One man’s purchase has turned out to be a classic discovery for potential Moto Guzzi owners – but most examples are much better! It’s all part of the fun of 1970s Italian cruiser ownership.

Words and photos by Oli Hulme

Italian motorcycles had a legendary reputation in the 1970s. They were stylish, they were fast, they were powerful. They were also hopelessly unreliable and would dissolve if exposed to the open air. Their electrical systems would fry on a whim and the paint and chrome would fall off in lumps.

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

And it wasn’t just the British climate that would inflict such damage. In a 1975 road test of a Moto Guzzi T3 California, French magazine Moto Revue said its eight-month-old test bike had peeling paint, pitted chrome and rusty exhausts, and though the reviewer liked the result of the cast iron Brembo discs going rusty and becoming a “beautiful flamboyant red”, the writer concluded: “You will agree that our Italian girl looked rather bad. And yet, she had slept very little under the stars.”

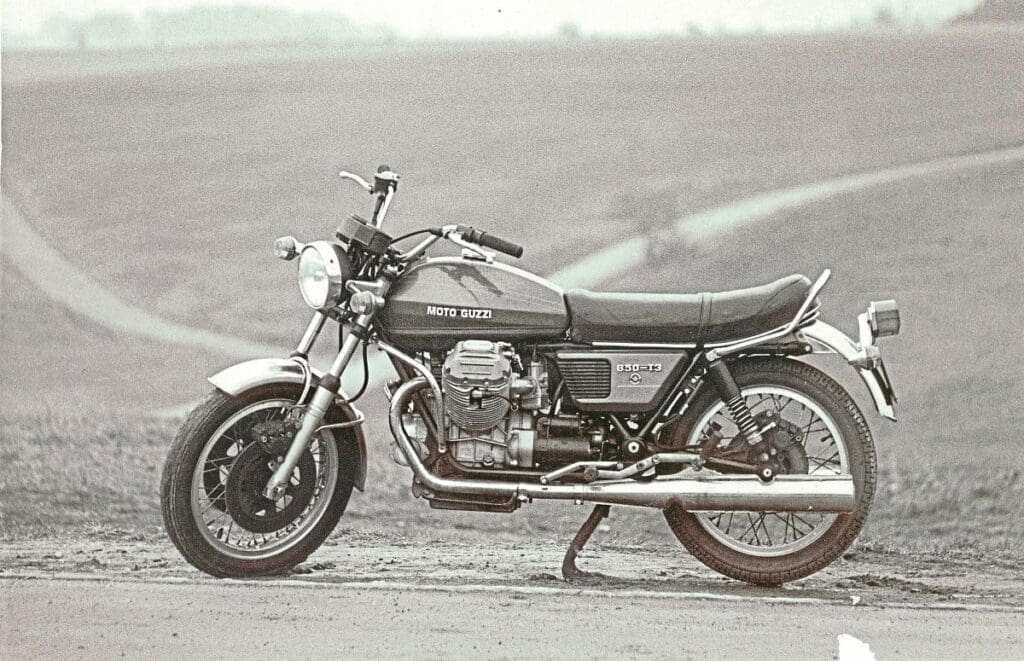

And yet, sometimes things last longer than expected. This is Paul’s 1978 Moto Guzzi 850 T3 California. A UK-registered bike with previous owners’ records going back to 1986, he bought it in December 2021. And the thing about it is, well… just take a look at the speedometer, which reads 92,347 miles, achieved by a motorcycle that should have rotted away four decades ago, if you believe the legend.

Paul’s California hasn’t always looked like this. It probably did when it rolled out of the showroom in 1978, but the years were not kind. When he picked his 850 up that December, it was “a bit of a state”. He took it on a 40-mile round trip: “Returning from the ride, the right-hand cylinder stopped firing, but it still kept going. I put it down to dirty fuel. All my Guzzis have additional fuel filters. The tank’s not rusty inside, it was just an accumulation of crap.” When Paul got it home, he got to work.

The electrics were a mess and so was the frame paint. The previous owner had coated it with diesel as a rust preventative, meaning the whole bike was covered in a thick coating of old diesel, mud and other road muck. “It was running,” said Paul, “and despite the diesel and mud coating, the frame was extra rusty. It looked like it had lived in a pond.” The thing to do, he thought, was take it all apart and start again.

“I decided to strip the bike completely and take the frame down to bare metal, de-rust and then respray it with two-pack black from rattle cans, which I did in the back garden on warm days over the summer.

“After stripping it down, I found that almost everything was rusty, from the headlight brackets to the breather pipes. The swingarm pivot bearings were seized. I think at this point the most important tool I owned was a sturdy workbench. I had to use a blind puller from Amazon with a slide hammer to free the pivot bearings and the workbench was jumping into the air while I was doing it. It took the whole of Christmas to get it out, which gave me something to do.”

