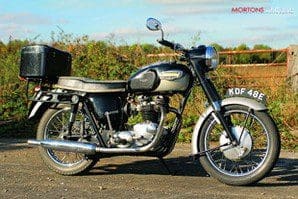

It required virtually no restoration and would have been relatively unremarkable, even for having been registered in the year after production ceased, but for the fact that it was 100 per cent original and in exceptional condition. It also came with a full history from the date of sale in 1967, by Triumph specialists H&L Motors of Stroud, in Gloucestershire.

The first purchaser was a mature rider from Oxfordshire, and MoT certificates confirm that he covered 1000 miles every 12 months. After five years, he left it with a local mechanic for a 5000 mile service. “Now, the mechanic never ever got round to servicing that bike,” Pete told me, “so eventually, the owner moved out of the area and sold the bike to the mechanic. But even then, it stayed where it was, gathering dust at the back of a garage for the next 16 years.”

Pete was alerted to the bike’s existence by one of his employees at British Gas, who had spotted it through an open doorway during a routine service call. Curiosity made Pete decide to go and have a look, even though the model was not one that he coveted, and his enthusiast’s eye soon noted its finer points.

“The asking price was £1000, which was quite a lot of money for any Triumph twin in those days, so I left it for a while,” recalled Pete. “Of course, every time I went to the village with my gas van, I had another look at it. One day, I took a rag and some polish with me, and began wiping away at a small section at a time. Well, I just could not believe my eyes when I saw the quality that was underneath all that dirt and grime! So I coughed up the £1000 and spent the next day at home, polishing the whole lot until it was gleaming and immaculate.”

“The asking price was £1000, which was quite a lot of money for any Triumph twin in those days, so I left it for a while,” recalled Pete. “Of course, every time I went to the village with my gas van, I had another look at it. One day, I took a rag and some polish with me, and began wiping away at a small section at a time. Well, I just could not believe my eyes when I saw the quality that was underneath all that dirt and grime! So I coughed up the £1000 and spent the next day at home, polishing the whole lot until it was gleaming and immaculate.”

Pete subsequently added another 14,000 miles of his own to the recorded mileage of 4500, but still the engine assembly remained just as it had been, the day it rolled off the production line at Meriden in the autumn of 1966. He replaced only the contact breaker points (recently upgraded to electronic ignition), both tyres and a single spoke in the rear wheel, while the rear carrier and top-box were transferred from a Norton ES2 that he had previously used for touring duties.

The model 6T Thunderbird was marketed as a roadburner when it first appeared in 1949, its engine being essentially a bored and stroked version of the 5T Speed Twin design that had been relaunched after WWII. The latter’s twin-cylinder 490cc 5T design was strengthened internally, with a reinforced big-end assembly and a more efficient oil pump. Additionally, the gearbox was redesigned to facilitate engagement and the clutch received an extra plate. The 6T’s additional 159cc provided an extra seven horsepower that went some way towards satisfying postwar clamour from the American market for affordable high performance, without sacrificing reliability. It was so immediately successful that, from the next year onwards, more Triumph twins would be sold in the USA than in Britain.

Credit for the Thunderbird concept rests with Triumph’s managing director of the time, Edward Turner, although much of the production engineering work was undertaken by Jack Wickes at Meriden. The Thunderbird name was allegedly inspired by a motel in Florence, South Carolina, at which Turner had stayed during an earlier tour of the USA. The result, painted an understated grey-blue, was arguably the most desirable street motorcycle of the 1950 season.

Credit for the Thunderbird concept rests with Triumph’s managing director of the time, Edward Turner, although much of the production engineering work was undertaken by Jack Wickes at Meriden. The Thunderbird name was allegedly inspired by a motel in Florence, South Carolina, at which Turner had stayed during an earlier tour of the USA. The result, painted an understated grey-blue, was arguably the most desirable street motorcycle of the 1950 season.

