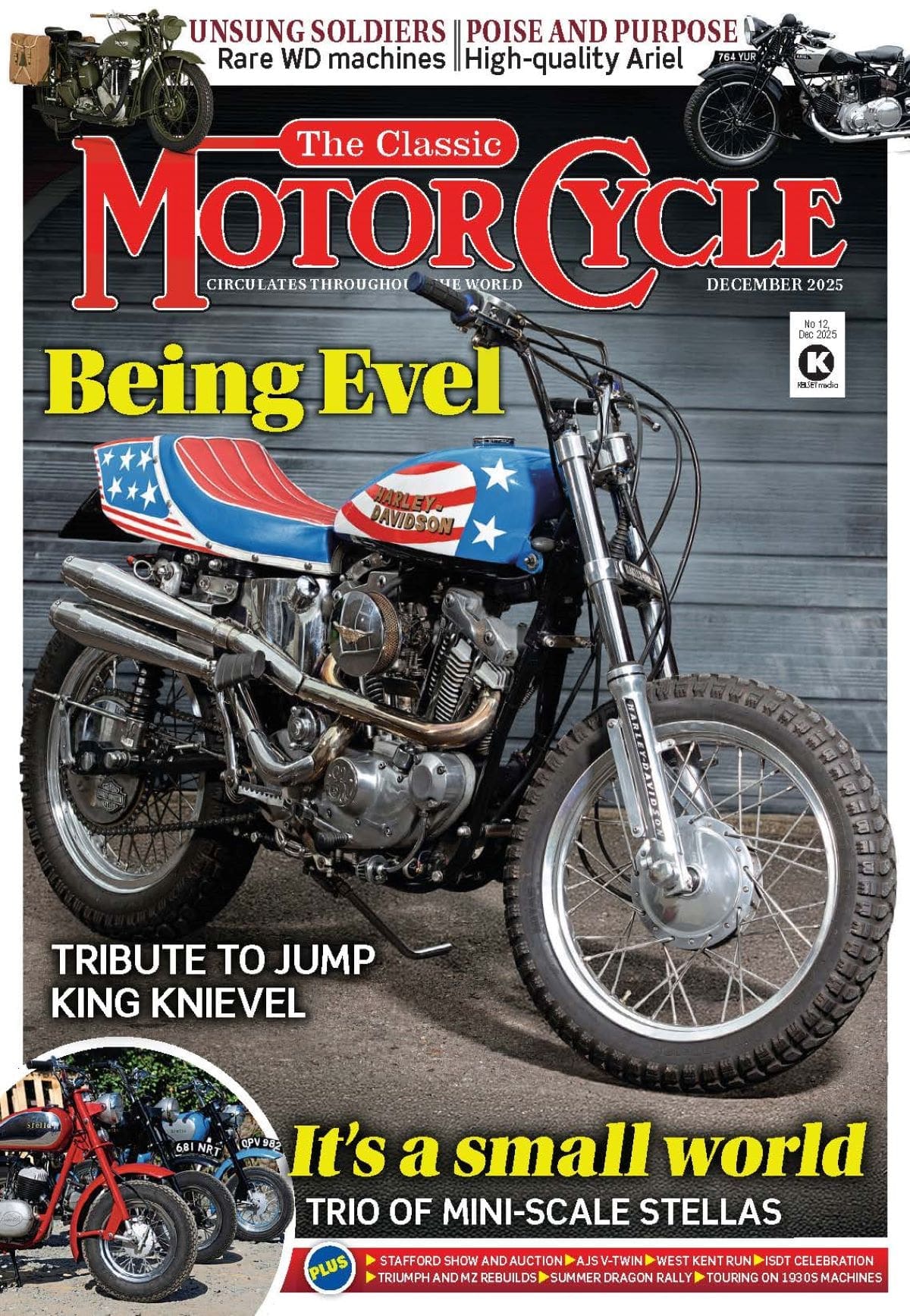

This well turned out Velocette Venom was possessed of the lightest clutch imaginable.

Words: JAMES ROBINSON Photographs: GARY CHAPMAN

Of all the motorcycles I’ve ridden, I suspect that Velocettes are potentially the most sampled brand. This has come about because of various factors, starting from parental influence, in that my dad has rarely been without one since he started motorcycling in the late 1950s, through geography and friendship; and having bought my own first Velocette when living in Lincolnshire, I was sort of adopted by several people for whom Velocette was almost a religion, a maker on a higher plain and without equal.

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

Many of these people were generous enough to let me sample their machines too, so, with regards to Velocette four-stroke singles, I reckon I have ridden pretty much most of them, through MOVs and MACs and Model Ks, Vipers, Venom, Thruxtons, KSS, MSS, KTS and – arguably most memorably – KTTs, pretty sure in every iterations, from Mk.I to VIII, though the nearest I have come to riding a Mk.VII KTT was a replica, but with only 37 built, that’s not too hard to rationalise. Of all of those Velos this one, pictured before you, had the lightest clutch of the lot. It was, quite simply, staggeringly light.

