Little seems to polarise motorcyclists’ opinions more than the following question – what’s the best configuration for a large bike engine?

Many older CMM readers will recall friends’ and relatives’

lives blighted by curmudgeonly heavyweight singles with more belligerence than

performance and a set of operational prerequisites that would make a diva

blush.

By the time last the British big singles rolled out of the

West Midlands they were the mechanical equivalent of Chris Farlowe’s classic

song and very unquestionably ‘out of touch and out of time’. Britain PLC had

had a gutful of what was euphemistically referred to as character. It would be

1976 before anyone felt brave enough to offer up an all-new half-litre

four-stroke single and Yamaha got it bang on the money with the XT500, creating

a whole new category of motorcycling in the process. Unfortunately the

subsequent road going single, the SR500, failed to find favour here in Blighty

even if it was an unquestioned success both in mainland Europe and Australia.

Yamaha’s competitors duly sat up, took notice and went away to do their

homework.

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

In the early 1980s a UK mainstream motorcycle magazine ran a

cartoon front cover with a latter day rocker astride a large Honda single along

with speech bubble coming out of his mouth saying ‘Nice and torquey!’ Within

the pages was the inside line on what techno feasts Honda was supposedly

cooking up. Ceramic coatings, unusual engine configurations, a return to GP

racing and even strange-shaped pistons were all variously alluded to. And in

among the stories was a suggestion that Honda, the arch proponent

miniaturisation for its own sake and doyen of multiple cylinders, was looking

at big capacity singles. We’d already had the XL500 and were drooling to see

the latest take on the concept; this would arrive in the guise of the XBR500.

Here was what The Big Aitch saw as the future for the single lunger and yet

most of us simply failed to get it.

Based around a radial four valve cylinder (RFVC) head

previously first used on the 1984 XL250R and XL600R, the bike looked

stereotypically Honda and despite all the pre-launch hype was nothing

particularly special. Of course there is only so much anyone can do with a large

capacity single cylinder motor; by its very nature its abilities are very much

self-limited. In retrospect the bike was a damn fine shot on goal and arguably

better than Yamaha’s outgoing SR500. One hundred cubic centimetres down on the

Iwata brand’s newly launched SRX600, the Honda’s star shone but briefly before

burning out to become something of a black hole.

Few in the UK were interested, which must have seemed like a

real slap in the face for Honda, but we Brits were obsessed with speed not

history. It might have seemed like game over but not for Honda. In a marketing

move that was as ironic as it was shrewd, the bike got a new suit of clothes

and was cheekily rebranded the GB500. All of the XBR’s 80s styling cues were

lost in one fell swoop to be replaced by a profile that could have been from

any UK factory circa 1952 to 1972. This new look was factory retro before the

idea had even been conceived; it was a commercialised café racer before the

Chennai Enfields were even oil-tight, a road going Manx for the masses even.

Hell’s teeth, Honda even went so far as to drop a TT Tourist Trophy logo on the

side panel… impudent damn Johnny foreigner or what?

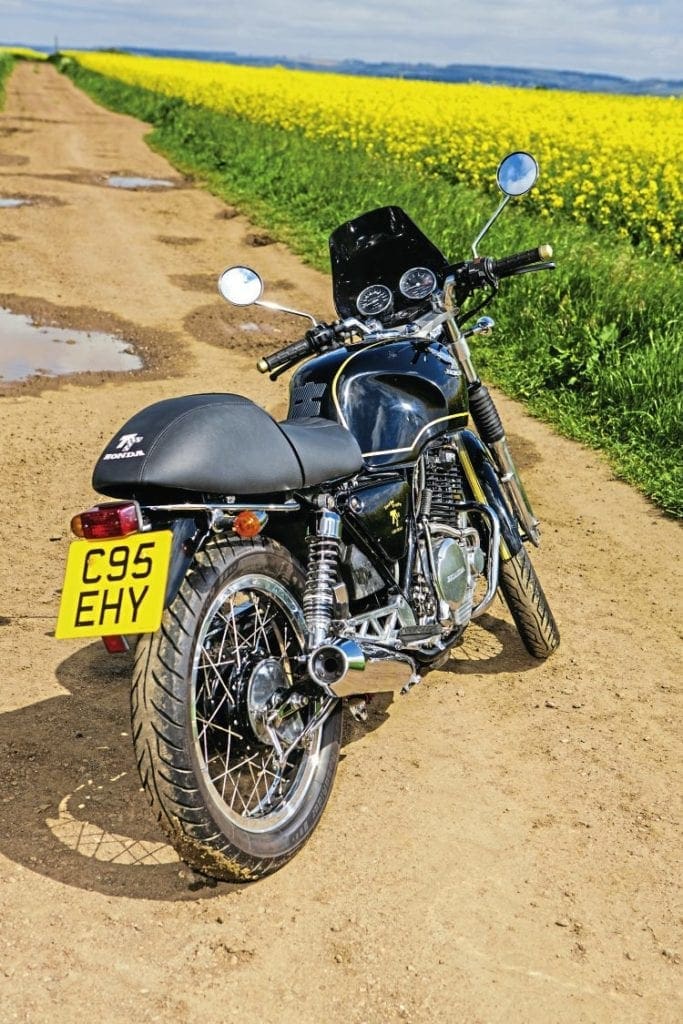

Perversely but predictably the GB500 was never officially imported here though numerous examples have latterly found their way back to their spiritual home and CMM has access to one courtesy of Kenny Howden. A previous owner has carried out a refresh of the bike, giving it a quasi Velocette look which suits it. In fact given the current trend for new retros it looks remarkably modern, if that makes sense?

