When making a bike for the learner market, the Japanese quickly worked out that emotion and desire was more important than technical innovation.

Words by Steve Cooper Photos by Gary Chapman

If you were a teenager of the 1970s and the sight of a Kawasaki triple doesn’t fire those recollective synapses, then you probably have a hole in your soul – it really is that simple. Even if two-strokes aren’t your thing, there’s no denying the visceral impact of the maddest bikes of the period. We can all dream about the chest-beating 750s and the trouser-compromising 500s, but for many the smaller 250/350/400 versions were more practical, viable and/or accessible. Be honest here, who hasn’t aspired to owning one? It’s a little like that line from the 1970s rock film That’ll Be The Day: ‘Show me a kid who didn’t want to be a rock star and I’ll show you a liar!’ Triples are most emphatically like that.

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

Almost without exception, the 250 is the most accessible in terms of both cost and availability. Yes, they may be the slowest of the genre (depends on the rider, Steve – the younger the rider, the more fearless they are – Matt) and the likes of a well-maintained RD250 will outpace and out-handle an S1-cum-KH250, but that misses the point entirely. The three-cylinder motor allied to that asymmetric tail end, further combined with the associated aural delights, were, are and will forever remain the bikes’ USP (unique selling point). Nothing quite sounds like the smallest triple when they are given the beans, which is how the manufacturer intended them to be ridden. Oh, and of course, those stunning, drop-dead gorgeous looks – Kawasaki’s stylists were always on the button when it came to sorting out a bike’s lines.

The ride and the bike in camera

Cards on the table time – although I don’t own one, I’ve become a huge fan of the smallest Kawasaki triple. Therefore, perhaps you’ll excuse me if I get a little over-enthusiastic? Quite simply, even in my dotage the attraction of that trio of small pistons has suckered me in like a teenager… Kawasaki’s three-pot lure is still working fine after all these years, then!

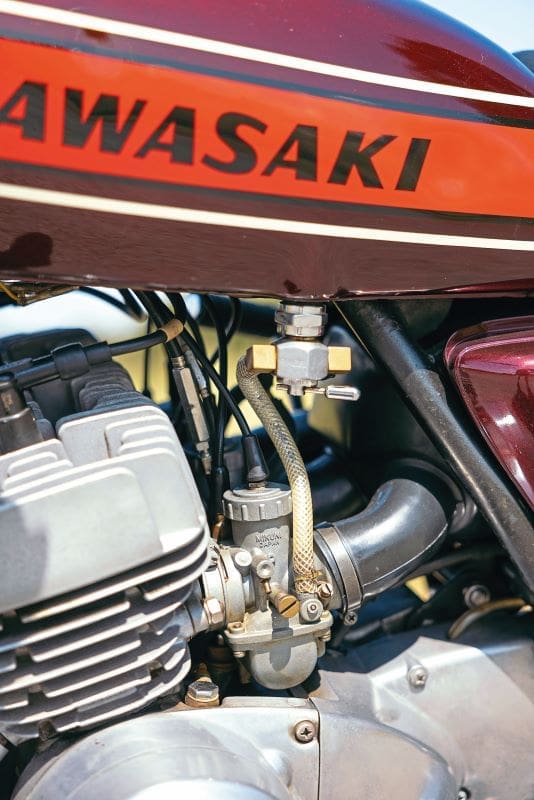

The fired-up little sounds like a baby triple and even more so on these non-standard Allspeed pipes – the sound is addictive. And just to spite the rivet counters out there, yes, these are the wrong colours for the S1B, but the owner likes his bike this way. Another deviation from OEM is the fitment of the alloy rims. Oh, and the missing rear guard? It’s not. This is an American market bike so they were never fitted as standard!

Our bike in camera is a well-used example with a delightfully ‘loose’ motor, which absolutely flies. It’s not rattling or tapping but everything has just bedded in to that sweet point that means it’s as sharp and effective as it can be. Aided and abetted by those exhausts, you’re egged on to wind open the taps and work the engine, which is never a chore, to be honest. Once the tacho needle gets to the magic 6000rpm mark, the bike takes off like a miniature missile.

It’s very possibly ungentlemanly to spout off about top speeds here, and especially given CBG’s demographic – surely we’re past that sort of thing now? Is the S1 the fastest 250? Does it really matter? Being a triple, it is carrying a little more mass and is slightly less aerodynamic, so that has to have an impact. The later KH250s are often said to be the slowest of the breed but I’d put the S1s up there or close to the contemporary Suzuki’s GT250 and a little behind the race-developed RDs. Argue all you like, basing your reasoning on data gleaned from period road tests, but know this – every press bike of the day had been breathed on or blueprinted. Therefore, those old magazine figures are about as accurate and relevant as your mate’s boasts!

