They were the answer to the dreams of a generation and, like so many good things, were banned. We bring you a guide to the Yamaha RD250 and 350 LC.

Words by Matt, his garish 1980s boots and ancient AGV Photos by Maria Hull

A huge thanks to Matt at MJMClassicmotorcycles.co.uk

The super sports 250 was a fabled beast in 1960s and 1970s Britain. Until 1961, learner riders were able to ride bikes of any size as long as there were L-plates attached, but a combination of teenage deaths and the arrival of the Rocker as a folk devil put paid to that.

One of the first sports 250s targeted at young riders in the early 1960s was the Royal Enfield Continental 250 GT, a back-breakingly uncomfortable lightweight with a genuine 85mph top speed. From then on, it was a race to the magic ton for the manufacturers. The first bike to claim a 100mph-plus top speed for a 250 roadster was the Aermacchi Ala D’Oro, an incredibly light, 24bhp four-stroke single. More of a production racer with lights than sensible road bike, Aermacchi claimed a top speed of 105mph for its Ala D’Oro. It was far too expensive for British teenagers on apprentice pay, however. Ducati’s Mach 1, another small production road-legal racer, was also rumoured to crack 100mph, but again was far too expensive for a working stiff. Japan entered the fray in 1967, in the USA at least, with Kawasaki advertising its Samurai 250 as being capable of 100mph, but this claim was probably hyperbole. In the early 1970s, Yamaha’s RD250, the first model with the round tank, saw riders rather than the manufacturer claim 100mph, but this was mostly fanciful pub bragging combined with optimistic speedometers. Suzuki’s GT 250 was also rapid, but less refined than the Yamaha offerings. The Kawasaki KH250 triple looked like it should crack a ton but couldn’t. The coffin tank version of the RD250 didn’t see Yamaha make such claims; the RD was a much more useable bike than its predecessors.

In 1978, Suzuki took the plunge, making definitive claims that its new GT250 X7 was a 100mph-plus model, a decision that came with unexpected consequences.

The Suzuki marketing ploy caused a lot of pearl-clutching and hand-wringing among politicians, and there were calls to curb this encouragement of teenage misbehaviour. Mopeds had already been restricted to 30mph and Labour MP for Stoke-on-Trent, Bob Cant, had campaigned for the ban on superbikes and other restrictions.

Action to cut learner bike speeds came from newly-elected Conservative transport minister Norman Fowler and his assistant, Peter Bottomley. They saw many a vote among the respectable blue rinse denizens of England’s market towns in curbing young tearaways from hurtling through market squares and down ring roads at night on 100mph strokers. Originally, the assumption in the motorcycling world was that learner riders would still be able to use 250s, but with a much-restricted power output, along with enduring new two-part motorcycle tests. It therefore came as a shock to all to hear that far more draconian restrictions were to be imposed, involving a huge reduction in the capacity and power of learner motorcycles to 125cc and 12bhp.

The tests arrived first, and the power restrictions came in early 1983. With their arrival, the excitement of being a young motorcyclist on L-plates lost a lot of its glamour, and motorcycling has never been the same since.

The RD250LC

Between 1980 and 1983, Yamaha gave the leather-jacketed youth one last fabulous swansong: the RD250LC, the fastest and best-loved of all 250cc learner motorcycles.

Yamaha launched the RD (race developed) 250LC (liquid-cooled) in November 1979 at the Tokyo motor show as the home market RZ250, and it was a sensation. Based, Yamaha claimed, on its all-conquering TZ and YZR racers, the 250LC and its liquid-cooling was a game changer in both 250 and 350cc models.

Believe it or not, some of the original styling concept was done by underemployed staff at struggling British company NVT (Norton Villiers Triumph), who were employed by Yamaha Europe in the Netherlands to come up with some concepts, the designers believing at the time that the new LC was to be a 125. John Mockett, cartoonist for Motor Cycle News, designed the italic wheels.

