The ISDT’s laudable aims of promoting standard machines were still largely adhered to in the early Sixties. Of course, some standard machines were inherently more suitable for the task.

Words: Tim Britton Media Ltd

Pics: Mortons Archive

Picture the scene, the editorial office of The MotorCycle in autumn 1961, a couple of weeks before the 36th International Six Days Trial, which would be held in Wales. In those far-off days before we had keyboards, computers, delete and over-write facilities the only sounds would be the clacking of typewriter keys as a feature was being written, its writer conscious of time constraints which accompany any weekly publication. Like journalists the world over, a finger on each hand would press the keys and all the crossing out would be done on the notepad to one side of the writer.

Then the quietness was disturbed by a strident bell of a telephone, no fancy ringtone in those days nor any caller ID to allow the choice of answering or not. The handset is lifted, the ringing stops and the voice speaks: “Good afternoon, The MotorCycle editorial office, Peter Fraser speaking.” A page is flipped over on the notepad as Peter answers, his pencil poised for action. Who could be calling and what gem of information could be offered for the cutting edge of motorcycle press? Peter listens as the caller introduces himself and returns the pleasantries with: “Hello Henry, what can I do for you?”

The caller, Henry Vale of Triumph’s service department, wondered if perhaps Peter would like a canter on the T100A prepared for John Giles to ride as part of the Trophy Team in the ISDT in a couple of weeks? Naturally the offer of trying out a works prepared machine isn’t to be sniffed at by any means and it is likely Peter would have assumed the offer was for after the prestigious event… but no, the offer was for right then, a few days before the biggest off-road event in the world. The little scenario just presented is obviously made up but could have happened in such a way, as the press and factories had a much closer relationship in those days and liked everyone to think they were best buddies and always dropping in for tea.