Styling-wise, the S1B laid down a format that would roll on through to the KH iterations. The subtly squared-off tank of the S1 and S1A had been exchanged for a much more rounded version, and the black headlamp brackets of the older models became chrome. Look a little deeper and that cute tail piece – very much a Kawasaki thin – had changed contours too. Similarly, the gauges of the S1B were revised in looks and silhouette. In essence, the B model would help establish an outline that would last through to the late 1970s.

The bike’s road manners are of the period, for sure, but nothing like those of the wayward 500s and 750s. We’re not talking triple with a ripple here! In fact, the 250/350/400 chassis is generally acknowledged to be the best-handling of the family. This may go some way to explain why some fans shoehorn the half-litre motor into these smaller frames. That said, the S1B here came with the optional steering damper that was generally mandatory on the bigger bikes, so perhaps a previous owner looked upon its presence as some kind of insurance policy?

A good S1 can be hustled like any other 250 of the day but arguably with a little more aplomb and precision than, say, a contemporary Honda 250 twin. Having sampled most of the period quarter litre offerings, over the years I’d personally put our test bike up there or just above the Suzuki GT250 and only a little behind Yamaha’s RD. Brakes-wise, then Kawasaki lags behind, or is that actually surges ahead? The cable-operated rear brake is adequate and possibly okay but the front anchor leaves a little to be desired. By the time the S1B was on sale, Kawasaki had already realised the twin leading shoe drum that the S1 and S1A shared with the original 1972 S2 350 was borderline. The 1973 350 S2A had a disc brake and, rather obviously, the 250s really need it too! Why wasn’t one fitted until the introduction of the KH250? Costs saving, over-ordering of components, downright stupidity – it’s anyone’s guess. Ridden with a modicum of forethought, the S1’s front brake is fine and you’d get used to it but it was, and is, a little lacking compared to its peers. Nowadays, a wise rider might very well invest in some modern, softer linings and spend some time setting the unit up to deliver its best.

So, if Kawasaki’s S1 250s aren’t necessarily the best-handling, the fastest, or the best braked, why were they so popular then and remain in demand today? The answers are variously image, ego, kerb appeal, bragging rights and oh so much more. As a 17-year-old, you could have a two-stroke triple that looked and sounded like the 500s and 750s. Kawasaki was on the ball by applying a familial look and style to all of its triples and kept the lineage going when it changed paint schemes and decals year on year. You could be seen as being ‘guilty by association’ on a 250, which was some image to have as a callow youth. Those three pipes, that engine note, the styling – nothing came close for many. To steal a line from radio’s Emperor Roscoe, ‘Baby, if that don’t turn you on, then you ain’t got no switches!’ I rest my case.

Costs and options

Reality check time – the 250 Kawasaki triple is no longer cheap. Even if the bulk of the classic market is cooling down somewhat, the baby triple’s value has been enhanced by the aura of the 500 and 750. Most expensive of the smallest triples will always be the first year S1, which was only ever sold in small numbers in the UK due to a very sketchy dealer network. Of the S series, the C variant is the most common, closely followed by the B. If you were after an S series 250 rather than a KH, then quite possibly the S1A is worth tracking down. In European Gold with two subtle stripes, it looks very much like its rabid 750 H2A brother, which is no bad thing. The KH versions are more numerous but not necessarily cheaper than the later S models. Condition and build accuracy are more important than apparent mileage. It’s still possible to buy a project in boxes but we’d advise against; something is always missing and you generally need three of everything for the motor.

A complete S1A ripe for restoration is going to be about £3000 to £4000, with a restored example circa £5500 to £6500 depending on condition. Sellers are still asking £10k for a mint 1972 S1, but whether they get that is debatable. A rough but complete S1C recently went for £3100. The KH250 was more readily available when new and it would seem that nostalgia for the later 250/3 is still buoying up prices. An example with signs of use and patina but totally usable is going to be about £3500 to £4500, but at the upper end it really needs to have the airbox, OEM exhausts, etc. Dealer price for a ’79 B4 is going to be in the region of £5000 to £6000 at the time of writing.

Good news is the 250s are relatively well-supported by the specialists out there. Most of the pattern or aftermarket stuff is decent quality, although there have been some issues reported regarding cheapo pistons and rings. The likes of Z Power, Kawasaki Triple Parts and so on hold decent stocks, and what they don’t have they can normally get.