A three-machine demonstration launch at Montlhèry Autodrome, near Paris, recorded an average running speed of 90mph over 500 miles, with a top speed in excess of 100mph. The Motor Cycle’s man at the scene, George Wilson, put in three laps on one of the same machines directly after the test and called its performance ‘phenomenal’, feeling the engine to be working no harder at 100mph than his own Speed Twin did at 80. To these superlatives, Triumph then added an astonishing fuel consumption figure of 155mpg, following a 30mph economy run over a 10-mile road circuit during the summer of 1952, with only simple modifications to the carburettor needle, top-gear ratio and tyre pressures.

The 6T was superseded in outright performance terms by the 42bhp Tiger 110 (nicknamed the ‘Tiger-bird’ in the USA) that appeared soon after Marlon Brando rode a Thunderbird into cinemas as The Wild One during 1953. This at least allowed the 6T to build a new reputation as a sporting tourer and police mount, for which its capabilities were enhanced by new alternator electrics.

For 1955, a swinging-arm frame and larger main bearings added further integrity, while an Amal Monobloc carburettor replaced the SU instrument for 1959, when the colour scheme became charcoal-grey and black. The following year brought the adoption of a twin-downtube frame with new front forks and petrol tank, and 18-inch diameter wheels. Styling now followed a lead set by the smaller twins, so that a ‘bathtub’ fairing obscured most of the rear wheel.

For 1955, a swinging-arm frame and larger main bearings added further integrity, while an Amal Monobloc carburettor replaced the SU instrument for 1959, when the colour scheme became charcoal-grey and black. The following year brought the adoption of a twin-downtube frame with new front forks and petrol tank, and 18-inch diameter wheels. Styling now followed a lead set by the smaller twins, so that a ‘bathtub’ fairing obscured most of the rear wheel.

An alloy cylinder head raised the compression ratio slightly for 1961 and the front brake diameter increased, while ‘Slickshift’ semi-automatic clutch operation was discarded following just two years of fitment. The entire 649cc twin-cylinder range received unit-construction engines in late 1962, four years after the 5T Speed Twin had become the 5TA. The unit 6T Thunderbird now reverted to a single front downtube frame with bolt-on rear sub-frame and cycle parts painted silver and black, although the model designation did not change.

The rear fairing reduced considerably in size for 1963 and The Motor Cycle tested one at 104mph, showing it had lost none of its performance. Revised front forks and 12 volt electrics followed in 1964, and the headlamp nacelle was finally abandoned along with rear enclosure, a few months prior to the model’s discontinuation in July 1966.

It could be argued the 6T Thunderbird was the first popular ‘superbike’, combining high-speed cruising with superior overtaking power at an affordable price. It was an attractive package that defined exactly what a new generation of owners wanted from a postwar Triumph twin. Its handling and brakes matched the performance and it offered reliability and comfort to boot. Only when Triumph and its specialist suppliers boosted variations of the engine beyond 650cc and a rev limit of 6500rpm did its design limitations, in terms of rider comfort and mechanical wear, become apparent.

Pete remained enthusiastic about his Thunderbird after 20 years of regular use. “I love it,” was his verdict. “I find it reassuring that that everything is exactly where it should be, not like on some of my vintage bikes, where the clutch is a handle on the petrol tank and the throttle is a little lever. I like its solid feel out on the road, knowing what it’s going to do and what it’s not going to do in any situation. Above all, I know it’s never going to break down on me and with just one carburettor, it’s as smooth as you like, too.”

Pete remained enthusiastic about his Thunderbird after 20 years of regular use. “I love it,” was his verdict. “I find it reassuring that that everything is exactly where it should be, not like on some of my vintage bikes, where the clutch is a handle on the petrol tank and the throttle is a little lever. I like its solid feel out on the road, knowing what it’s going to do and what it’s not going to do in any situation. Above all, I know it’s never going to break down on me and with just one carburettor, it’s as smooth as you like, too.”

I was excited at the prospect of riding this example, still with a relatively low mileage, although my initial impressions of its mechanical condition were decidedly average. The engine started first kick, but first gear selection was noisy and finding neutral was quite a precision affair. Subsequent gears engaged positively enough, while acceleration was brisk and decidedly Triumph-like, but what impressed me most was how refined the engine felt at legal road speeds. Mechanical clatter from the top end was minimal and the engine remained oil-tight, even when hot. I’d never ridden a Meriden-built Triumph roadster that felt as good as this one, not even a factory-fresh Bonneville from the last days of the workers’ co-operative.