Once the swingarm was out and refurbished and the frame and brackets repainted, it was time to start putting it back together. There were new YSS shocks, and the forks were rebuilt with new springs – though the first set of springs fitted were too soft and the forks needed a second rebuild to add some stiffer items. The master cylinder for Moto Guzzi’s linked braking system needed to be changed and the front cylinder refurbished too. Both Brembo calipers needed to be changed because the nipples (two to a caliper, one for each piston) had seized and they were swapped for later calipers with single nipples. The original braided brake hoses were good and are still in use. The big Moto Guzzi original airbox was swapped for a pair of smaller pod filters, which take up much less room.

With the bike back together, it was time to take a closer look at the electrical system. It was a bit of a mess – “someone had done some bodged up mods,” said Paul. He also found two wires broken in the loom. “I fixed those and went for a ride, when the indicators, stop light and horn stopped working. So, I decided to fit a new loom.” The new loom has been meticulously marked and tabbed with small labels to make any future fault-finding much easier.

Some bits were beyond rescue. British bike fans might notice that the rear indicators are Lucas items, which are close in design to the CEV originals. A screen that came with the bike was binned in favour of a lovely, clear, new-old-stock original. The seat too was replaced as the previous item had rotted out – but the old cover was good, and Paul managed to sell the seat on to another California owner for them to restore. Crash bars and panniers are original. The exhaust down pipes and silencers are stainless steel, but the balance pipes between them were steel and had gone rusty, so they needed replacing. And while the electrical system was a mess, the original points ignition system is still in place: “Everything works, so why change it?”

The paint on the tank and side panels is as Paul got it, as are the lovely Borrani rims. There are lots of new nuts and bolts, but the engine appears to be untouched and has the original, polished rocker covers.

An unfortunate incident occurred when a young lady in a small hatchback rear-ended Paul’s Guzzi. This required a small repair to a bent indicator bracket and a cracked taillight, which fortunately are still available new.

Operating the centrestand is a little challenging, but the sidestand is of Guzzi’s superb locking design, avowing the danger common with many an Italian bike that it will snap upwards without giving notice, sending many a Ducati crashing to the ground.

The dreadful left-hand switchgear which blighted many a Moto Guzzi in the 1970s has been replaced by something a little less clunky and less liable to fail. The original footboards are really comfortable, though the heel-toe gear change took a little while to get used to.

The California is a solid and easy performer, the ride superb, and the handling is good enough to ground the centrestand tine. For a bike pushing 100,000 miles, Paul’s California looks ready to head off on another four global circumnavigations, in the style only a Moto Guzzi can provide.

Fifty years on the road

The California has the honour of being the longest-lasting model in Moto Guzzi’s 102-year history. Launched in 1971, there was a California in the catalogue until just a few years ago, though obviously in different guises. Launched to take on Harley-Davidson’s Electra Glide, the California gained fans the world over.

The journey to California

Back in the late 1960s, American police forces were falling out of love with their aging Harley-Davidson twins, and when Moto Guzzi bored its new shaft-driven electric start V-twin out to 754cc, it was adopted by several police forces, including the influential LAPD, which did its reputation among US civilian buyers no harm at all. These Moto Guzzis were big motorcycles with plenty of presence, and the engine was carried low in a tubular double-cradle ‘loop’ frame (denoting the loop at the rear of the subframe behind the seat), with fat tyres providing good grip in the curves. California was the name given to a version of a bigger 850 civilian model launched with transatlantic styling in 1971 – a bold move by Guzzi.

The Tonti frame

In 1971, designer Lino Tonti came up with new frame around a stiff spine. Importantly, it had a removable lower left frame rail, which made it much easier to get the engine out. While the engine was pretty solid, being able to remove the gearbox and clutch more easily was a must. Having said that, it was still a job that took six or seven hours.

The Tonti frame, as it became known, was first used on the wonderous V7 Sport launched in 1971 that, along with a completely new frame, had an evolution of the V-twin engine. This good-looking machine, the V7 750, with its elegant lines and exceptional stability, was an extraordinary success. Bravely ditching the kick-start, Moto Guzzi was the first manufacturer to do this. Uniquely, Moto Guzzi fitted a linked braking system to its bikes; this involved one disc on the front being operated by the handlebar lever, the other and the back brake disc were operated by a foot pedal. While the single disc wasn’t really up to the job on its own, when combined with the rear pedal it was extremely effective.

The shaft drive was incorporated into the swingarm, with the pivot on the rear frame down tubes.

The big block engine started off with round barrels, but these later had square finning, and the terrible switchgear was dumped in favour of better, Japanese-styled offerings.

Tonti goes stateside

There were a number of big Moto Guzzi tourers that used the new frame, starting with the 850 T, which was followed by the 850 T3.