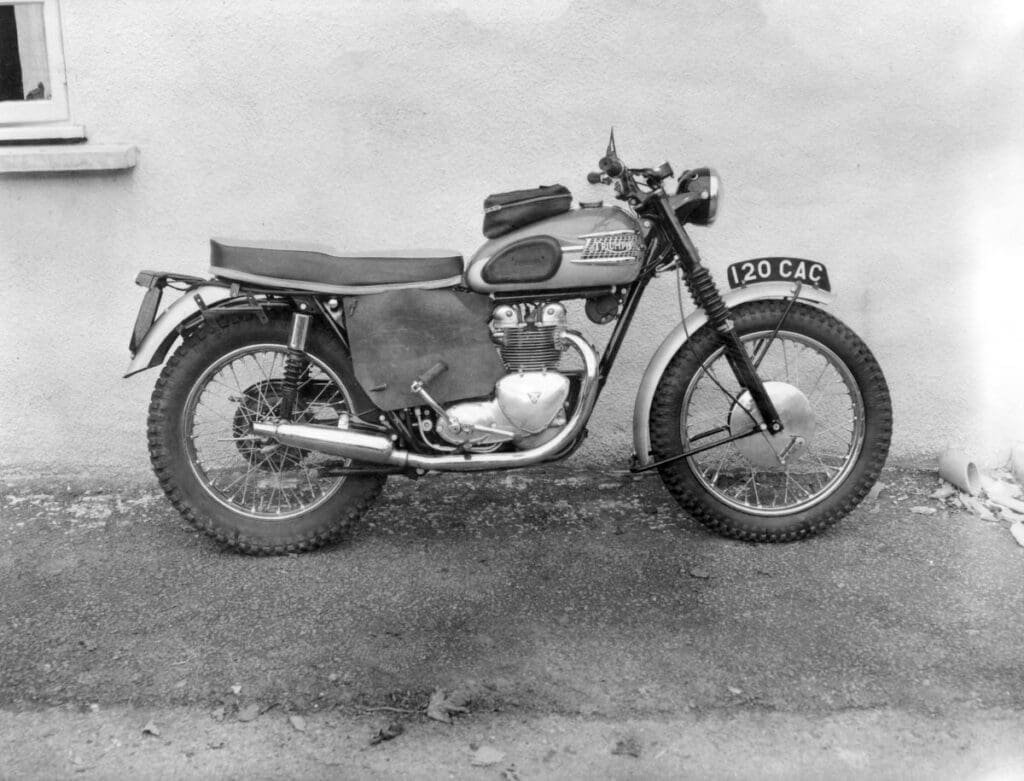

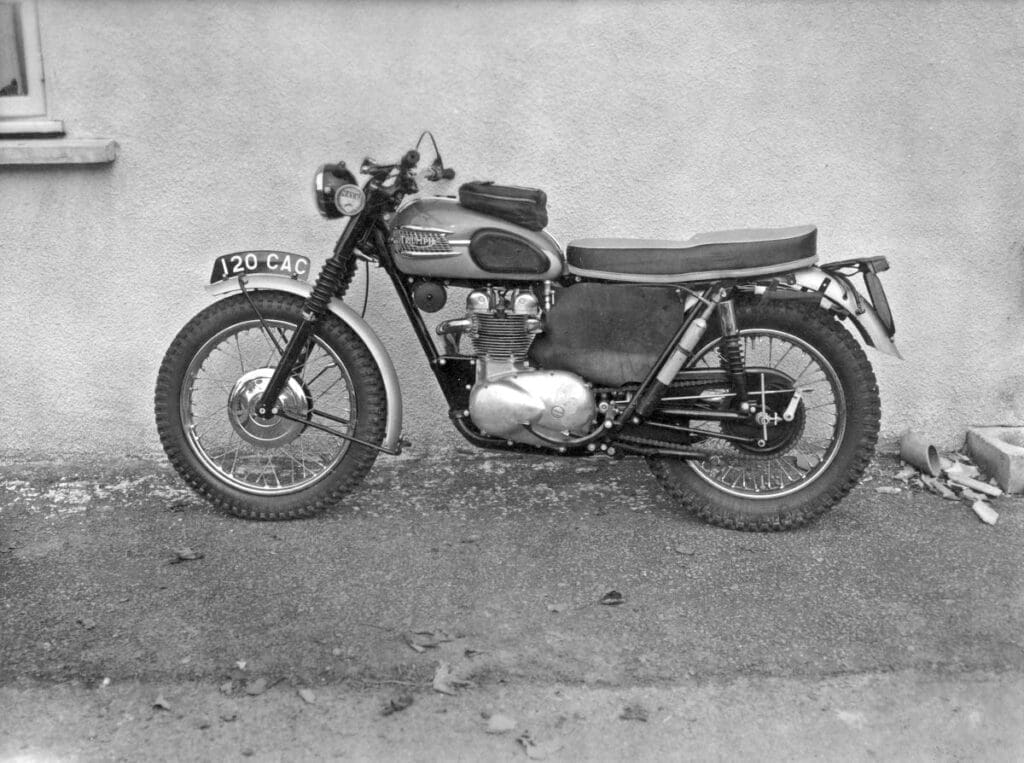

A quick check with the ACU to ascertain he wouldn’t interfere with route preparation by being in the area – and a call to book a room in the Metropole Hotel – and Mr Fraser headed for Triumph at Meriden to pick up the bike. In the early Sixties Triumph was still under the control of its mercurial chief Edward Turner, who was determined to civilise motorcycles and had the dream anyone purchasing one of his machines could ride it to the office in all weathers with only a city mac over their pinstripe suit and arrive clean. His thinking produced a rather tubby looking machine and, nice motorcycle though it is, in catalogue form it isn’t entirely suitable for hoofing over mountain tracks and along dirt roads.

Once at the Coventry factory Henry Vale gave Peter an insight into converting the ‘bowler hat and pinstripe suit’ demeanour of the sporting 500 in Triumph’s range into something leaner, more ‘Basil Heatley’ (Coventry born world cross country champ in 1961) than city gent and suitable for the 1200 miles of cross-country terrain it would come up against in the ISDT. Fraser learned the bike was one of three almost identical 500cc models also destined for the ISDT and while Giles’ mount would be used in the Trophy team, the other two would be ridden by Roy Peplow in the Vase A team and Gordon Blakeway in the Vase B squad.

Triumph’s ‘C’ range, begun in 1957 with the ’21,’ gradually replaced the older 500s until for 1961 in the UK there were three machines available – 3TA, 5TA and T100A – these were supplemented for the USA with the TR5A/R and TR5A/C. Strangely the TR5A model, already stripped and billed as an enduro machine, was a better starting point for ISDT conversion but wasn’t generally available in the UK. Was this the reason the home market T100A was chosen as the base, because the ISDT was to be in the UK? Who knows – but in reality there was little difference between any of the 500s once they were down to engine unit, frame, forks and wheel hubs. Perhaps the basic bikes were pulled from the production line before the bathtub and nacelle were deemed not powerful enough for the coming event so the 650 model’s front wheel with its 8in brake was used, though still with a 19in rim. At the rear, because of the bathtub weather protection’s location, Triumph fitted its qd rear hub in any case but modified it slightly with the spacer and chain adjuster as one bit so there was less chance of the distance piece being lost. To speed up wheel removal, in case of a puncture for instance, the rear wheel nuts had Tommy bars on them but removing the front wheel still needed a 5/16in spanner. Fraser was assured the engine inside was the standard T100A unit but it is likely to have been well put together, which is comp-shop speak for ‘gone through with a fine-tooth comb’. In fact there were only two modifications to the engine, the first a lowering of the overall gear ratios so the rider could trickle along in almost one-day trials fashion where needed yet cracking open the throttle would launch the bike to a top speed in excess of 70mph while the top two ratios could still be used on the rough.

