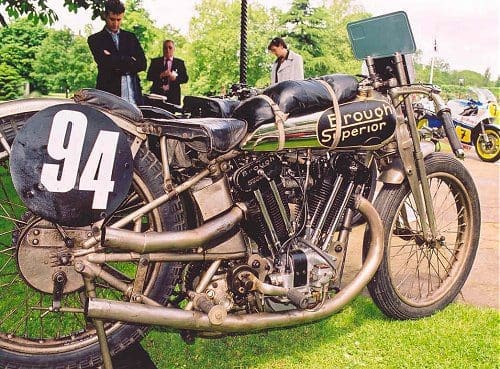

In 1919 George Brough arrived on the motorcycle scene and brought with him his Brough Superiors. By sweeping up more records on beaches, speedbowls and strips (Norton won the road races) than seemed plausible, these British V-twins roundly convinced the British, at least, that they could not be beat. And so a legend, a handsomely presented legend at that, was born.

The first three years of Brough Superior were more or less gestatory, but then in 1922 the first of the famous models, the sidevalve SS80, was born. It pedigree was all that was required of a blue-blooded Gran Turismo. It even participated in the 1922 ACU Six Days Trial (which matured into the ISDT). George Brough himself, while an unparalleled stylist and publicist, also managed a brave right fist. As a means of proving his new model’s power and speed, as much for his own satisfaction as potential buyers’, he sprinted and hill-climbed the SS80. And he raced it at Brooklands, managing an unofficial 100mph lap on one occasion.

During 1922 GB and his SS80 stormed to success, as little had before save perhaps Scott prior to the Great War. Brough achieved FTD at 51 successive sprints and hill-climbs, often shockingly surfaced and winding, which vied with infant road-racing for prestige. The end came on the 52nd occasion, when man and machine crossed Clipstone’s finishing line independently, the seat of GB’s breeches taking most of the punishment following a front tyre blow-out at full chat.

During 1922 GB and his SS80 stormed to success, as little had before save perhaps Scott prior to the Great War. Brough achieved FTD at 51 successive sprints and hill-climbs, often shockingly surfaced and winding, which vied with infant road-racing for prestige. The end came on the 52nd occasion, when man and machine crossed Clipstone’s finishing line independently, the seat of GB’s breeches taking most of the punishment following a front tyre blow-out at full chat.

By this time fame of GB’s big twin had won it the compliment of a nationally famous nickname, ‘Old Bill’. It had been borrowed from a Great War cartoon soldier of utterly indomitable, if somewhat fundamental, nature. Maybe it was this which convinced GB that fortune would be most likely to follow fame…

Because George Brough’s talent for his product’s aggrandisement has become as legendary as the motorcycles themselves, there’s a danger of the former ousting the latter. In fact GB, while no formally trained engineer, knew what was what mechanically. Before very long Old Bill had been equipped with ancillary stays triangulated through two dimensions (length and breadth) between the rear subframe and the main frame. In all production Brough Superiors this ugly lattice was, of course, dropped in favour of a more orthodox frame, although one braced by a wide-spaced, duplex engine cradle. The excellence of its high speed qualities may be judged by its use on the more powerful ohv SS100 of 1925.

Brough Superiors certainly handled well, even over Brooklands’ notorious bumps, and they were reliable. They were reliable because GB himself insisted upon the very highest standards of what we now term build quality from his engine suppliers. The motors were manufactured to hand selected component assembly standards, rather than the normal first-come-first-fitted method. Meticulous attention was paid to engine balance, crankshaft assembly, valve timing, porting, pistons and bores, carburation and ignition – ‘blue-printing’, we would call it.

When GB felt that JAP was no longer able to meet his demanding standards in 1932 he turned to Matchless, which continued supplying SS80 and SS100 engines up to 1939 when, for all practical purposes, Brough Superior production ceased. When an SS80 left the factory it did so accompanied by a personally GB-certified 80mph top speed. In 1923 that was very, very fast. To achieve this each engine had to be capable of at least 30bhp as measured on a Heenan and Froud dynamometer.

When GB felt that JAP was no longer able to meet his demanding standards in 1932 he turned to Matchless, which continued supplying SS80 and SS100 engines up to 1939 when, for all practical purposes, Brough Superior production ceased. When an SS80 left the factory it did so accompanied by a personally GB-certified 80mph top speed. In 1923 that was very, very fast. To achieve this each engine had to be capable of at least 30bhp as measured on a Heenan and Froud dynamometer.

When I rode an SS80 in the late 1990s, it was owned by one Jess Bamford. He handled it without reverence but with respect – slinging it around a 180-degree turn in the yard and booming out onto the main road in a fast, accelerating curve to join the dual-carriageway traffic. The SS80 looked mile worn yet superbly competent, and it sounded solid as its owner hustled it up the road leaving nothing but the black velvet rip of a side valve twin clambering into a wide throttle.