The Velocette clutch – a thing of apparent mystery, much head scratching, frustration, bewilderment and frequent bemusement (though try understanding the clutch(es) on a Vincent twin, it makes the Velocette seem oh-so-simple…), but, when set up and working like this one, my goodness, it really is incredible.

I’d not say that the one here is just the lightest Velo clutch I’ve ever pulled in, but, quite possibly, the lightest motorcycle clutch I’ve ever experienced. It was that remarkable. And this was on a big, hairy 500cc single, the most brutal, back-to-basics motorcycle of them all, if a Velocette can ever be described as brutal and basic. The feeling of this clutch is the absolute opposite of that; one doesn’t need to be He-Man with bulging forearms to operate it; a sickly one-fingered child with the strength of a malnourished kitten wouldn’t have any bother whatsoever. Said typical juvenile’s lack of patience would probably preclude starting it mind, but that’s a different factor, which we’ll address later.

And so back to the clutch. It works thus. While most clutches are operated by a single thrust rod, the Velocette uses a thrust cup carrying a thrust bearing (originally ball bearings in a cage, but now roller version is available) and three thrust pins against the adjustable clutch spring holder. It pivots in a gate-like hinged manner, being actioned by a large thrust pin itself moved by a bell crank within the gearbox shell. As the thrust cup is tilted it puts pressure on the clutch thrust pins which separate the clutch plates. What is unusual is that the thrust cup tilts, rather than being pushed square.

For the clutch to be fully disengaged, the plates have to complete one revolution, after which the self-aligning thrust bearing seating itself in the thrust cup levels the plates and frees them from the friction plates.

The other peculiarity is setting up the clutch, done using a peg which engages with the spring carrier in front of the clutch. Turning the rear wheel affords adjustment; there’s slightly more to it than that, but in essence that is how the clutch is adjusted. Meanwhile, cable adjusters are kept out of the way, so adjustment isn’t done on the cable. Again, the clutch must be set exactly as per the maker’s instruction. Anything else and it won’t work. Simple.

But why are some of them so light? And they really are – my dad reckons of one he had: “It was so light I’d sometimes worry that the wind would pull the lever in,” and he was only half-joking. The only things we can come up with are the logical explanations, so perhaps a brand-new, well-lubricated cable, lots of brand-new components (dad’s point of reference is his first Venom, bought new by his brother and by dad from him when it was a few months old) all moving free and easy, and lastly the clutch springs. The Velocette clutch as fitted to most of the later singles has 16 springs in it (though the Thruxton has 20 as standard, it’s reckoned they won’t slip with 16 in) and is of seven and nine plates. Reducing the number of springs would lighten it too – there’s certainly no need for as many as with some of the lower powered models. Perhaps different materials, bindings, tensions, all make a difference too, while there are varying length springs as well. All these things will have an impact and the culmination is how the clutch behaves.

The use of friction in clutches has always intrigued me. It seems counter intuitive, in so much as they rely upon friction being maintained for drive to be enabled. Surely, intuition would say that the opposite would be better, so that as material wears and friction reduces, there is no let-up in propulsion?

Early motorcycle clutches were reported before 1900 – Felix Millet being one who had identified a need – but Mabon (of North Finchley, London) was probably the first, or at least best known, early advocate. Marketed as a ‘free engine pulley and clutch’ the device was mounted on the end of the crankshaft and was operated by a cable from the handlebar. Introduced in 1906, it was metal-to-metal and was available to be fitted to ‘most standard machines’ and it must have been revolutionary, although perhaps these days we are less understanding of traffic conditions then – while a clutch would have been useful, traffic would have been so much less, and riders wouldn’t have been stopping so much.

By the First World War, gears and clutches were of course commonplace, such was the take up, while other systems (such as Rudge’s Multigear and Zenith’s Gradua, among others) gradually fell from favour, as a uniform idea of clutch and gearbox was adopted. All worked largely on the same principle, albeit with minor tweaks. AJS, for example, relied upon one central spring and just a single plate, which sufficed into the 1920s. Sunbeam decided that ‘clutch stops’ were a necessity, to halt spinning plates, although no one else seemed to.

In the meantime, the Hall Green, Birmingham, manufacturer Veloce was quietly getting on with establishing itself, under the controlling Goodman (formerly Gutgemann) family. The first motorcycle (a direct drive 400cc four-stroke single) had been made in 1905, then a five-year hiatus, before a 276cc four-stroke single, with two-speed gear in unit and driving through separate cone-type clutches. While advanced, it wasn’t a success and so, in 1910, Veloce did what loads of other nascent manufacturers were doing (hello BSA) and had a good look at the Triumph single – and basically copied it, producing the company’s opening 499cc four-stoke single. It was to be the first in an (albeit broken) line that stretched to 1971.

