumpy, it was reliable. The mechanical thrash is unmistakeable, almost industrial, and all part of the bike’s individualistic charm.

The clutch is heavy. It just is. It’s a diaphragm spring device and works very well, but it’s heavier than I would prefer. As is the throttle. Plainly heaving up three carb slides requires greater effort than you might imagine.

All of which matters not a jot as you click into first (left foot; only fools try to select a gear with the brake pedal) and ease out the lever while raising the revs… What am I saying? You know how to do this. The engine has lashings of low down smooth torque, and first gear isn’t too high; trickling along while working out where to hang the hands and feet is easy enough.

The riding position is not great, he writes, feeling kind. Why are the footrests in such an awkward position? Both LP Williams and Norman Hyde could relocate them at a cost less than a whole arm and an entire leg, so why couldn’t Small Heath? The generous soul within me wonders whether, like the T140, the rests make sense with US export bars, but my own machine wore those for a while and it was still uncomfortable. Just another of life’s minor mysteries.

Such nit-picking fades away as soon as you get into the swing of the thing. VROOM! That’s what it does, with the often-reviled bean-can silencers sounding very nice indeed. I don’t know how or why, but the speedo on this machine over-read, which gave me a minor moment when we sailed into the first speed restricted zone. Up-shifts and down are easy and clean. When you choose to operate that little lever depends entirely on how rapidly you wish to accelerate, because these engines really do go well. They do not lunge at the horizon like their Mk3 Commando stablemates, but they gather speed pretty rapidly. Plainly the quoted power output of 58bhp involves some decently lively horses among that number, and it is sore tempting to treat the pistons to a little wide throttle encouragement. I was forced to do this, gentle reader, out of a selfless spirit of research. They go really well, these, flying through the lower gears with a unique soundtrack and little impression of effort, although the engine could not be described as free-revving. You’re always aware of the need to accelerate a lot of heavy metal down there.

It’s easy to sail by the legal limit in third, a nice long gear which will also provide fine speed control via the engine braking, which is considerable once it’s spinning past 4000rpm or so, and considerably more so 1000rpm above that. Which is as fast as I’d travel on someone else’s bike.

Speaking of which, this machine belongs to long-time RC supporter Stewart C, and it’s for sale. Where was I? Oh yes…

Engine braking. There’s a lot of good to be said for controlling your main road speeds mainly by judicious use of the throttle, avoiding hard acceleration and hard braking too. This was how I was taught to ride: using the engine saves on brake wear, which is important when you’re skint, and accelerating more gently saves fuel and wear and tear of the entire powertrain. I suspect that anyone who can afford to run one of these need not worry about things like that, but the front brake is a not a great device, to be honest, so engine assistance is welcome. The rear’s better, but it’s easy enough to lock it up. ABS for road bikes was a long way away in 1975. The brakes are OK used together, but this is a fast and heavy machine – 503lb, up from the T150’s 460 – and takes some stopping should a chap be pressing on. My own machine had twin discs and racing calipers – worth every one of the considerable number of pennies it took to fit them.

And speaking of bends; the handling is excellent. No ifs no buts; it’s just excellent. It is dead easy to touch down on either side without playing racers – and the big fat rubber footrests simply slide along a smooth surface. You’ll feel a growing resistance to leaning further, but hey – racers we are not, and bendswinging is a delight.

Unlike the suspension, which is both very firm and of short travel. I would like to say that this is to keep the handling precision at the top of its class, but it just feels like short travel for its own sake. Rowena of this parish has a modern Triumph Bobber for pleasure rides, and it’s the same: very firm, almost hard, and for the same reasons. Keeping things low means short suspension travel. If you want BMW suppleness – buy a BMW. And leg extensions. To be honest, one of the several appealing features of the T160 is its low seat height – which turns out not to be particularly low, it just feels like it.

The triple feels light, too, even when mauling it around using the power of the push, rather than the engine. The difference between reality and perceptions can be quite striking. I suspect that a lot of this is down to the clever fuel tank design, because the bike does not feel wide, either, although it actually is.

I’ve said before – recently, too – that I’m not a great fan of 5-speed gearboxes. That statement was in the context of a T150 triple we featured a couple of issues back and remains the case. Except… it doesn’t. The 5-speeder on the T160 feels exactly right. The ratios are well chose, although top feels too low, and Triumph themselves altered the gearing during the brief lifetime of the model: changing both engine and clutch sprockets at least once. After riding this example, I decided that a tooth less at the rear wheel might make things a little more relaxed on those long dual carriageway hauls we’re all so fond of. And then of course I remembered that the last time I did a 100 miles or so on a T160 I was spotted by a CBG reader heading north on the M5 (the only way to navigate Bristol) while standing up because the saddle was killing me.

Better seats were available, and indeed they may still be available should you contemplate high mileages. And if you are indeed of that iron butt ilk, you might want to consider the engine’s vigorous appetite for fuel. Think about 35mpg – easily increased to 30mpg if the available performance is wrung from the engine. I’m always thinking personally when considering a borrowed bike, and this figure wouldn’t worry me. I can’t see that I would cover enough miles to make it a problem. Our noble sister Triumph – the glorious Blazer SS – appears to manage at least twice the distance on the same volume of fuel. Just saying.

Which is what it’s all about: compromise. Like all production motorcycles, particularly those produced under serious commercial constraints, the T160 is a compromise. The TR3OC – the very enthusiastic club for triple aficionados – currently have one of the few surviving 850cc T180 prototype engines as a project. Anyone who’s ridden an 850 conversion on a Trident knows all about the decent torque boost and its ability to provide enough grunt for a comfortable drop in the teeth of the rear sprocket. A factory 850 would be a fascinating bike to ride. More news as we get it.

Meanwhile, the roads were dry and the sun was attempting to shine. Time for another test lap, I think…