There never had been a motorcycle so packed with original design and high speed stamina. Old legends like this, says Dave Minton, never die. They simply race away…

Vincents in the post-WW2 period were as mythical as they were rare. The two went hand-in-hand of course. As schoolboys we relished the myths, repeating them amongst ourselves until they had become a vital matrix in our scatty lives. We knew of Spitfires that had broken the sound barrier, Rolls Royces that had covered a million miles with their bonnets sealed, big game hunters who despatched elephants with rim-fire 0.22s, Egyptian pharaohs revived after 5000 years of sealed mummification.

And there were Vincents. ‘There was this bloke on holiday in America on his Black Shadow,’ we whispered. ‘The American military was testing some top secret radar and saw a thing too low for a jet plane and too fast even for a racing car. When they stopped it at a road block it was this English bloke on his Black Shadow doing’ — and then we’d gasp in admiration of our ever-increasing temerity — ‘over 200mph! They took it away to test it and he never saw it again…’

And with utter conviction we believed, without the slightest attempt at consensus with the former; ‘No one’s ever got a Black Lightning into top gear because it’s so fast that if you did your lungs would explode!’

You get the picture? Vincents were not simply fast motorcycles; they were the nutritious juice of national myth and magic and we thrived on the stuff. Now, while it must be apparent that the material qualities of these big black V-twins are unlikely to match schoolboy dreams, they remain one of the most remarkable motorcycles ever built..

Why? Three things.

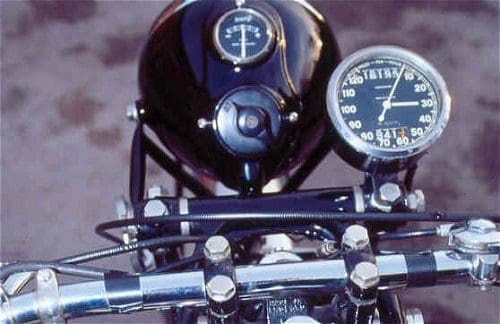

1). Phil C Vincent, who founded the company in the mid-1920s, was a sometimes obsessive idealistic engineer who, never the less, had a twinkle in his eye. His emplacement of his sport’s model 150mph speedometer upright and in blank denial of the then 100mph bulls-eye import was nothing more or less than inspired showmanship. As was the machine’s all black livery in an age otherwise mesmerised by glitter. Such understatement was proof of righteousness.

2). PCV’s insistence on competent rear suspension, when almost without exception all others seem struck witless by the need.

3). The Vincent company hired a development engineer in the mid-1930s whose name was to ring around the world of motorcycling: no less than Guilio Carcano of Guzzi. And, for equally valid reason, the great Phil Irving, a uniquely creative Australian whose laconic pragmatism offset PCV’s intensity.

Let’s deal with first things first. Keep firmly to mind that even the most ethereal legends must at some time have had something of substance between them. The Vincent V-twin’s lay in PCV and Irving’s scientific approach to design. Without space to explain it all (there are plenty of books on the subject), on e example will have to suffice.

When in 1934 Vincent launched its first in-house engine, the 26bhp @ 5300rpm, 499cc Meteor single, it was witness to the company’s despair at then weakness of proprietary engine manufacturers’ products at high speed. Most of the problems were valve originated. The mysteries of the combustion process had at last been over-effectively revealed.

By observation and calculation the two Phils became convinced that valve failure was more a consequence of lateral vibration than of unsatisfactory metallurgy. To this end the new engine sported upper and lower valve guides. Without a centre section the valve lacked a fulcrum. And into the empty central section they placed a forked rocker pressed onto a shouldered valve stem. This largely eliminated the rocking action of the conventional top-end rocker. Vincent top ends stayed together.

PCV also rejected the popular long-stroke engine, which had been retained mainly to provide the high induction speeds necessary for low engine speed torque rather than high-revving, valve-wrecking bhp. It will be appreciated that for any given rpm, the distance travelled by a long stroke engine’s piston must be greater than that of a short stroke. There fore the higher the piston speed, the greater the inertia forces must be during reciprocation, and the greater the mass of the increasingly robust components must be to resist them. Moreover, the bigger bore of a short-stroke engine allows much greater choice of valve angles and sizes for improved breathing.

When, therefore, PCV decided on understatement as the style of the Black Shadow, it was with all the confidence of an engineer with implicit faith in his machine’s ultra-sound engineering foundations. It looked good because it was good.