For from the end of the unit single until the mid-1920s launch of the 350cc overhead camshaft Model K, Veloce preoccupied itself with smaller capacity two-strokes, some direct drive, other early examples used a version of the two-speed gear and separate clutches, while a three-speed gearbox came in the early 1920s. The first Model K had the same gearbox and single-plate clutch as the range-leading two-strokes, which relied on a scissor-action quick-thread worm operation for the clutch, but in short order Velocette had adopted its multi-plate (three initially) system with pivoted clutch operation via the gearbox push-rod – and never saw any reason to change it. The same design literally served for evermore.

The other regular Velocette criticism is ‘they’re hard to start.’ That’s not strictly true, as they require a lot less physical effort than many contemporaries, but they are finicky to start, is probably the best way to describe it. A child arguably could start it – but would probably get bored of following the drill, which must be strictly adhered to for a positive outcome. If the starting drill isn’t followed, to the letter, every time, all that happens is… nothing happens, apart from the would-be rider gets increasingly frustrated. But the only thing to do is ‘trust the process’ and follow it. The way the kick-start is means just thrashing at it is not going to get a good result. The process goes thus – with petrol on and carb tickled, pull in valve lifter and give a few swings of the kick-start. Release valve lifter and find compression with the kick-start. Then, allow the kick-start to return back to the top, before pulling in the valve lifter, and pushing the kick-start all the way to the bottom. Release valve lifter and kick, all the way through. The thing is that if it doesn’t go first kick, then the whole sequence must be done again. This becomes increasingly hard as onlookers start to mumble about ‘bloody Velocettes’ and the kicker gets more frantic. Curiously, I have found it is often easier to start someone else’s Velocette, than your own. Reminds me of when we boys, my brother and I, and dad would say of his Venom, jokingly, “When you can start it, you can have it.” My brother, who is given to methodically working things out, realised that it was all to do with technique. He literally now owns that Venom after dad was good to his word.

This Venom featured here dates to 1959 (the peak year for Venom production incidentally, with nearly 1000 produced of the 5721 in total, from late 1955 to 1970) and was sold new by King’s of Oxford, the dealership belonging to Stan Hailwood, father of Mike. It has its original logbook back to day one, while it was also treated to a replacement big end in 2022, plus stacks of other work, with lots of receipts from Velocette specialist Ralph Seymour.

Now, the day I was riding this black beauty (I quite like the unlined tank, I must admit) it was absolutely pinging hot, the worst day on earth, really, for a potentially recalcitrant 500cc single. This one hadn’t been started for a bit, while Peter Rosenthal (who has it for sale, having taken it in for a deal with a Norton twin. Have a look at www.petesbikes.co.uk or 01354 692423) left me to it, so we were going in blind. It also has the standard auto-advance unit – at least with manual advance one can over-advance it and, although one might get a belt back through the kick-start for one’s troubles, at least it proves there’s signs of life. This one, nothing for a few kicks, then it’d burst into life – I think, with reflection, to start with it was simply not getting enough fuel and as the day went on, though every now and then it’d seem to make a refusal… And then strike up.

I’m always minded of a hot summer some years ago, when my cousin Peter and brother Simon were both running Venoms. Every time they stopped, one or other would have a sulk when coming to restart, then normally fire up just as the other died. It became a standing joke.

Once we were up and running, as I say, this one is dominated by its clutch and its utter loveliness, though it was largely matched by the rest of the cycle, though I did feel it was ‘working a bit hard’ almost as it was under-geared, with an indicated 60mph, plus a little bit more, feeling a bit more stressed than I’d expect. Indeed, it reminded me of my brother’s Venom, which has a similar feeling, though the gearing is standard. While I was sure at the time this one (or Simon’s) didn’t have a slipping clutch, was it, perhaps, slipping the tiniest bit, thus accounting for its lightness. I still can’t decide. But most likely, this one felt like that as I’d just hopped off a DBD34, which, despite being a 500cc two-valve overhead valve pushrod single, is about as far removed as it’s possible to be from a Velocette Venom.

A Venom feels light, precise and ‘engineered,’ unlike the perhaps more agricultural contemporary single cylinder products of say BSA, Norton or AJS/Matchless. Or anything really. That’s not necessarily a criticism of the others, just an explanation of how different they feel. A Velo is just a bit more delicate feeling.

There’s a story a Lincolnshire friend would tell about Freddie Frith, 1949 road racing 350cc world champion on a Velocette, when he had his dealership in Grimsby. Supposedly, Frith would size up a potential customer and, often, recommend that ‘sir’s money would be better spent elsewhere’ pointing him towards the local Triumph or BSA dealer, as something in their manner wasn’t going to agree with the peculiarities of the Velocette. For some, they’re a way of life, a deviation from conformity, while for others, they’ll always be a bunch of solutions to problems that didn’t need to exist. But anyone who has ever experienced that clutch in use cannot fail to be impressed and potentially beguiled, idiosyncrasies and all.