The 850 T3 California launched in 1975 and was an instant hit. Interestingly, the style of the California was popular with many European buyers too, the bike being more stylish than BMW’s big twins. The California’ thunder was stolen slightly by the launch at the same time of the automatic gearbox equipped V1000 Convert and in 1978 by the more refined 1000 SP Spada, which was clearly aimed at knocking a few more lumps off BMW’s touring market share.

A California didn’t cost a lot to live with. The oil needed changing every 3000 miles or so (a job that took the average home mechanic a couple of hours), while servicing took place at 7000 miles. Fuel consumption was not heavy, while power varied between 55bhp and 63bhp, depending on who was measuring it. The engine featured a big car-type electric starter, which didn’t spin things fast, but with a well-charged battery it would comfortably heave the two pistons over, if a little slowly. When the button was pushed, the bike rocked dramatically from side to side before firing. The rider just needed to get it into gear, with a clunk familiar to Guzzi owners, take it up to 2500rpm and roll away. The big screen improved long-distance travel but did it at the expense of a reduced top speed, lazier handling, and increased fuel consumption. If you wanted more speed, you would buy a Le Mans. It made a delicious rumble, and the linked brakes were wonderful things. From the late 1970s, there were 15 different California models. These were the California II, California III, California 1100, California Jackal, California EV, California EV Touring, California Aluminium, California Titanium, California Special, California Special Sport, California Stone-Metal, California Stone-Touring, California Classic, California Touring, and California Vintage models. These bikes, part of a line that lasted well into the 21st century, were very popular in the US and Italy. They got bigger and fatter and gaudier as they headed for 1400cc and while the West Coast styling didn’t catch on with everyone, many rated the later California models highly for their long legs and easy charm.

In 2019, the big engine that powered the last California Touring was discontinued, though models remained on sale for a while. Since then, Moto Guzzi has concentrated on the ‘small block’ V7 and the new V100 Mandello engine. But the demand for a big V-twin tourer surely remains and US West Coast branding could easily return one day.

SPECIFICATION (1977 California)

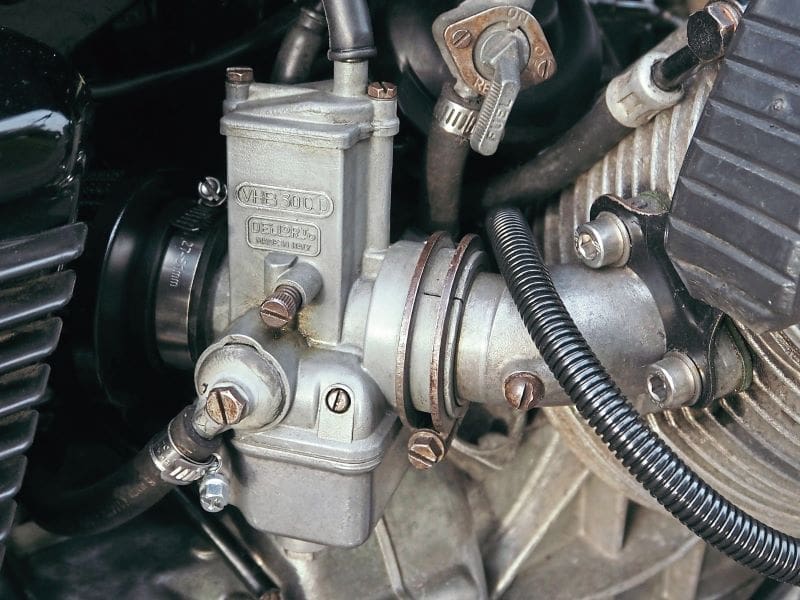

ENGINE: Ohv twin DISPLACEMENT: 844cc BORE x STROKE: 83x78mm COMPRESSION RATIO: 9.2:1 POWER: 68bhp FUEL SYSTEM: Twin 29mm Dell Orto CLUTCH: Dry twin plate GEARBOX: Five-speed LUBRICATION: Wet sump FRAME: Duplex tubular FRONT SUSPENSION: Telescopic forks REAR SUSPENSION: Twin oil-damped shocks WHEELBASE: 57.9in (1470mm) SEAT HEIGHT: 31in (787mm) DRY WEIGHT: 494lb (225kg) FUEL CAPACITY: 5.3 gallons (24 litres) TYRES: 3.50×18/4.10×18 front and rear BRAKES: 2x 300mm discs front, one 242mm disc rear (linked) ELECTRICAL SYSTEM 12v TOP SPEED: 120mph

OWNERS’ CLUB

Moto Guzzi Owners’ Club

motoguzziclub.co.uk

SPECIALISTS

Gutsibits

gutsibits.co.uk

Made in Italy Motorcycles

madeinitalymotorcycles.com

Stein-Dinse

stein-dinse.biz