And then – my turn. The SS80 felt sharp, quick and alert; a sporting machine and not much of a cruiser. A couple of priming pumps on the valve lifter helped starting. The Brough Superior’s Matchless engine responded quickly to throttle movement but the modified Norton Inter gearbox involved plenty of movement – more like thigh rather than mere ankle action. The engine was tractable, however, so long as the ignition was used correctly. On some bikes of the period speed could be varied on the ignition alone but the SS80 was less than amenable to this and spat and cracked in protest, but when its ignition was retarded in top gear the engine would idle along at a miraculously low walking pace.

Acceleration was rapid; probably a reflection of the race-bred, well-spaced four-speed foot change gear cluster, rather than of actual engine power. I stopped accelerating the SS80 at 70mph, and its cruising speed was around 65mph, but its owner treated it hard and 80mph came up regularly. He’d owned it since the early 1990s, having found it unwanted in a corner of a Coventry classic car showroom. The clock showed 32,000 miles but Bamford had spoken to its previous owner and knew it had been round at least once.

This machine did not produce any vibration truly worthy of the name. While commendable, it is also a reflection of the rpm limitations imposed by side valves. Their gas passages are sufficiently convoluted and their combustion chambers so restricted as to limit engine speed to little more than 5000rpm. As a consequence side valve engine tuners are forced to search what are normally regarded as the mid-speed ranges for extra power.

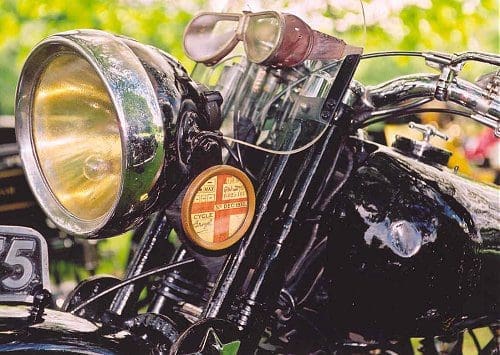

One of the great identifying features of a Brough Superior is its Castle leading link front forks. Jess Bamford’s SS80 had Druid girders because by the time his 1937 model was in production, Brough Superior was offering them as an option on the less expensive SS80 Special model (£95 compared to the De Luxe version’s £110, plus tax). Some say with a guarded whisper that the girders also perform better under duress. I’d hate to put it to the test but have found no worthwhile fault with the Castle-forked Brough Superiors I have ridden over the years.

What did become plain was that Druid girder front forks and Bentley and Draper triangulated swinging fork rear suspension made the SS80 undeniably shock absorbing and tenacious over bad roads. Unfortunately, GB’s clientele (nothing so coarse as mere customers!) demanded pillion passenger comfort, too, and the B&D rear end offered loved-ones behind little but unloved and bruised behinds. So Brough went the rear plunger route. A shame, but pivoted fork systems work reliably at high speed only when hydraulically damped.

What did become plain was that Druid girder front forks and Bentley and Draper triangulated swinging fork rear suspension made the SS80 undeniably shock absorbing and tenacious over bad roads. Unfortunately, GB’s clientele (nothing so coarse as mere customers!) demanded pillion passenger comfort, too, and the B&D rear end offered loved-ones behind little but unloved and bruised behinds. So Brough went the rear plunger route. A shame, but pivoted fork systems work reliably at high speed only when hydraulically damped.

George Brough put great store in appearances, hence on of the most charismatic large capacity petrol tanks ever to grace a motorcycle. Its exaggerated dimensions foiled sheet steel forming methods so completely that the tank had to be assembled from carefully soldered strips. This had the triple weakness of defeating reliability for endurance speed events, chromium plating and reasonable production costs. Jess Bamford’s tank was one of a small handful made out of welded sheet steel by a master metal worker to the Brough Superior club’s specification.By the time the SS80 should have reached its peak of popularity, Britain was losing interest in flat-heads. Nothing they did could not be bettered in every respect by ohv engines. A decent ohv 500cc single could thus compete in terms of speed with a 1000cc sidevalve twin, as well as out-braking it and out-cornering it. European motorcyclists and the British in particular were powerfully influenced by road-racing.

So in retrospect it was inevitable that within two years of the SS80’s appearance it would be surpassed in all respects by the SS100, a 20mph faster ohv V-twin of such majestic bearing it might have originated from a naval architect’s drawing board. The glory that should by right of progeniture been the SS80’s passed to the more strapping younger son, the SS100. To it went all the prizes.

The SS80, though, provided George Brough’s bread-and-butter, selling 1084 machines in its nine year life, compared to a mere 383 of the lordly SS100s at their extravagant price of £170. Today the SS80 remains an affordable option – if you want a Brough Superior but have less than a five-figure sum to spend, then an SS80 could provide a passport to an extremely exclusive association of riders.

Classic and British bikes like this one appear every month in the pages of RealClassic magazine. Our in-depth articles by expert and enthusiast authors reflect the old bikes we buy and ride in the real world: frequently fabulous; occasionally awful, but always interesting…