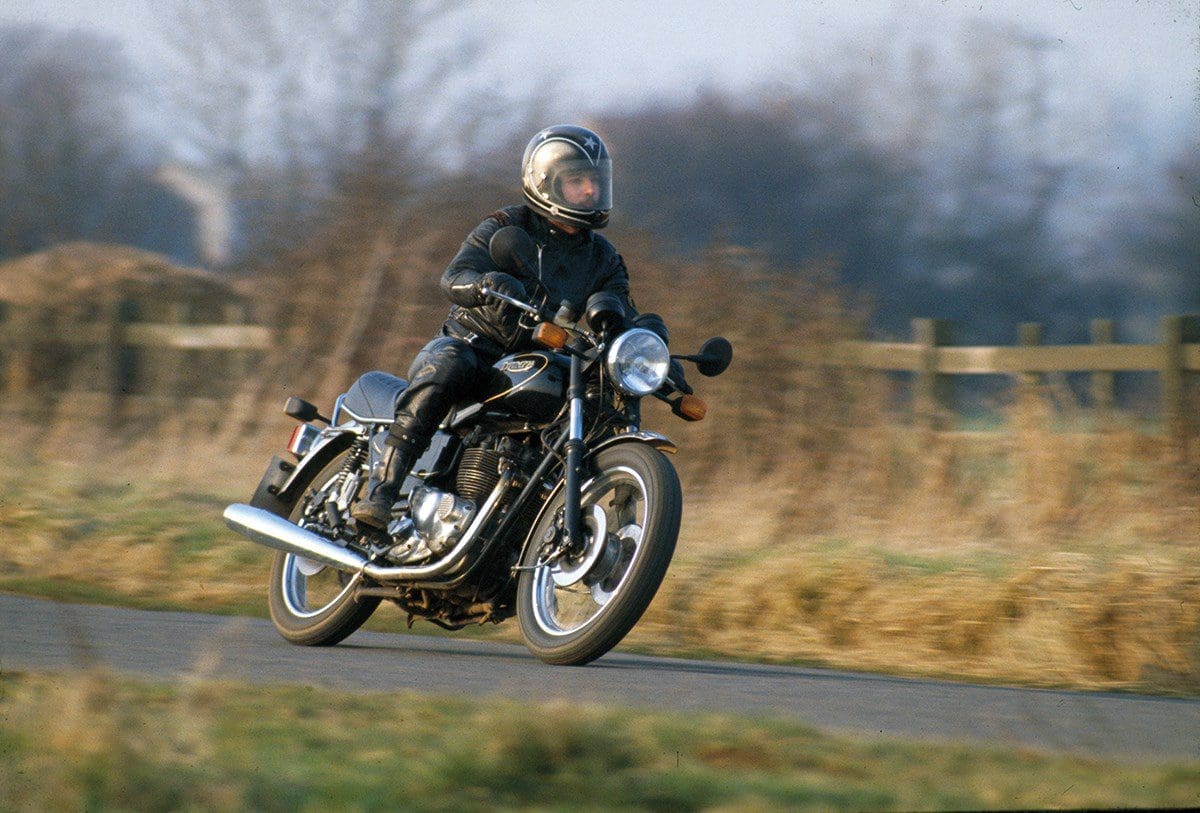

The eight-valve Bonneville twin which could’ve perhaps been original Triumph’s saviour.

The ultimate Meriden twin? Perhaps it was, but, like so many things in the final 20 or so years of the ‘original’ British motorcycle industry, 1983’s TSS was more an example of what might’ve been, rather than what actually was.

It’s reported that around 440 of the genuine-120mph topping TSS 750cc twins were made – but they were also beset by niggling problems, under-developed, and something of a final hurrah that, with a little bit more thought and effort, and finance, could have perhaps been a machine that would’ve eked a bit more out of the famous old engine, albeit it wasn’t ever going to be a long-term solution. Though that may have come in the form of the 900cc DOHC twin that was also on the drawing boards as the lights dimmed, and then finally went out at Meriden.

The story of the TSS can be traced to the late 1960s, when Weslake (founded by Harry Weslake and famous for all manner of work, notably the engine in Dan Gurney’s race-winning Formula 1 car, Jaguar and Vanwall car work, speedway, aero and marine engines, among others) produced an eight-valve cylinder head kit, which could be fitted onto a Triumph bottom end. It was originally supplied by the Rickman brothers, makers of Metisse motorcycles, though later supplied by Weslake themselves. The kit upped capacity to 686cc and featured paired valves, operated from the pushrods by forked rockers. Importantly, it gave a useful performance boost.

In 1976, the rights to make the Weslake passed to the company owned by Dave Nourish, who died in the autumn of 2021. His Nourish Racing Engines (NRE) business was heavily involved in speedway, preparing Peter Collin’s Weslake single-cylinder motors, so, with Weslake struggling financially, NRE took over the four-valve speedway single and the eight-valve twin, which was used in, among others, John Hobbs’ famous drag racer, The Hobbit. In 1979, NRE provided Triumph with a kit for the T140 engine from which Meriden developed its own version, seemingly (and maddeningly) managing to introduce problems which there hadn’t been with the Weslake/NRE offering.

Standard T140 crankcases were used for the TSS, but there was a new shorter, stiffer, beefier one-piece crankshaft, to cope with the higher rpm the right valve head allowed – it was reckoned the TSS would rev to an eye-watering 10,000rpm and beyond, with 7000rpm the standard limit for a normal Triumph twin. There was a completely new aluminium cylinder block too, with its bores spaced half an inch further apart than the rest of the range, meaning the new connecting rods had to run slightly offset on the gudgeon pins at the small end.

The new result of this endeavour was an engine (now with flat-topped pistons owing to the cylinder head revisions) which made 59bhp, a not-to-be-sniffed at figure for a 750cc twin and one bhp up on the recently departed 828cc Norton Commando. But, sadly, shoddy manufacture meant that the first supplied examples of the new model suffered from porous cylinder head castings, and subsequent warranty claims pretty much strangled the TSS at birth, especially when allied to blowing cylinder head gaskets, as well as steel liners which slipped down the alloy barrels. It was all dispiriting and largely avoidable stuff, but instead of being the saviour, meant the TSS was just another nail in Triumph’s coffin.

In 1983, the last Triumph Bonneville left Meriden, as Triumph went into voluntary liquidation on August 26that year. In the wake of the collapse, house builder John Bloor bought the company, lock, stock and barrel, though lots of the spare parts and manufacturing plant went to Les Harris, who reached agreement to put the Triumph Bonneville back into production. The first machines were made in summer of 1985, with 1255 made before the licence agreement ran out in 1988, before Bloor’s Triumph, announced late in 1990, started production in 1991.

The new Bonneville arrived in 2001; of 790cc, its double overhead camshaft, eight-valve engine produced 61bhp, all showing that the men at Meriden weren’t far off the mark with their efforts, being what they had planned in the early 1980s.