Words: Richard Rosenthal | Photographs: Rosenthal Family archive/Mortons Archive

Dictionaries inform the sidecar is: ‘a jaunting-car; small car attached to the side of a motorcycle; kind of cocktail.’ We’ll forget jaunting-cars and cocktails, but how did the world arrive at the sidecar? And what came before?

How to carry a passenger?

Today, we motorcyclists may carry passengers on pillion seats or in sidecars, but for the first pioneer motorcyclists, no such existed.

Many early motorcycles were direct drive machines, powered by small, attached engines, which were often pedal started. They were devoid of a clutch or other free engine facility and the rider stopped the engine at each halt.

If a passenger was to be carried, that passenger would have had to mount after the machine was underway (with the engine started) and dismount on stopping, or the rider would have to pedal/bump/paddle start the motorcycle with the passenger aboard. Either scenario was hardly ideal.

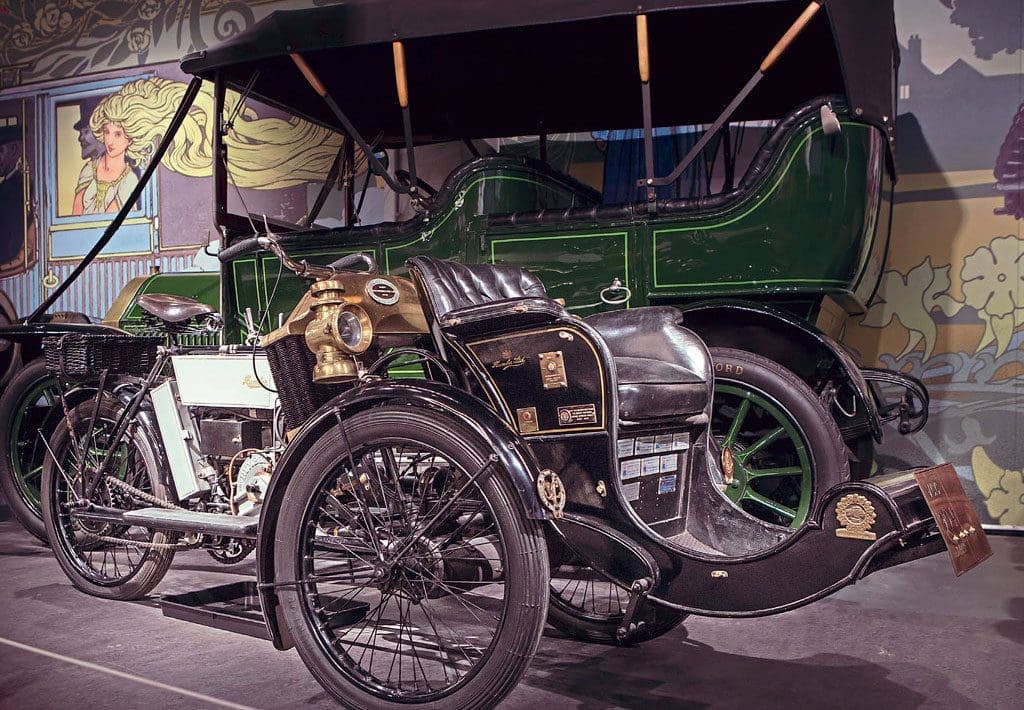

Even if carrying a passenger aboard the motorised cycle was viable, where to place their seat was the next question. Ideas included towing a passenger-carrying trailer behind a solo motorcycle (with some ambitious souls designing the trailer for two or more passengers), or to fit a forecar, comprising a seat mounted on a chassis between two wheels fitted to the motorcycle in place of the front fork.

The next development was the manufactured forecar, with its united chassis serving both the motorcycle part and the forecar.

Progressively, these became more sophisticated, but the desirability of carrying the passenger/s in front of drivers soon waned, in favour of sidecar outfits or cars.