The all-new liquid cooled, piston-ported, reed valve engine was at the heart of the new bike. It had two barrels rather than the single castings of the TZ and produced an impressive 36bhp at 8500rpm. The bigger 350, which came out a few weeks later to fulfil the enormous pre-order list it had gathered, produced 47bhp.

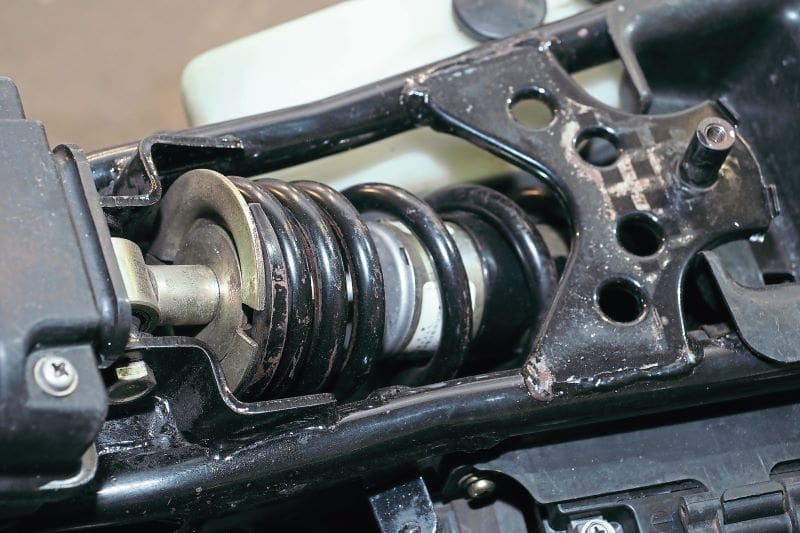

Despite the addition of the radiator, the powertrain was impressively light. There was a six-speed gearbox. The frame, too, was revolutionary. It used a monoshock swingarm similar in concept to the Monocross design Yamaha was using on its trail bikes but with a shorter shock absorber running under the petrol tank, the monoshock being something of a small bike first. The compact duplex cradle frame managed to be both stiff and lightweight. Extremely light italic cast wheels and much use of plastics for casings and bodywork kept the weight way down. There were some radical up-to-the-minute stylistic innovations, too. For years, small bikes – and indeed, bikes generally – had been dripping in chrome. On the LC, the engine was all-black as Yamaha two-strokes had been in the past, but so were the expansion chamber styling of the exhaust pipes and the headlight, instruments, indicators and mirrors, with the only shine appearing on the headlight rim, grab rail, wheel rims, forks and the alloy footrest hangers. Colours were restrained; it came in white with blue or red stripes or black with white, red and orange flashes. To keep the price of the 250 down to a level distinguishing it from the near-identical 350LC, there was a tiny amount of cheeseparing. There was a single front disc and a drum rear, unlike the 350 which got a twin front disc set-up. So, master cylinders were also different, and the 250 got one horn instead of two. There were some differences in the final drive sprocket arrangement, the 250 having two more teeth and a different cush drive arrangement. It had kick-start-only starting, and a simple prod was all that was needed to get it alive.

Riders soon found it was possible to fit 350 barrels and pistons to a 250… doing this while retaining your 250 side panel badges and not telling the DVLA or your insurance company was very naughty indeed and hardly ever happened, honest.

