BSA B25 was a 247cc, unit single-cylinder bike, produced between 1967 and 1972. An evolution of the C15, and with roots harking back to the Triumph Tiger Cub, it held the British flag for the growing teenage market. And it can give a lot of fun today, too.

Words by Oli Hulme Photos by James Archibald

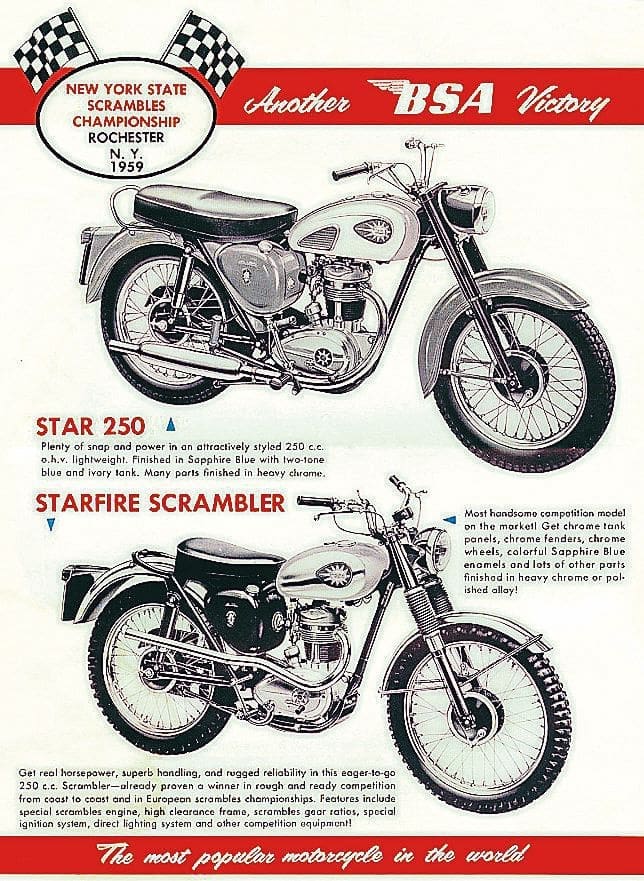

In late 1969, Bob Grant, from the Triumph importer on the US West Coast, had an issue with a dealership in Memphis, Tennessee. The dealer had not ordered any Triumph TR25W Street Scramblers – a bike that was basically a BSA Starfire 250 with a high pipe and Triumph badges. The dealership was supposed to stock all the Triumph models they made.

Bob wrote: “Your experience with the TR25W is not unique. It has been a somewhat troublesome unit for everyone. However, it is a Triumph and that is what we sell. There are a lot of people who would agree with your comment that we should dump them in the ocean, but this would not be practical… In spite of some mechanical shortcomings, the TR25W is easy to sell and a lot of customers are very happy with them.”

Those mechanical shortcomings were replicated in the Starfire and well-known by 1969. These highly-strung, highly-tuned 250s had a not unwarranted reputation for exploding dramatically. The Starfire’s high-compression piston could make a badly set-up one hard to start, and UK owners were nearly always young and poor, with little money for preventative maintenance. They were thrashed – and thrashed hard, and this was the problem with the Starfire. BSA didn’t seem to realise how hard a teenager could hammer a motorcycle. In the UK at 17 years old, you could go and buy one of these snarling little cats on the never-never and thrash the guts out of it in all weathers. American youth too, would use them on and off-road, often with disastrous results. Hard riding, mixed with the minimal servicing, meant the engine suffered, the result being that some bottom ends and top ends did fail under the strain. Weekend thrashing meant some serious spanner work on Sunday night if you were going to get to work on Monday.

It was a fall from grace, as the BSA 247cc unit single had been the bike that helped kept Britain moving in the early 1960s. When BSA realised in the late 1950s that the Government was going to introduce laws limiting learners to 250cc machines, they knew they had to do something about the product range. Their 250 offering at the time was the C12, a heavy and pedestrian pre-unit single that was going to find itself competing for the business of thousands of learners with Royal Enfield’s sporty Crusader, Ariel’s revolutionary Arrow and Leader two-stroke twins, not to mention highly-strung but gorgeous Italian singles and some mysterious machines appearing in the Far East. Casting around for a solution, they decided on a redesign of sister company Triumph’s 200cc Tiger Cub, straightening the cylinder up and boosting the capacity to 250cc. Launched in 1958, the C15 Star was a softly-tuned commuter at first, but the arrival of the 250cc learner laws saw BSA get to work, making it more attractive to the youth market. The SS80 was the first road sports model, with a hotter engine and a claimed top speed of 80mph. There were poky off-road versions too, notably a model called the 250 Starfire.