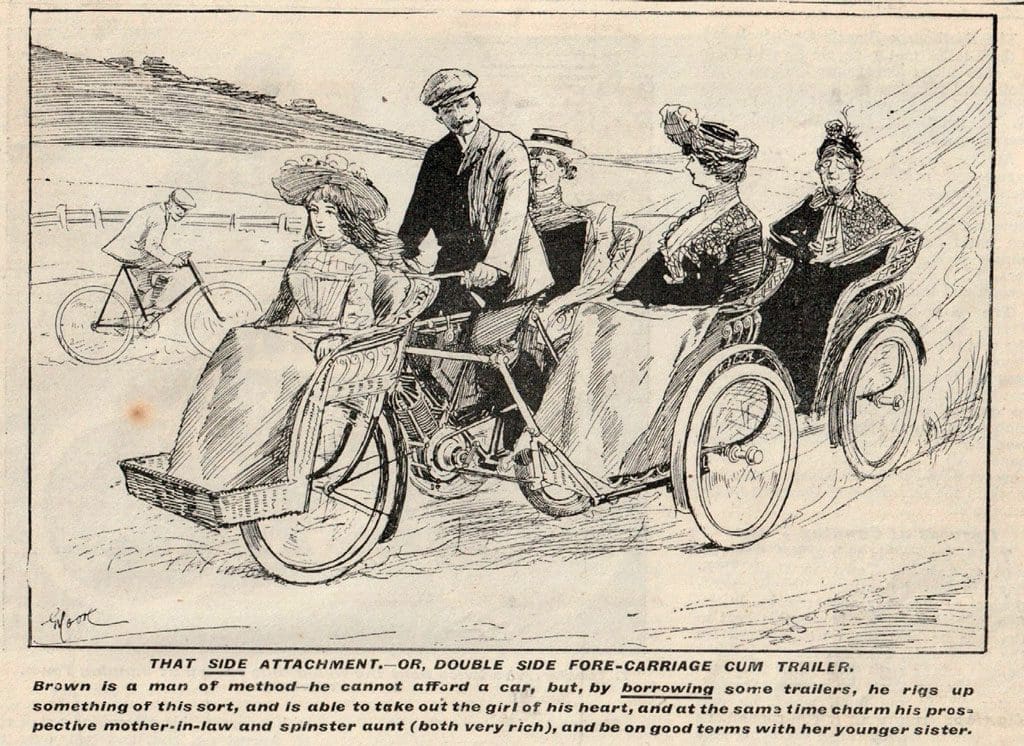

To us, it seems logical passengers travelling on solo motorcycles sit on a seat behind the rider, while sidecar outfits serve to carry goods or one or more passengers. But even by 1903 this solution wasn’t obvious, as the accompanying George Moore cartoon reveals (published: The Motor Cycle, January 7, 1903, page 413).

Moore’s sketch follows the rose-tinted thoughts of many in the period, in that the male motorcycle rider wanted to transport his lady love, but scanning the letters pages of the period motorcycling press uncovers a variety of reasons for passenger carrying – from transporting children to a West Country lady whose speciallybuilt tandem-type motorcycle enabled to her to visit nearby towns and further afield relatives accompanied by her blind passenger husband during the early Edwardian period.

Not all wanted to carry passengers and despised the thought, along the lines of ‘two people motorcycling together, halves the pleasure’. And whichever camp you fall into, the accompanying second George Moore cartoon (published: The Motor Cycle, August 5, 1903) will hopefully amuse.

Although I’ve looked at it many times, I’m still unsure which camp George Moore fell into at this time. Note: At the time, the term sidecar wasn’t in universal usage, rather many referred to them as ‘side attachments’ or ‘side trailers’.

Who was first to design a sidecar?

Some motorcycle history books say the first sidecars were produced in 1902 and a glance at the UK patent office records inform that in early 1903 W J Graham – of Graham Bros, Enfield – was issued with a provisional patent licence (Patent No1447/1903) for his sidecar chassis design.

The original Graham design was suitable for both cycle and motorcycle applications, but with its wheel/axle in direct line with the cycle’s/motorcycle’s rear wheel/axle, riders found it unstable, a situation soon improved by moving the sidecar wheel modestly forwards in relation of the cycle/motorcycle rear wheel. By how much was a debatable question, and still is, and is also dependent on the outfit’s intended use (road, racing, trials, scrambles etc).

However, despite lodging the first patent in the UK, Mr Graham wasn’t the first to develop a sidecar. This honour may go to French army officer Jean Bertoux in 1893.

The Bertoux design for cycle attachment comprised a tubular triangulated chassis with its single wheel set in alignment with the cycle’s rear wheel. The chassis carried a suspended sprung seat with back support and footboard.

A trailer for one, or two, or…

The concept of pulling trailers by some form of motive power – including horse drawn carts, on rails and by winches – was nothing new by the advent of ordinary (aka penny farthing) and later safety cycles. And a few even claimed to pull trailers with ordinary cycles, which takes some believing, but the development of the safety cycle made this viable.

The first example to hand of a motorcycle pulling a passenger trailer dates from 1898, and comprises a lightweight cycle-type passenger trailer coupled to a Werner motorcycle.

How the 1½hp four-stroke Werner (built in France by Russian emigre brothers Eugene and Michel Werner) managed to tow a passenger trailer along the flat, let alone up hills, was unreported, although if the rider applied lots of leg power it might have made forward progress and it is certain going downhill with nothing more than cycle brakes would be exciting… the machine comprised its engine fastened to a cycle frame steering head, with double lower front fork legs and twisted leather belt drive to a belt rim fixed to the front wheel’s spokes.