The chassis absorbed slight shakes caused by uneven wear of the front Avon Speedmaster tyre, tracking accurately through the lanes north of Swindon to Highworth, located at the southern gateway to the Cotswolds. Betjeman called this elevated town, ‘…extraordinary, because it has more beautiful buildings than ugly ones,’ and there is an unassuming beauty about the whole area, which includes the small obelisk marking the grave of 007’s creator, novelist Ian Fleming, who was buried at nearby Sevenhampton just two years before this bike was manufactured.

The Triumph Thunderbird certainly exhibited a James Bond-like capability for quick and decisive action in a tight spot. There was plenty of power in the overtaking range, without the need to drop a gear and without detriment from the larger engine size in terms of vibration. It’s a fair bet this engine had always operated at around 60-65mph, which is probably why it was still running smoothly. Engine braking compensated for an unimpressive single leading-shoe front brake, backed up by a very effective rear unit, and I found the sound from the pair of free-flowing silencers just as evocative on deceleration as when the throttle was twisted.

The Triumph Thunderbird certainly exhibited a James Bond-like capability for quick and decisive action in a tight spot. There was plenty of power in the overtaking range, without the need to drop a gear and without detriment from the larger engine size in terms of vibration. It’s a fair bet this engine had always operated at around 60-65mph, which is probably why it was still running smoothly. Engine braking compensated for an unimpressive single leading-shoe front brake, backed up by a very effective rear unit, and I found the sound from the pair of free-flowing silencers just as evocative on deceleration as when the throttle was twisted.

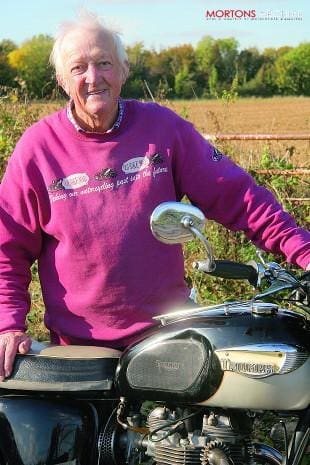

The Latin inscription on Fleming’s tomb, ‘Omnia perfunctus vitae praemia marces’, echoed Pete’s battle against serious illness during this time, when the only treatment I could prescribe was a spin into the countryside on motorcycles. I’m happy to report that the joy of being in the saddle after weeks of toxic treatments was written all over Pete’s face on that bright autumn afternoon. Sadly, he passed away just four months later, aged 67. His legacy included top-class awards from his peers for vintage motorcycle restorations, the most recent of which were for the 1911 Bradbury that featured in these pages (TCM January 2010) and which Pete lived long enough to see displayed at the NEC Show last December. As a man, I likened him to the machine that you see here: understated, authentic and highly original, with timeless qualities that any true enthusiast would recognise.

Anyone who understands old motorcycles knows better than to judge a book by its cover, which is how Pete came to acquire this beauty of a motorcycle. He might never have contested a sartorial concours d’elegance, but instead put all of his energies into making his show bikes immaculate. The Thunderbird was unusual for requiring less work than any of his other machines, but its owner’s enthusiasm for originality more than made up for this, as was evident when he remembered to tell me that its wheels still carried their factory-fitted balance weights. “Look!” he cried in his rich Wiltshire accent, pointing to the wheel rims, “Them chrome bloody knobs, ain’t they lovely?” No one could derive more pleasure from such simple details than Pete and I never knew a more self-effacing chap.

Anyone who understands old motorcycles knows better than to judge a book by its cover, which is how Pete came to acquire this beauty of a motorcycle. He might never have contested a sartorial concours d’elegance, but instead put all of his energies into making his show bikes immaculate. The Thunderbird was unusual for requiring less work than any of his other machines, but its owner’s enthusiasm for originality more than made up for this, as was evident when he remembered to tell me that its wheels still carried their factory-fitted balance weights. “Look!” he cried in his rich Wiltshire accent, pointing to the wheel rims, “Them chrome bloody knobs, ain’t they lovely?” No one could derive more pleasure from such simple details than Pete and I never knew a more self-effacing chap.