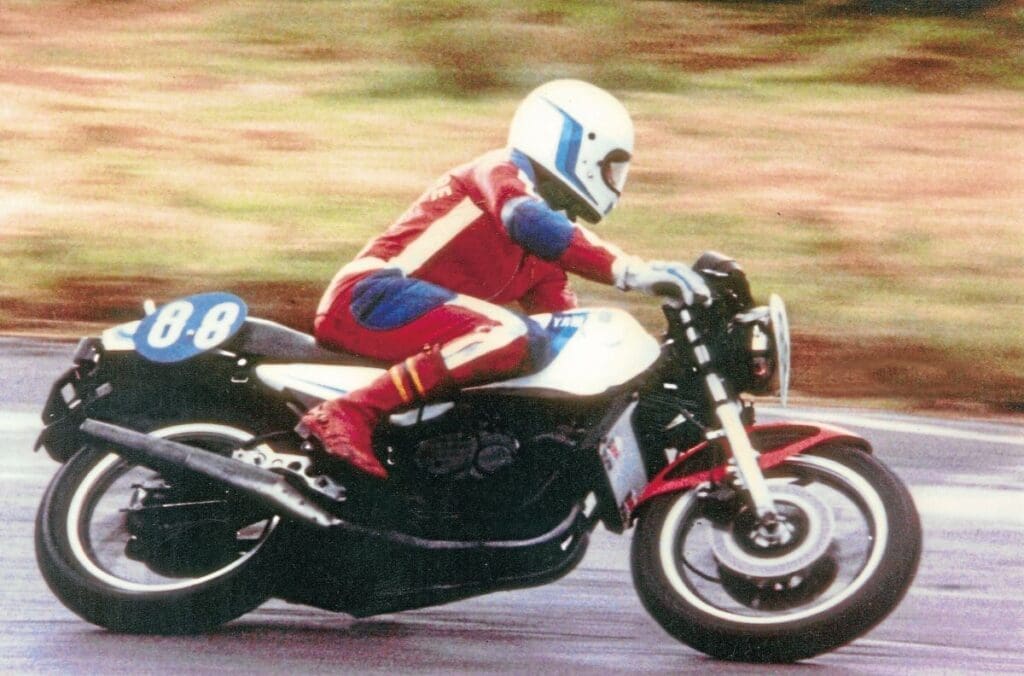

At £1030, the LC was the most expensive Japanese 250 on the market by as much as £200, but many a teenager did the maths, worked out that the annual HP payments weren’t that much more than for its rivals, and took the plunge. Interestingly, and possibly realising that baiting the lawmakers was a bad idea, Yamaha claimed a top speed of only 98mph. In fact, the LC could reach 105mph untuned, and in the hands of a skilled tuner could go much faster than that. It was so fast that it dominated racing entries, as a well set-up LC could challenge racing TZ250s when in the hands of a talented and fearless rider. It also became one of the most stolen bikes of all time, sometimes to supply more unscrupulous would-be racing superstars.

Buying an LC

Getting your hands on a good LC today isn’t hard but requires deep pockets, a forensic attention to detail and a careful eye. Premiums are paid for original equipment such as exhausts and more obscure bits such as under seat tool trays, original heat-welded seat covers and grab rails that were often discarded back in the day. An original 1980 LC will be white with blue or red decals stuck on or in the black ‘Mars Bar’ colour scheme, which is marginally less popular, but some people love it, so it makes little difference to the value. The most important things to look out for are the frame and engine numbers. If it is UK spec, they should match and should have 4L1 as a prefix. If it says 4L0, that means there are 350LC bits involved. Barrels on a 250 should also be marked 4L1 somewhere. If originality is your thing, you want the single disc and the smaller brake master cylinder. If not, having two discs from the 350 is a good thing. Original exhausts are also different on the 250 and 350 and marked appropriately.

Matt from two-stroke expert BDK Race Engineering likes the RD engine and agrees with a standard, but a set-up engine is best for reliability. “But watch out for oil pumps, as the 250 oil pump is shimmed differently to the 350, so be careful if you’re buying a used one or have a 250 that was converted.”

Parts

Yambits can provide a huge number of parts for a 250LC off the shelf and has commissioned petrol tanks (made in Taiwan) and can supply the sought-after plastic tool tray and brake hose clamps. While many parts such as rubber mounting grommets, cables, wiring looms and clock surrounds have been remanufactured, it is important to get parts made of the right materials. Karl, from Yambits, said: “We have looked at getting side panels made, but it’s very difficult to get the right grade of plastic to do it properly. We are getting a batch of seats made up later this year.”