By the close of 1902, a few motorcycle makers, including Coventry-Eagle, offered passenger trailers for attachment to their motorcycles.

Imagining a lucrative market, cycle makers and engineering workshops – such as The Lacore Cycle & Motor Co and the H G Paine Cycle and Motor Works – developed their ideas of ideal passenger and commercial trailers as accessory items.

While some passenger trailers comprised little more than a small padded bench and footboard for comfort, others were luxuriously upholstered, with horse hair seats clad in leather, and the ultra-ambitious even contemplated trailers for more than one passenger, with the odd advert claiming, ‘…your governess could carry two or three of her charges in a passenger trailer.’

Motor tricycles such as the De Dion Bouton, Phébus, Beeston et al didn’t escape, as trailers were offered for these too. One could rightly imagine the advent of the sidecar put an end to the supply of passenger trailers, but a few makers continued to supply them primarily for cycle attachment, and of course a few motorcycling souls preferred the idea of a trailer rather than a sidecar, including Mr G Wakeman, who published his design in The Motor, June 24, 1903, page 466.

Mr Wakeman stated he built his trailer entirely from cycle components and included pedalling gear so his companion could assist when required… at the time of publication he was applying for patents and then hoped the device would go into manufacture.

Extolling his trailer’s virtues. Wakeman wrote: “It will no doubt be of interest to readers of The Motor, especially those who have 1½ and 2hp motors, who would like to have company on their rides. With this trailer one may help the motor up hills, and should the motor refuse duty, the passenger may assist to propel it home.”

Pondering Werner and Mr Wakeman’s machines, with small engines, could lead one to thoughts of the smallest machine to tow a passenger trailer – small box trailers don’t count!

Liking the bizarre, here’s my offering – a 118cc 1hp Wall Autowheel fitted to a tradesman’s cycle with large butcher’s boy basket ready for the road.

A few small post-First World War scooters have also been pictured with passenger trailers. If you can better these, we’d be delighted to hear from you.

Why a forecar?

Forecar attachments for motorcycles evolved, rather than were designed by a specific designer or company, and while some concepts were patented, the idea of placing the passenger between two wheels in front the rider dates to pre-motorcycle cycling days.

Although a few considered carrying passengers on or towing passenger trailers with ordinaries, the idea isn’t practical, as the rider has to run with the machine to get it rolling, climb the spine and sit before locating the pedals.

Having ridden a few ordinaries, one can’t imagine getting going while negotiating a passenger trailer for example without mishap and pain… but some makers (including Rudge) adapted the ordinary cycle theme to create racing and roadster convertibles for two people.

Such machines often had a central frame supported on small wheels front and back, with two large wheels, one each side of one of the two riders. In some cases, half of the machine could be removed to create a tricycle of sorts, comprising the original machine’s central frame supported on two small wheels and an ordinary wheel to one side, with the rider sitting between the central frame and large wheel.

Largely, these concepts were abandoned within a few years of the launch of safety cycles like the John Starley designed Rover safety, unveiled in 1884. Tricycles with two rear wheels based on the safety cycle-type soon followed and these were developed for two and even three people.

Taking just one example of the machines on offer, ex Humber employees Thomas Marriott and Fred Cooper established their wholesale cycle business in 1885, selling many machines built to Humber designs for them by Rudge, some sold by agreement as the Humber although, soon, Humber itself marketed its own cycles as ‘The Genuine Humber’.

In 1888, Marriott and Cooper displayed their Olympia Tandem, a three-wheeler with the passenger sat on a saddle in front of the steering head and between the two front wheels.

In most instances, the front passenger was kitted with pedalling gear, but steering and braking was controlled by the rider, sitting higher and behind the passenger. Soon, these were raced with success – for example Selwyn Edge (driver) and JEL Bates in front set a 100 mile road record in five hours, 30 minutes during 1890.

Designs along similar lines were followed by others and found favour with early car makers, including the well-respected Léon Bollée voiturette. Commercially launched in 1895, it was a 3hp single cylinder tandem tricar with the passenger sat between the front wheels with the driver seated behind.

In the UK, Ariel, Century (TCM, April 1989, pages 26-30) and others were in late Victorian days among the first to build voiturettes with the passenger sitting between a pair of front wheels and ahead of the driver. And in the four-wheeled car world, a few small light cars carried their passenger ahead of the driver.

This concept wasn’t the preserve of two-seaters, because vehicles such as the De Dion Bouton Vis-à-Vis carried its two front seat passengers ahead of the driver and another passenger, and as their name implies, the front seat passengers faced the driver and third passenger, making motoring in a Vis-à-Vis a social occasion.

