Think of the days of export guarantees when America reached for its wallet and bought the T120 by the boatload. Britain was proud and Triumph was on top of the world … and just because of the Oh-my-goodness of it all Bonneville, which so influenced the path of motorcycle manufacturing, for a not inconsiderable period, that the poor old T150 Trident had to be tarted up to look like one (lest the lads spurn it in favour of their traditionally dressed and best-beloved Bonnie) and echoes of its styling cues resound around the Hinckley Thunderbird to this day.

The Bonneville – an historic icon? Certainly, if sales statistics, the journals of record, and the legends passed through generations are anything to go by. John Nelson, of Triumph’s development team and then that company’s World Service Manager, believes that from 1964 to 1969 the Bonneville ‘was the ultimate ideal of every young motorcyclist’ and even our own (usually somewhat more inclined toward BSA) Steve Wilson remarks that ‘the 650s of the 60s really were the legends, where the street could meet the elite…’Today however, it could be a very different story. The Bonneville might’ve been a world-beater back in the Swinging Sixties but how does it compete 30 years later, in a world brim-full of motorcycle idols both old and new? Performance-wise the words ‘hopelessly’ and ‘outclassed’ spring instantly to mind, but the same could be said of anything over three years old when ranked against the current crop, so this is hardly a fair criteria.

A motorcycle legend really shouldn’t be restricted by its physical limitations though – it should rise above them, somehow. And for me, an iconic motorbike has to do more than just sit there and look pretty. Baby lambs, beautiful pictures and fine summer days fulfill that capacity for me, thank you; motorcycles, however legendary, have to manage a few basic functions as well. Like starting OK, stopping OK, and going a bit (especially round corners) in-between. And … it has to do the looking pretty thing, too. So it was that I took possession of this Bonneville, to see if the whole experience really is greater than the sum of those parts.

A motorcycle legend really shouldn’t be restricted by its physical limitations though – it should rise above them, somehow. And for me, an iconic motorbike has to do more than just sit there and look pretty. Baby lambs, beautiful pictures and fine summer days fulfill that capacity for me, thank you; motorcycles, however legendary, have to manage a few basic functions as well. Like starting OK, stopping OK, and going a bit (especially round corners) in-between. And … it has to do the looking pretty thing, too. So it was that I took possession of this Bonneville, to see if the whole experience really is greater than the sum of those parts.

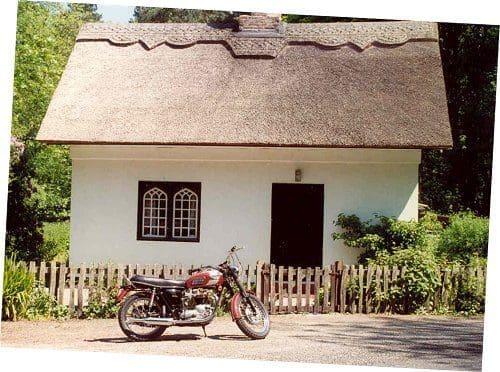

‘Remember not to over-rev it. Change up early – real early’. Proud Owner plainly had a bad case of Roadtester Nervosa. Perhaps my bungee-hooking the camera kit to the back of the bike with gay abandon hadn’t helped his confidence? I smiled in a reassuring manner (I hope; but then who can tell what it looked like from the other side of a full-face crash helmet) and bounced onto my Bonnie-for-a-day, a 1970 T120R, supposedly the last of the good ‘uns, resplendent in astral red (ish) and silver. It surprised me by being little – but all older bikes surprise me by being little in comparison to their hulking modern cousins. Somehow though, I’d built the Bonnie up in my mind as being of a far greater stature and was charmed to find that this US version eased up from the sidestand to a very manageable height (no doubt this T120’s slim midriff helps). All good impressions thus far, then.

So much for sitting on it – starting was bound to be harder. Past experience has shown that the more desirable a machine is, the more quirks and foibles it has tucked up its pipe. And starting is where every motorbike loves to demonstrate just who’s boss… Expecting a struggle, and wishing that the assembled crowd of mechanics, browsers and (naturally) Proud Owner would kindly dematerialise – this instant – and leave a girl alone to get on with it, I tweaked ticklers and tugged levers with what might have been a semblance of confidence. I cheerily swung my hoof downward in the hope that lots of enthusiasm would make up for a lack of technique. And blow me down if it didn’t start. First time.

I acted nonchalant, sorted my feet out so’s not to attempt a gear change with the brake pedal and rumbled away from the crowd. Apart from a moment’s panic about when to swap cogs (‘is 10mph too fast for first gear?’) we managed it fairly gracefully, Bonnie and me, and the machine burbled up in my estimation. On the last gloriously sunny day of autumn we headed out onto the Cheshire highway, looking for adventure, looking for a good time, hoping to find a legend along the way. First things first, however; fuel.

And with peculiar appropriateness we pulled into an attendant-service only filling station that appeared to have been left over from the war (which one, I’m not sure), complete with quaint old fashioned dial-display pumps and a uniformed chap on hand to man them. We topped up on red stuff (lead replacement – I remembered!) and spent the next 15 minutes re-living the youth of the pump attendant who’d ridden motorcycles as a lad; always fancied a Bonneville, what a beautiful one that was, out for a spin, was I? An icon? Certainly he thought so.