Point number two. Can rear suspension be that important? If ever a radical newcomer upset a traditional icon it was during Brooklands’ final magic years when Vincent began taking speed records from Brough Superior. Brooklands was a track so rough that sheer courage was as much a part of the rider’s armoury as skill.

Several years ago now in the late 1990s I met one of motorcycling’s gentlemen, Jim Kentish. Tall, quiet, self-effacing, yet as alert as a cat, with some prompting Jim admitted to being a Brooklands’ Gold Star holder, awarded to ton-plus lappers. In 1937 Jim bought an early Series A Rapide and one summer’s Saturday he took the afternoon off and rode from the West London theatre, which he managed, to Brooklands. He not only won a Gold but was offered Dunlop sponsorship on the spot. The he rode the Rap back for his evening stint at the theatre.

Manifestly, Jim was a formidable young man (he still was when I met him!), but the contribution of his Vincent needs consideration too. Remember that it was a wholly road-equipped, standard, non-race-tuned sport-tourer with a top whack of 107mph or so, which signifies that Jim was circulating as near as dammit to flat out. (A year later, Vincent development rider George Brown, on what must have been a blue-printed standard Rap, recorded a lap of 106mph and a top speed of 112.8mph).

Getting facts out of Jim, an over-modest individual indeed, was like picking winkles from their shell with a blunt thumb, but I did learn that the Dunlop representative was impressed more by the Rapide’s roadholding than anything else. And that was when Vincents still relied on Brampton girders up front.

The technical origins of the Rap have become almost as famous as the engine itself: how one lunchtime in 1936 Irving noticed two overlapping Meteor engine blueprints in attractive radius, and how quite literally a few weeks later the big twin appeared. What is less well known is that PCV was hard-pressed by previously loyal Bruff-Sup devotee Eric Fernihough for a Brooklands racer. Fernihough had been impressed by the Meteor’s performance and stamina but PCV was all too aware of the limitations of a 500 single.

Irving’s V-twin revelation must have come like a gift from the gods, hence its hurried materialism. And Irving, ever the wry pragmatist, adopted a 47.5-degree throw simply to shoe-horn it into Fernihough’s existing frame.

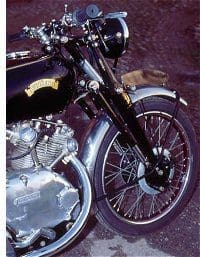

In 1949 Vincent offered to a stunned world its classic model, the Series C Black Shadow, a greatly improved motorcycle. It crankshaft had been thrown from the Series A angle to a more rounded 50-degrees mainly to ease magneto sparking; its lubrication was improved; its breathing eased and, most obviously, it was equipped with the famous Gridraulic front fork and had no frame.

Experience with the Series A frame had convinced PCV especially that frames were best avoided. So the two Phils bolted the steering head to the front cylinder head, connected it to the rear head with a box-section oil tank, hung the swinging fork (or arm, if you must) on gearbox plates and butted the rear suspension units against the rear head. Weighing 490lb fully equipped, the C was not merely light but also offered unprecedented torsional stiffness.

With 55bhp (horses were different then) on tap at 5700rpm. The Shadow was fast, very fast, and road tested at over 125mph by race-leathered prone testers. With 115mph available on tap to a bloke tramping up the Great North Road in a flat cap and bulky Belstaff Supersenior coat, there was nothing to touch it by miles. Jag XK120? Hardly. The world and his wife went ga-ga. No one, not even the most cynical journalists, expressed themselves other than through paens of praise as they discovered previously unknown dimensions of usable speed.

Perfect motorcycles, then? Nope. They rattled like skeletons in a royal cupboard, mainly as a consequence of too many bits and bobs whirling around inside echoing aluminium caverns. Their centrifugal clutches defeated DIY mechanics of traditional bent (and many of the modern day, too), although when adjusted correctly with original parts they performed admirably for a lifetime. And their hydraulic dampers, which were universally in their infancy anyway, were abominably beyond belief.

If they had one deplorable performance trait it was the C’s occasional and quite unpredictable penchant for a tank-slapper. No, not the speed wobble or shimmy which is now described as a tank-slapper as a means of magnifying the harmless experience, but the real, unavoidably terminal, thing. Invariably at three figure speeds without prior signal the forks would clash explosively from lock-stop to lock-stop, with the inevitable result… Why? We did not know then (it happened to me in 1964) but the cause has been traced to a mixture of steering train slop from worn fork bushes reacting to a rear end pitch from inadequate damping.