All the key ingredients are there: humped single seat, gold

coach lines, polished alloy, satin black detailing and flanged alloy rims. That

list alone reads almost like a 60s rocker’s spec list but of course everything

is pure Japanese and its heart is dry sump motor – unlike anything sold to the

British public back when singles ruled the roads. Four valves sit within the

head, all angled towards a centre point with the sole purpose of facilitating

the best possible breathing for a single. This in itself is a serious

performance advantage, yet something not necessarily easily achieved.

In a perfect world the spark plug would be slap bang in the centre of the head but its ideal position is occupied by the single overhead cam shaft so the plug lives at the front between the two exhaust valves. The engine’s design team would doubtless have loved to go for double overhead cams but someone in charge of funding decreed this was a step too far. Shame really as it would have delivered the very best technical layout for a single.

Starting is either by kick or electric foot; the former on

the right and the latter on the left where Honda’s design team have even taken

the opportunity to add an alloy cover which imparts a subliminal period look.

Keeping that theme running on the right are a pair of braided steel oil lines

which again shout 50s special. With a wet sump motor there’d be no need for

such ostentatious plumbing and arguably on a dry sump motor such as this their

visual impact could have been minimised but of course Honda is once again

peddling retro here.

The XBR’s two-into-two silencer has been binned in favour of

a single reverse cone megaphone chrome unit which once again looks very period.

The fact that it has an outlet to atmosphere larger than a drinking straw suggests it might even make a decent sound as well. Completing the café racer tick box are a pair of flanged alloy DID wheels rims which look the part with that all important deeper profile supposedly necessary to keep the wheels of a super-fast sports bike true under power.

Today’s test ride is through the winding roads of North Lincolnshire and I cannot think of better roads for the GB. Jumping into that custom covered single seat it immediately feels right and the material used gives just the right amount of grip. The footpegs are moderately high and rear set but not uncomfortably so.

The seat foam compresses just a little to feel even more comfortable. The set-up is sporty without being cramped. Eagle-eyed readers will have spotted the bars aren’t standard GB500 issue; owner Kevin has swapped the originals for a pair of higher CBX550 bars for comfort. They work nicely too but, from a personal viewpoint, I’d like to sample the originals and see if I could get on with them. The engine starts on the button without a moment’s hesitation and the RFVC head rustles away pleasantly to itself. Just like Yamaha’s pioneering XT500 there are none of the rattles, clattering or chirping sounds you associate with the top-end of British singles. Considered design rather than financial compromises makes for quiet motors.

With the super light clutch in and the reverse gear lever tapped down into first we’re off and rapidly picking up speed. The acceleration isn’t manic and I’m confident my air-cooled RD350 would happily keep up with the GB but the way it makes power is impressive. I have to continually remind myself that this is a big single and not a multi-pot UJM. Okay, for some this might suggest the bike is over sanitised or homogenised but do you really want to feel white finger-inducing vibration through the bars, blurred vision or the prospect of peripheral parts falling off?

As history has shown, the reality of high performance singles was hugely different from the myths woven around them. Big singles fell out of favour for good reason. The balancer system used by Honda on the motor is amazingly effective and from a rider’s perspective makes the task in hand oh so much easier. You still get those solid dollops of power and torque but without the wearisome, fatigue-inducing, strength-sapping, vibes.

Within reason any engine speed, any gear, will do but work

the motor towards the upper reaches of the tacho and it simply revels at the

task. Big singles that like to rev are truly peachy! Carburation for a single

(and an old bike) is pretty damn good; the only foible was an occasional

almost-dying moment when the bike was fetched up from speed to a dead stop but

apparently… they all do that sir! To summarise the GB’s engine – if this bike

had rolled out of a UK factory circa 1969 we might very well never had seen the

implosion of our own, original, motorcycle industry.

Handling-wise it’s hard to fault the bike. Its narrow cross section is a real asset through bends within the limits of its retro twin-shock rear-end and simple forks never caused a moment’s concern. As it stands the GB’s weight balance seems perfectly positioned, giving the bike the feeling of not so much being steered or piloted through bends as thought through them.

They do exactly what’s asked of them without being lacklustre or aggressive: brakes that suit the bike and the style of riding it’s designed for. It’s genuinely hard to find anything significant to criticise about the GB500 and for an older machine that’s some achievement. Some might suggest the GB500 is a diluted version of the original rorty single but when the supposedly real thing failed to sell what options were there? In a classic world full of UJMs, screaming strokers and modern day would-be retro classics the Honda GB500 offers fun, thumper pros without the cons at an attractive price. What’s not to like?

There’s more! Want to find out more about the Honda XBR500? Then you can get your hands on the issue it features in! Just click here.