Other bits, like carburettor bodies, are out of production and hard to come by, but all the internals are available and can be fitted to restored bodies. Some parts are hard to find. Stators, for example, are best sorted from specialist suppliers. Karl says that often people try to buy items like stators without checking that this is where the problem is and are disappointed that the issue isn’t solved. Matt, of MJM Classic Motorcycles, said: “Many rear mudguards were cut down and numberplate holders junked, and so are fetching stiff money second-hand. The rear shelf under the tail unit was often cut up to shove the rear light further under and the little tray behind the fuel tank is often missing, as is the black plastic coil cover you see poking out from the front of the tank. Airboxes are £180 if you find one and oil tanks are more than £150 second-hand.”

Big selling items are general service parts and air filters, but also clutch parts. “Yamaha never supplied clutch parts,” said Karl “You had to buy the whole assembly and supply all the bits to fit your basket, including the Teflon gasket and the rivets.” Crankshaft assemblies are also popular; Yambits ship them out to Japan for LC fanatics there.

Imports

Many bikes have been imported to the UK from Germany, where the LC was as popular as it was in the UK. These came in two versions: a lower-powered 27bhp restricted version with 4L2 engine numbers and a full chat 36bhp 4L1 version. The restrictions were different carb internals and a baffle in the centre part of the exhaust. Both these issues can be resolved fairly easily. The supply of German bikes has largely dried up now, but they do still appear. EU bikes will come with KPH clocks, and finding MPH clocks will be a challenge and can be £500 if they do appear, but replacement clock faces are available and work well.

Also, restricted German bikes will have a much less hectic life with the lack of power, so gearbox bearings and bottom ends have had it easier and often make a great basis for a restoration. A good straight and original UK-market RD250LC will cost between £8000 and £10,000. Expect to pay £4000-plus for a complete project bike. Modified bikes are often cheaper too, as restoring to stock trim is the goal for many nowadays.

Oli meets Elsie: A brief, youthful dalliance

My first experience of riding an LC came in mid-1983. One of the mechanics who worked at the garage where I was a pump attendant had just blown up his CB900R and picked up an LC for next to nothing, the bottom having dropped out of the market for 250s thanks to the new 125 laws.

I had an XJ650, and there had been mutterings about swapping, so we swapped keys. Tucked in on an LC, with my head down over the ‘bars, the machine felt like nothing on earth. There was no vibration, and you could barely feel the tarmac beneath you. It flipped round corners intuitively, with next to no effort, the wind whistling past your helmet and the crackle of a two-stroke at full chat in your ears. Just recently I had seen the Star Wars movie Return of the Jedi. If you’ve ever seen it, you might recall a sequence in which the baddies race through a forest on a small flying motorcycle called a speeder. It’s one of the film’s more exciting sequences – and that is what riding an LC is like. It flies along, with not a care in the world.

It’s a complete rocket of a motorcycle: joyous, hilarious, life-affirming, fast without being dangerous, and crazy without being insane… and so much more rapid than my lumbering 650 shaftie.

I got back to the garage and when the mechanic got back on my XJ650, he just gave me my keys back and said: “Nah.” I don’t blame him for a minute.

What are they like to work on?

Matt Marsham has been restoring LCs for decades and has kindly given us the heads-up on a few trinkets.

Firstly, Matt says imports aren’t an issue, but you need to know if a bike is, or isn’t, from Europe. Euro bikes mainly come from the German market and can be restricted, or not. They have a rivetted-on chassis plate, while UK bikes just had a chassis number stamped. The exhaust usually has a restrictor welded in about a third of the way into the silencer, though some European bikes were not restricted. This just looks like a giant washer which stops them revving and can be removed but take your time so the expansion chambers don’t look butchered.