Production of the C15 range continued until 1967, when the staid commuter and its mildly sporty stablemate and off-road cousins were replaced by the altogether flashier C25 Barracuda. This was all-new, with a stiffer frame and a much more powerful, big-fin engine producing a claimed 26bhp. This revved to 9000rpm, had a 10:1 compression ratio piston, and was fitted with a ‘supersports’ camshaft. There was a smart new fibreglass petrol tank, big, sculpted fibreglass side panels and a humped seat. The whole deal knocked spots off the look of the old C15 and appeared to be a worthy rival to the Japanese 250s then hitting the market.

The Barracuda had slender lines and used several parts from bigger bikes in the BSA range, which made it attractive to learners. The front forks were BSA’s own items and similar to those fitted to the company’s A-series twins. There was a big chrome Lucas headlight and an optimistic 120mph Smiths speedometer, Girling shocks at the back, a QD rear wheel and 12-volt electrics.

The Barracuda name lasted just a year before the bike was renamed the B25 Starfire. American car giant Plymouth owned the rights to the name, which sat proudly on a very sporty coupe.

The frame on the C25 and B25 was a strong affair, proving itself more than capable of handling the bigger B44 Victor 441cc engine. The front brake eventually went full width and the high-compression piston was retained, though BSA decided to drop the valve lifter that had made the C25 easier to start. When the UK Government banned fibreglass petrol tanks it was changed to steel and grew in size. In 1969, the Starfire got the excellent full-width 7in TLS (twin-leading shoe) front brake from bigger BSA and Triumph models, and rubber gaiters replaced the steel fork shrouds. The 1969/70 Starfire was about as good as it got for a British 250, with modifications to the engine breathing to help with oil retention at high revs. It did still fail, however, thanks in part to an inadequate con rod. BSA dropped the sculpted fibreglass side panels for an exposed oil tank and a smarter, smaller effort on the other side, which improved the lines. It was replaced in 1971 by the B25SS with slightly lower compression, a new con rod, conical brake hubs and an oil-in-frame design, and renamed the Gold Star 250 – to howls of rage from the traditionalists.

The B25S Street Scrambler

By 1969, BSA had got close to making the Starfire strong enough to take the strain. And for the US market, it took aim at youths and created a new model just for them – the B25S Starfire Street Scrambler.

It wasn’t a complicated conversion; it had already been selling a Street Scrambler model with a stock Starfire tank and a high-level pipe with a wire heat shield, but the 1970 model line got a brush-up from the parts bin. BSA replaced the wire heat shield with the glassfibre item from the Triumph TR25W, bolted on a couple of folding footrests, some high ‘western’ handlebars, and from the back of the stores, the tank from the utility model, the low-compression engine-equipped Fleetstar. The Street Scrambler was given a groovy candy blue paint scheme with a white stripe and a red pinstripe, aping the Union flag, which was only three years late for the swinging London craze. One assumes the chaps at Small Heath weren’t up-to-date with trends. The tank had the advantage of bearing some resemblance to the original Shooting Star Daytona item from the 1950s.

Hardly any Street Scrambler appears to have ended up in UK shops, though a UK-registered one was seen on the cover of a Shadows album, Shades of Rock.

This example

The B25S seen here had an uncertain birth. The engine and frame numbers don’t match, but they were made a few days apart, in October 1969. The bike doesn’t appear in the factory despatch books, either. It was registered in the US but arrived back in the UK in 2016 with knobbly tyres and was listed on the import documents as an off-road vehicle. There are a number of curious lugs brazed to the frame, and there are suggestions it might have been used as a stunt bike at a circus – the lugs being used to insert bars for performing tricks. There was a fire at some point in the past too, as seen by damage to the clutch cable casing; it lost its speedometer and that ghastly glass fibre exhaust heatshield. The petrol tank leaked, and the wrong side panel was attached to the left-hand side.

I know all this because it is mine. I bought it at the VMCC jumble at Shepton Mallet in 2017.

I fitted the right speedometer and drive, and found a replacement petrol tank from a Fleetstar, which I got repainted by Vince at Rusty Road. He was mortified when, at the first go, he produced a red pinstripe with a slightly uneven finish and I had to beg him not to repaint it. I showed him the original tank with a similar blobby factory finish. One imagines the original painters didn’t care as much as he did. Recreating candy blue was an issue, so it was matched with a metallic blue for a Vauxhall Corsa. I found the correct exhaust heat shield in Ireland, and that’s pretty much all I’ve done to it, cosmetically.