Why not tele-forks? Because PCV and Irving both despised the lateral flexure then unavoidable with the forks during braking and cornering. Overlooked now, their new fork had to accommodate the enormous stresses of sidecarring. In action, the Girdraulic, with its twin spring boxes and single central damper, remained under stress more faithful to its blueprint than any tele or orthodox girder. Besides, it was extremely handsome and terrifically enhanced the already rangy appearance of its all-black bearer.

Why not tele-forks? Because PCV and Irving both despised the lateral flexure then unavoidable with the forks during braking and cornering. Overlooked now, their new fork had to accommodate the enormous stresses of sidecarring. In action, the Girdraulic, with its twin spring boxes and single central damper, remained under stress more faithful to its blueprint than any tele or orthodox girder. Besides, it was extremely handsome and terrifically enhanced the already rangy appearance of its all-black bearer.

A year before the factory closed in 1955, it produced the enclosed (NOT ‘streamlined’) range of Black Knight and Black Prince. Dave Danielson, one of the Vincent Owners’ Club’s stalwarts, with a display of courage far, far beyond the call of duty, loaned me his precious Black Knight for a run through Wales. In common with many current big Vins, Dave’s had been modernised to cope with today’s traffic, enhanced by such niceties as a powerful 12-volt alternator, borrowed from a Citroen 2CV, electronic ignition, modern dampers, stiffened brake plates and so on. A classicist without purism, Dave, an experienced and very professional car mechanic, used his model regularly hard and fast, including annual overseas holidays/ Breakdowns? In 30 years his Knight has broken down once only, and that was when a low tension wire parted.

Starting a Vin is best done after easing it over compression, so flywheel inertia rather than you leg bumps compression into ignition. You never forget it. Bottom gear clicked comfortingly into engagement and the clutch, light and controllable, took up much like a diaphragm unit. Although the steering was weighty thank to a 4/4.5-inch trail, the overall impression was of a light, compact machine which in second gear alone ambled along from tickover speeds to city traffic bursts. Idling was a rumbling heart-beat bass chuckle.

Mighty sinews catapulted us to 80mph faster than most modern traffic could manage. Dave assured me that with the increased oil tank capacity he has engineered, he has on occasion cruised at three figure speeds, two up, for long periods. In view of the relaxed, high geared, easy gait of the machine, it’s wholly believable. These things pull a high top gear, which at 3.5:1 means a mere 3000rpm at 66mph, rising to 4500 at 100. It’s geared for a theoretical 117mph, 5300rpm, maximum.

The day was a blustery one and I could feel the bike responding, but lightly, without disturbance which, considering the empirical method of development (no wind tunnel save that resulting from a development rider’s bold right wrist) is astonishing. It was no good trying to hustle the Knight in a modern, forceful style: on those winding Welsh mountain roads I found it much preferred a rhythmic, fluid style, which it met by sailing handsomely — and much faster on the speedometer than I judged — through the curves.

For myself, I revelled in two things — the Knight’s full-blooded snarl as I cracked on through deep valleys, against which Dukes sound woolly and Harleys grossly flatulent. Ah, the joy of hearing iron and alloy at full gallop under gaping throttle. It wasn’t a nice noise at all. Just a rasping cough of a big British twin in full cry and devil take the hindermost.

The other was the pleasure of pedigree. This was powerful history on two wheels and I was part of it. The rewards of such pleasures may be personal, subtle and open to debate but they are nontheless real for all that.

When this bike was new it had no rival. To a modern rider it might look strange. He would be appalled by what he would perceive to be a vibratory power delivery; slow yet flighty steering; harsh suspension; puny brakes and ‘impossible’ starting. A modern rider would also be fascinated by the sheer indolence of the high-geared, low-revving, long-legged, big-mileage pace. He would love its aristocratic, commanding riding position. He would find its wind and weather protection uncanny. He would marvel at the multitude of ownership and rider qualities, the magnitude of engineering excellence, the lavish design detail which makes it possible to tailor the bike, with barely any tools, to suit you personally.

Did it actually vibrate? No, far from it. But this is how the ‘life’ of a living engine is described now. After a day in the saddle of the Knight, our modern superbike rider may well wonder where his racing egg whisk’s vitality had gone…

Photos by kind permission of Simon Everett

Vincents. Myth or machine?