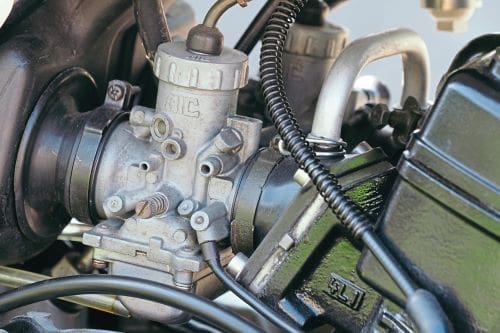

Carbs are said to be different, but Matt doesn’t see any differences to the bodies and just changes the jetting to suit an unrestricted bike. Standard carb bodies are really hard to find now but are the key to a reliable engine.

A German bike can be a good thing, as with only 25-odd horsepower and the restriction through holding back the revs, the bikes have had an easier life than most UK machines! Gearboxes, cylinder bores and bottom ends will benefit.

If you’ve stripped the bike, after painting the frame, pop the swingarm in and then get the rear shock in – top eye in first, then the bottom eye – otherwise, it’ll never fit! Likewise, get the two-piece standard airbox (another great but expensive part for keeping a bike reliable) in early or you’ll not get it in.

Clutches are no issue, and you can get repair rubbers and rivets for the cush drive to cure the rattling often encountered. And brake discs can be skimmed as they are quite thick.

The drab green finish on bolts, indicator stalks, the rear brake lever and other parts is a plating that is only allowed by those with military contracts who insist on £100 minimum orders, which is fair. But Matt has a couple of as-new parts he’s used to mix up a 2k paint finish which is hard enough to protect and looks just as good. How far do you go?!

What are they like to ride? From Matt, an LC newbie

I’ve read all about them, been staggered by the cost of one, bored to death by RD ‘experts’ and am a firm believer in ‘never meet your heroes’ – but I’d never ridden a liquid-cooled Yamaha RD and had to scratch that ding-ding-ding itch. They were around 10 years before my time, so it was Kawasaki’s KR1, the Suzuki RGV250 and later the Aprilia RS250 for me. Therefore, when serial restorer Matt Marsham, of MJM Classic Motorcycles, offered me a go on a freshly finished 250 example, I crossed his palm with two-stroke and was most eager to see what all the fuss was about.

Jump on and the RD250LC doesn’t feel small. It feels like a ‘real bike’, not a learner machine. That is until you lift it upright to pop the sidestand up. Then, all the perceived weight just disappears, and you’re left with the safe, reassuring feeling of a 125. You can imagine how those learners felt when they dropped a leg over an LC at a show or at the local Yamaha dealer. It would have felt completely possible to be an owner: “How much per month, did you say?”

Everything is familiar to a modern motorcyclist; gears on the left and first is down, ignition key in front of you with idiot lights, a disc brake (or two if you’re on a 350), and lights that work. You even have indicators and mirrors. Only the choke plays hide and seek for a second, and you quickly find it on the left-hand carb. Oh, and the seat needs a clip on each side to take off to get to the secret storage under the seat. I cannot remember and don’t want to remember what a 17-year-old would have wanted to hide under there…

Compared to the British single I ride, you merely blow on the kick-start – it feels like you’ve no compression to a four-stroker, which I suppose you haven’t. Choke if its cold, and it cools down quickly, but pop it in after a few seconds to save the plugs from fouling. Two-strokes are best warmed up by riding, gently-ish, according to Matt, who rebuilt this motor. It has fresh rings, big and little ends on a low-mileage bike, so I don’t wish to ruin his hard work.

You have to rev them to pull away. Repeat this until it’s firmly embedded in your grey matter. It’s not a sound that travels too far, like the bass of a four-stroke, so don’t worry about the noise – and you’re 17 again, so who cares what people think? Second is smooth and flexible around town, and as the bike warms nicely, you can travel in traffic without sounding like you’re on the grid at Donington.