I had to change the cable to the front brake and I have replaced the gaiters twice. You can pull the top end off in half an hour and have the wheels off in similar short order. Lining up the front mudguard is a challenge, the electrics are basic 12-volt but work well.

I’ve subsequently found the original ‘for sale’ advert from 2016, which describes the engine as ‘noisy’ – which it definitely is. I’ve spent much time trying to work out what the noise is, and, after a top-end rebuild, and dutiful adherence to the Rupert Ratio valve clearance setting method, as well as careful application of my engineers’ stethoscope, and the simpler method of sticking my finger into the exhaust pipe and having it come out coated in sticky black 20-50 multigrade, I have come to the conclusion that the dreadful racket is piston slap. It certainly explains why the Starfire is so easy to start with its allegedly 10:1 piston.

It does run, however, and can put in a surprising turn of speed for an old girl. It handles very well on its ancient knobblies.

On the road, the Starfire is a huge amount of fun. It will turn heads on the high street, probably because of the racing dumper truck engine noise, and parking up will quickly find me approached by ladies and gentlemen of a certain age wanting to talk about it. They, or their long-gone teenage love interest, will have had one in the 1960s or 1970s.

This winter I’ll have the top end apart and get a new piston in there, though there is, of course, always the concern that some extra compression will have a disastrous effect on the crankshaft. However, it will, I hope, stop it smoking like the Torrey Canyon (for the young people reading this, the Torrey Canyon was an oil tanker that broke in half off the Scilly Isles in 1967. To deal with this, the RAF dropped incendiary bombs on the wreck).

I’ll get the oil tank and side panel repainted and the right transfers attached too, and put another summer under its wheels.

Should you buy a Starfire?

A Starfire is perfect for nipping to the shops, to the pub, or for blatting along deserted B roads to a bike night. You can jump on it and after giving the beast a couple of healthy prods, it will burst theatrically into life. The Starfire is just the thing to have sitting in the garage for when you feel like being a teenage hooligan again. They’re loud mechanically, partly because of the long pushrods from camshaft to cylinder head, the echo chamber of a rocker box, and the big, undamped aluminium fins. The valve clearance adjustment involving eccentric cams is a tricky process that, presumably, was thought to be a good idea at the time. The use of across the range BSA cycle parts makes them solid performers and makes keeping one going a breeze, as there are multiple parts suppliers. The front brake on the later models, from much bigger BSA and Triumph models, is superb. The clutch is sweet and the gearbox crunch free, and feels – modern. Once you get it into fourth gear and you roll back the throttle, be prepared for rapid progress, while keeping an eye on the oil pressure light and an ear open for unwelcome noises. They don’t even vibrate that much – for the rider, in any case. Things do fall off if they are not regularly checked though, as the engine’s buzziness will shake components loose. Despite their reputation for fragility, if you get one with a quiet bottom end and with decent filtration, a late 1960s Starfire will have you grinning from ear to ear. You could fit electronic ignition if you feel the need, but the points set-up can work well. It’s worth considering fitting a lower-compression Fleetstar piston if you can find one, or a compression-reducing bottom cylinder plate. After all, these days you are unlikely to be trying to keep up with a 650 Lightning or outrun a police Ford Zodiac.

The Starfire is a great, affordable introduction to classic British motorcycles and is fairly simple to work on, despite the curious mix of Whitworth, UNC, UNF and BA fasteners. They’re lightweight when compared to others, and the seat height is reasonable for most, too. If you fancy a different kind of old Brit and don’t need it for day-to-day transport, Starfires are cheap to buy and a good choice for a first British motorcycle. Picking up a good one for not much more than £2000 privately is by no mean impossible. You’ll see dealers asking £4000, but it seems certain that this is more out of hope than expectation.

Specification (1969 model)

ENGINE: Dry sump 249cc single ohv COMPRESSION RATIO: 10:1 BORE and STROKE: 67 x 70 POWER: 25bhp@ 8000rpm CARB: 28mm Amal Concentric PRIMARY DRIVE: Chain/wet multi-plate clutch, four-speed gearbox IGNITION: 12v coil and points WHEELS/TYRES: Front 3.25×18, rear 3.50×18 BRAKES: Front 7in full-width 2LS, rear 7in half-width QD FUEL TANK: 3.25-gallon/14.75-litre steel OIL CAPACITY: Four pints/2.3-litre SEAT HEIGHT: 31in/787mm, length 82in/2083mm WHEELBASE: 52in/1321mm GROUND CLEARANCE: 7in/180mm DRY WEIGHT: 302lb/137kg

Owners’ Club

BSA Owners’ Club

Specialists

BSA Unit Singles in the USA has a huge database of information and spares

UK Specialists

Burton Bike Bits

SRM

Draganfly