Faults and foibles

Trim parts, seats and gauges – the usual Japanese items – all need to be there and correct for the model. Kawasaki carried out regular revisions of the bike over its 10-year lifespan, so everything must be from the same model or very close. The Kawasaki Triples Club is the default for advice, specifications, and, very often, parts. The cognoscenti agree the smaller triples handle better than their bigger brothers, but a fork service and possibly upgraded shock absorbers is unlikely to go amiss on a machine of unknown provenance. The drum brakes are of their time and reward careful setting up. The KH250 discs are similar, and modern pad materials are worth investigating. If your reference points are period Suzuki or Honda, then you probably won’t be too disappointed with the 250’s anchors. However, if you’re coming from a Yamaha YDS7 or RD250, you may need some time to adjust to the Kawasaki’s brakes. There’s nothing inherently wrong with them, they’re just not exceptional.

Obvious but often overlooked is the fact that there’s more to service on the engine. An extra set of points to gap and time, and extra carb to set up and so on. Not a big issue but worth considering if you’re not regularly ‘on the tools’. Seizing centre pot horror stories abound, but almost all of them are myths and fantasies.

Overall, there’s not too much to worry about, but it’s always worth noting the following:

■ Lead balance weights pressed into the crank’s flywheels sometimes work loose, locking the motor solid.

■ Selector forks bend, leading to missed or baulked change and gear linkages wear.

■ Tinware, airboxes and rear tail units must be there.

■ Centrestands can seize on their mounts, leading to horrendous bodges.

■ Watch out for delaminating brake shoes and leaking front calipers/master cylinders.

■ Aftermarket electronic ignitions are common. Many a 250 has been robbed of its points for use on a 400.

Potted history

From a technical perspective, there is genuinely no reason whatsoever for the S and KH 250 to exist as they fundamentally do nothing better than their predecessors. In fact, most who know the brand well will tell you the previous A series Samurai twin was a better machine. Its disc valve motor was genuinely faster and its chassis had better manners. However, the baby triple was a substantial facet of marketing and brand image. Someone high up decided back in 1971 that all the road-going strokers would be triples and so that’s what happened.

The following year, 1972, saw the iconic S1 revealed, which was an instant headline grabber. The press bikes were white with green stripes and, allegedly, ‘massaged’ to crack the magic ton – the legend was born, as they say. From here onwards, the S1 gained a letter suffix A, B and C until 1976, when there was a major marketing rebrand. All two-stroke road bikes became KH (Kawasaki Highway), hence the change from S1C to KH250. Styling was generally dictated by the 500 and 750s lines, with the 250/400 following a similar visual set-up; only the colours and graphics/decals/badges being 250 specific.

When Kawasaki began its transition to four-strokes, it was the 750 and then the 500 that were dropped from the range. The 400 followed a little later but, perhaps surprisingly, the KH250 hung on much longer. Why? Two reasons. (A) There were rumours of the forthcoming 125cc learner law and (B) quite simply because the KH250 was still selling by the crate-load and it was effectively cheap(ish) to manufacture.

Whereas Suzuki and Yamaha felt compelled to update, reconfigure and eventually redesign their 250s, Kawasaki felt no need. There was nothing else available to learners that looked, sounded or felt like those final KH250 B5s and the firm knew it. They even went out in style by lettering the seat covers, almost waving two fingers at anyone who couldn’t grasp the appeal of a two-stroke triple. Not a bad way to end a hugely successful lineage!

Owner’s tale

By Sam Samways

This S1B was built in October 1973 and imported from America in 2013. I bought it in 2014 from a good friend, Dave Higgs, and it came with fresh green paint, a rebuilt top end and a set of his stainless expansion chambers. The chassis has never been painted. About five years ago, I decided for a change when a set of period Allspeeds came my way for half-sensible money. Soon after this, my painter contacted me to say that a full original red S3 paint set had come in to him to be repainted! A deal was done and I had a red option. I now tend to swap over each year from green to red, and this year its red!

Two years ago I fitted a pair of alloy rims after sourcing hubs from Triples Club members. The bike has been used every year and covered 6000 miles in those nine years, only requiring plugs, points, head gaskets and oil changes. Top tip for any of these S series triples is to get the timing spot-on – 2.6mm BTDC, set every year. If had to find any downside of this fun triple, it’s the front drum that can suffer when used a great deal on hot days. But overall, I love it and have become very attached to it.