The lightness adds ease to riding and is enhanced by the nice-to-use switchgear, mirrors that actually show you what’s behind, and a riding position that is much more relaxed than it is racy. The original handlebars are a delight, though look odd, and the beautifully-covered seat looks great, but the original foam could be harder… but then I should be riding fast enough not to notice, so my fault. The brakes and forks work really well and are suited to each other; the forks feel responsive and comfy around the back lanes, with the single-disc front brake with rubber hose giving lots of feel and enough braking for the lightweight bike – too much would just have the tyres letting go. I imagine that riding an RD faster would have you fitting twin discs from the 350 and possibly firmer springs and reducing the air gap in the forks. The rear brake is a drum and nice and strong – in fact, it’s locking up the rear you have to be careful of, not worrying about performance.

The well-behaved forks match that TZ-inspired rear shock. With so little weight to control, it’s got an easy life, and with a skinny 3.50×18 rear tyre and 3.00×18 front, you don’t even need steering – shift the weight on your bum cheeks and you’ve moved your position or even your direction. It’s cornering by thought.

Gears. They get visited a lot, once you start to have fun. And changing up and down the ‘box is fun. You are any one of the 1980s GP riders you wish to emulate and have a soundtrack to match. It feels unnatural at first, with years of four-strokes making us lazy, so it ends up being a pleasant change… something to think about, like riding a hand-change prewar bike if you’re not used to it.

I don’t know about consumption, nor do I care. I assume this is a Sunday ride for anyone who wants an RD, and the tap has reserve, so don’t worry. Make sure the oil tank is full with something good from a well-known make and use super unleaded, maybe even with an additive.

Maria and I went briefly two-up, and I even had a camera bag on – there’s plenty of room for chip runs or treating a mate to your memory lane machine. Steering lock, helmet lock and a small amount of storage is useful, but the lightness we love when handling also eases those putting it into a van. Lock your Elsie up or lose it.

I loved riding the LC but still couldn’t make the figures add up. Then, once the photos were done, I went out for a ride. Roads I know, corners I like, in a jacket and jeans. The cornering is brilliant; because the bike’s lightweight, the suspension doesn’t need to be amazing. Good Avon Road rider tyres give confidence and aid with braking, and you can be changing gears, chasing the redline and feeling like a racer, but you’re not actually doing mental speeds. And when you hit town, you sit comfortably upright, just as you can out the other side in the 1960s again. Except you’re on an LC, so it’s head on the tank, chasing your mates.

I wondered why you’d spend such a lot of money on a 250. Didn’t make sense – until I rode it. It’s fun, fairly easy to restore, looks fab, doesn’t take up a lot of room, goes as fast as you want and, crucially, makes you feel like you’re 20 again. No amount of money can make that happen for real. If you’re 50-something, I may have found you the elixir of life.

SPECIFICATION:

ENGINE: 247cc reed valve induction two-stroke twin BORE/STROKE: 54mm x 54mm COMPRESSION RATIO: 6.2:1 POWER: 36bhp @ 8500rpm IGNITION: CDI TRANSMISSION: Six-speed SUSPENSION: Telescopic front fork, cantilever monoshock rear BRAKES: Single 10.5in disc front; 6in SLS drum rear TYRES: Front 3.00 x 18; rear 3.50 x 18 WHEELBASE: 1360mm/55in SEAT HEIGHT: 31in WEIGHT: 305lb (dry) FUEL CAPACITY: 16.5 litres FUEL CONSUMPTION: 40mpg TOP SPEED: 98mph

SPECIALISTS:

Yambits: yambits.co.uk

OWNERS’ CLUB

The LC Club: www.lcclub.co.uk

Been waiting for this ride for more than 30 years and it didn’t disappoint. Jump on and just ride, enjoy the two-stroke workout, and take yourself back to a time long gone