Interesting as all this is, what use is it to pioneer motorcyclists who wanted to carry a passenger? After the 1895 launch of the De Dion Bouton tricycle, thoughts of passenger travel surfaced for this and rival machines.

Railway engineer Ernst Chenard, of Asnièressur- Seine, is credited as the first to adapt a motor tricycle to carry a passenger, by mounting a seat with footboard above the front wheel, making the tricycle more unstable. He next used a ‘convertible design’ whereby a two-wheeled forecar replaced the front forks and wheel of the tricycle, making for a more stable vehicle.

Although others pursued this idea too, Chenard is credited with making a few tricycles and forecar attachments with his future partner, mining engineer Henri Walcker. Circa 1899/1900 they started building Chenard-Walcker cars.

As well as making quadricycles, makers including De Dion Bouton listed detachable forecars, often known as convertibles or convertible tricycles. These allowed riders to remove the front wheel and forks of their motor tricycle and replace with a forecar attachment.

Rigidity was achieved by a pair of through rails (tubes) which fastened to the rigid rear part of the tricycle, while a girder-like component, or the machine’s original front fork (less wheel, mudguards and odds), link to the forecar attachment’s steering arrangement.

It was only a small step (circa 1901/2) for a few makers and riders to adapt the convertible quadricycle concept to suit the solo motorcycle. And soon makers vainly eyed up a lucrative market for such, including Mills and Fulford, Coventry, who went into production with the ‘Millford Hanson’.

An early advert – first used in late 1902 and into 1903 – led with: “That motor bicycle of yours can be turned into a LIGHT CAR in a few minutes.” Mills and Fulford not only built the Millford Hanson, but also offered a passenger carrying trailer and dipped a toe in the sidecar marketplace for the first time.

By 1905, they offered a castor wheel sidecar which initially wasn’t successful, but in 1910 patented (1409/1910) the ‘damped spring-loaded castor wheel’, which at least didn’t wobble like its first attempt.

For three decades Mills and Fulford built quality sidecars, then in 1932 took over the motorcycle maker Rex- Acme. Unfortunately, this enterprise folded three years later.

Apart from being a sizeable exporter of sidecars, as well as a leading supplier on the home market, Mills and Fulford devised a delightful trademark of a young lady fording a stream near a windmill and incorporated its brand Millford.

The thought of being able to convert one’s weekday transport solo motorcycle into a forecar to take a companion out on weekend jaunts appealed to some, including Canon Basil Davies, who penned ‘The forecarriage and how to drive it’ (The Motor Cycle, Vol 3, No 69, June 3, 1903, page B3).

Canon Davies (who became Ixion, the famous columnist of The Motor Cycle) detailed not only how to drive it but also how to convert a bicycle (motorcycle) into a forecar.

The detachable forecar enjoyed a short life although makers of entire forecars or tricars, which weren’t convertible, continued to produce such for a decade or more in modest numbers. While the light car and cyclecar did for manufactured forecars, the sidecar did for the detachable forecar attachment.

Why a sidecar?

To mount a passenger carriage aside a motorcycle must have seemed as bizarre a thought as the forecar or passenger trailer in the early Edwardian days.

Although ahead of the motorcycle or tricycle and avoiding its engine’s smells, heat and gases, forecar passengers were exposed to the road dirt and dust kicked up by passing vehicles, horses and other road users and, even worse, they bore the brunt of any front end collision.

Those in trailers behind the vehicle fared even worse, as it wasn’t unknown for trailers to unhitch and as well as forecar hazards, passengers also ‘enjoyed’ the muck kicked up by their motive vehicle and were close to the engine to savour its smells and heat.

As mentioned earlier, Jean Bertoux is believed to be the first to develop a sidecar for cycles, but who was first with a motorcycle sidecar? The Graham Bros. patents of 1903 imply they were among the leaders in the field but, arguably, slightly earlier others makers – including Mills and Fulford – developed a dual purpose passenger-carrying vehicle for attachment to motorcycles and, in some cases, cycles.

These devices offered the option of being used as a passenger trailer or with one wheel removed as a primitive sidecar. What the Graham Bros’ patent of 1903 did was provide a chassis design with secure fitments to the machine, initially of three point design of a style we’d still recognise today.

Closing thought

While I learned to drive a sidecar outfit at all road speeds – and can corner with enthusiasm – decades ago for work requirements, I’ve never been a fan of the third wheel, although occasionally a spin out on my son’s nutley blue BSA A10 coupled to a Watsonian Ascot can put a smile on one’s face. But one advantage, other than keeping the passenger/s dry, is their stability on our rough Fen roads and in icy conditions.