The second was adding a spoke to the clutch action so the cable could be changed without removing the end case. A small fitting screwed to the end of the spoke as it poked through the hole in the case and the cable nipple slid into the fitting. This modification was deemed important enough to be adopted by the following year’s production range. There were also a few specific ISDT dodges included, the compressed gas tyre inflator and a cutaway throttle so the cable could be changed without tools if it was damaged and a tank-top bag instead of grid were seen on Triumphs at most such events. The rest of the ancillary components such as seat, fuel and oil tanks and foot controls were as T100A parts book. Henry Vale stressed the idea was to lightly modify and adhere to the standardish ethos rather than produce a super-special ISDT mount. It is possible the bike would be a few pounds lighter than the roadster’s quoted 350lb if only for the removal of the weather protection though.

Determined to mimic the starting procedures for competitors in the ISDT Peter wheeled the Triumph to the courtyard of the Metropole Hotel and with his photographer standing in for a time-keeper/starter he did as many competitors would do: a glance at the official starter, an impassive nod received and a determined prod on the kick-start lever brought the Triumph to life.

It might be wondered why this was a part of even a faux-test such as this one but in previous years had the bike not started in the minute allowed, a Gold Medal would have been impossible. For 1961 this had been removed from the regs and replaced with 20 debit points for starting failure which could impact on the team. Had it been the ISDT and were Peter an entrant he would have snicked into gear and roared off on the first day’s route; instead he spent a few moments warming the engine up as the photographer climbed into the car then the pair set off into the Welsh countryside. Peter’s first impressions for the Triumph were good: the controls fell naturally to hand and foot, requiring minimum effort to operate and their operation was smooth. Hustling through the gears was a joy, with each cog selecting perfectly and proving Vale’s thoughts on overall ratios to be spot on. Also coming in for praise was the handling with the suspension giving a good overall feel to the way the bike could be pressed through the bends on main roads and never felt in danger of breaking away when Peter took to the unmetalled tracks of the forest. Though observation and losing marks for footing is not a part of the ISDT, Peter did try out the low-speed one-day trials capability in a few muddy slots and found the bike responded well to such feet-up type of terrain and allowed this would be useful if the rider came across a section where riders were bunched up. At the other end of the scale, when tackling speed and special tests, acceleration and braking were prime assets and this T100A was lacking in neither area.

As he was summing up his report on what he called his ‘One Day International Trial’, Peter pointed out a few more dodges to ensure success in the world’s toughest trial. To maintain chain life a breather vented oil mist on to the rear chain and to protect against damage from the terrain there were substantial bash guards protecting the underside of the engine and its cases.

Giles, he mused, was going to have a lot of fun and satisfaction from this motorcycle in the ISDT as well as likely doing well.

we reckon it is Phil Irving listening to what John Giles has to say. Team manager Jim Alves is almost hidden behind the chap in the flat cap on the left.

John Giles

Hampshire agricultural engineer John Giles entered the off-road sporting world in 1946 mounted on a BSA Blue Star but will be forever associated with the Triumph brand.

He was drafted into the Trophy team in 1952 for the Austrian event and without any real knowledge of the ISDT set off to do his bit. Fast forward 10 years and by 1961 John was an experienced ISDT competitor and almost guaranteed to do well in the trial.

So it proved in the Welsh event as John once again picked up a gold medal on this T100A, no doubt aided by his one-day trials and scrambling experience. For those who witnessed his performance in the special tests, words such as ‘superb’ and ‘mastery’ were used to describe it. It wasn’t an easy event by any means and sadly for the British effort it was a bit of a disaster, though not for Triumph as all three – Giles, Peplow and Blakeway – picked up gold medals. Giles’ week started well with a maximum 60 bonus points picked up in the first day’s speed test. Day two’s shale hill climb saw Giles’ MX experience to the fore and he was rapid over terrain which saw many riders spinning out of control and dropping their machines. Like many others John would fall foul of the chaos at a speed test bottleneck which took the organisers and FIM jury a long time to sort out but in the end it was dealt with and he would have time to swap a rear tyre before handing his bike in to the Parc Ferme. Remarkably there were no other incidents worth noting for John Giles as he continued to the end of the event with few problems, unlike his Trophy team mates, and as he rolled into the finish on day six another gold medal was heading to his trophy cabinet.

Sadly during the writing of this feature we learned of John Giles’ passing; while it isn’t meant to be a tribute to one of the true gentlemen in our sport the description and tenacity of his competition combined with the willingness to help others is as fitting a tribute to the legend as could be put.