And with peculiar appropriateness we pulled into an attendant-service only filling station that appeared to have been left over from the war (which one, I’m not sure), complete with quaint old fashioned dial-display pumps and a uniformed chap on hand to man them. We topped up on red stuff (lead replacement – I remembered!) and spent the next 15 minutes re-living the youth of the pump attendant who’d ridden motorcycles as a lad; always fancied a Bonneville, what a beautiful one that was, out for a spin, was I? An icon? Certainly he thought so.

I just thought it was a bit hot to be sitting in the midday sun, chatting away while my leathers re-enacted Dante’s Inferno. Still, at least I’d left the lining out of Frank Thomas’ finest that morning, so I was only part-poached instead of completely broiled. We bid the petrol man a cheery farewell, I held my breath and did the boot thing, and the Bonnie burst into life once again. Amazing.

We departed, obliging our audience with far too much throttle and revelling in the ridiculously satisfying exhaust note that this minor abuse produced. Only by the time I had changed up thrice (and early, I might add) did I realise that the side effect to all these sound effects was an astonishing increase in velocity. Strewth. Perhaps all the World Land Speed Record stuff was true then; it was a tweaked 650 T-Bird on the Bonneville salt flats that provided the inspiration for the early twin carb version of the Tiger 110, and it was two T120 engines strapped together, Heath Robinson fashion, that provided the grunt for the later Gyronaut. Which held the record – at 264mph maximum – for a half dozen years until 1974.

Which was in no danger from us. Mind you, I do believe we’d neatly (and inadvertently, one hastens to add) exceeded the national speed limit for that particular stretch of single carriageway, and without any undue exertion. Such is the charm of this gradually-developed 46bhp motor – by 1969 all the kinks were very nearly straightened out and the reputed 120mph might even have been within reach of some hardy lightweight. Some hardy lightweight with good teeth, that is, for even the best of Bonnies has been known to vibrate a touch under pressure, especially if the timing slips or the carbs are unbalanced. In 1969 they could put a man on the moon – but make a Bonneville that didn’t buzz? Perhaps not.

It was irrelevant to us, anyway; we peeled off the main roads (‘Leisure Drive’ said the signpost, which sounded just right) and thrust became less of a concern as the lanes tightened and twisted ahead. And it was here for me that the Bonnie stopped being a mobile museum-piece and turned into a real live motorbike. The modern BMW I’d ridden up on earlier – an ace sprint, by the way – suddenly seemed like some huge heavy-horse in my memory, as the Bonnie trod lightly through unfamiliar territory. Where hours before the BMW would’ve taken up the whole road to leave me no choice of line, the T120, like some elegant dressage star (mane and tail plaited, ears pricked and trotting with high hooves – you get the picture) stepped forward with a delicate grace. The lane seemed to be a mile wide.

It was irrelevant to us, anyway; we peeled off the main roads (‘Leisure Drive’ said the signpost, which sounded just right) and thrust became less of a concern as the lanes tightened and twisted ahead. And it was here for me that the Bonnie stopped being a mobile museum-piece and turned into a real live motorbike. The modern BMW I’d ridden up on earlier – an ace sprint, by the way – suddenly seemed like some huge heavy-horse in my memory, as the Bonnie trod lightly through unfamiliar territory. Where hours before the BMW would’ve taken up the whole road to leave me no choice of line, the T120, like some elegant dressage star (mane and tail plaited, ears pricked and trotting with high hooves – you get the picture) stepped forward with a delicate grace. The lane seemed to be a mile wide.

Delicate, but not fragile, mind you. The Bonneville rode precisely, tugging hard at the reins from 3000rpm and really rolling at around four. Which was just enough, given the roads we were on and given the taut, almost tense suspension. Imagine bunched hindquarters at every stride, and you have a fair impression of this Bonnie’s ride. Not unpleasant – and certainly not unexciting, but quite enough to make a long day in the saddle feel very, erm, long.

A pause for pictures and then it was time to return to the stable at a more dignified pace. In a very short time the Bonnie had become remarkably easy for me to ride, and on the way back I was able to look around and enjoy the scenery. Blue skies, green fields, and the best view of all was straight ahead of me. Belonging to an earlier age, a simpler age, has its advantages. The rider’s perspective was delightfully uncluttered; just a simple pair of clocks and a great shining headlamp. No indicators, so no switchgear, no mirrors flapping around, no fluid reservoirs or idiot lamps, dials or digits – no clutter, in short.

Which was how I felt after handing back the key. Uncluttered. Refreshed. And impressed. A good day with a real live Bonneville – and almost all of my reactions were positive. Of course, if I was having one I’d want one that was slightly less polished, if I was having one it would need to be a proper working bike, maybe softer around the edges, a bit less highly strung than this immaculate example, if I was having one it would have to be an export model…

An icon? To everyone. To me? Ask me in ten years or so!

Classic and British bikes like this one appear every month in the pages of RealClassic magazine. Our in-depth articles by expert and enthusiast authors reflect the old bikes we buy and ride in the real world: frequently fabulous; occasionally awful, but always interesting…